THE HISTORY OF HUMANITY’S BLOODY WAR AGAINST THE MOSQUITO

1881

1900

1904

1939

1962

1972

1974

Early 1980s

1981

Late 2000s

2009

2011

2014

2016

Source: wired.com

Source: wired.com

Scientists have discovered a way to convert nuclear waste into radioactive black diamond batteries which last more than 5,000 years. Researchers at the University of Bristol have found a means of creating a battery capable of generating clean electricity for five millennia, or as long as human civilization has existed. Scientists found that by heating…

Anthropomorphic, or human-like, animals are often the protagonists of children’s books. But new research suggests parents who want their kids to pick up on a story’s moral lessons should choose books featuring humans, not animals. Researchers in Canada found four to six-year-olds were more likely to share with their peers after being read a story…

Microwave ovens have been the norm in US households for almost 50 years. If you’re under 40, you’re more likely to have grown up with a microwave than without a microwave. Ever since they were first introduced, microwaves have been a source of controversy. While manufacturers and retailers maintain that microwaves are completely safe, many…

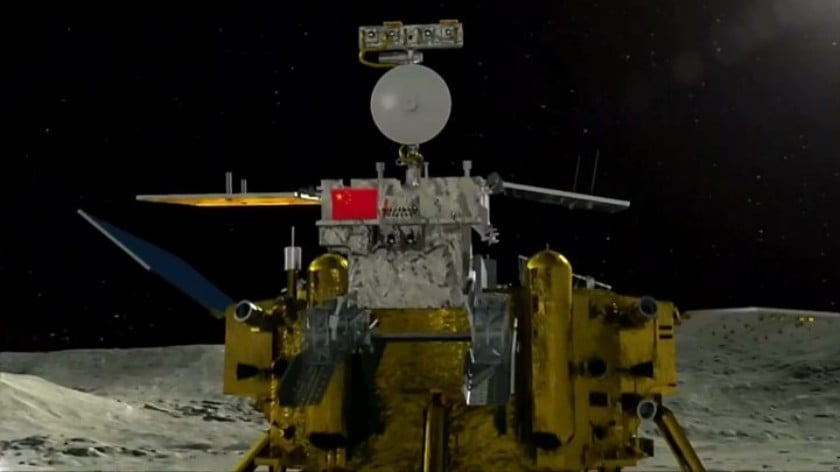

On the evening of January 2, a Chinese lander named for an ancient moon goddess touched down on the lunar far side, where no human or robot has ever ventured before. China’s Chang’e-4 mission launched toward the moonon December 7 and entered orbit around our cosmic companion on December 12. Now, the spacecraft has alighted onto the lunar…

Campi Flegrei is one of world’s most dangerous super volcanoes, and now scientists warn that it has reached critical phase and could erupt, which would mean apocalyptic consequences. A super volcano is defined as a volcano that is able to sling more than than 1,000 cubic kilometers of mass into the atmosphere. By comparison, one…

This article is going to be hard for some people to accept. Depending on what level of awareness you currently have and how far you have ventured into the rabbit-hole some of the information presented thus forward may be overwhelming and/or frightening some of the claims made may make you skeptical of the truth, again…