Syria Braces for Dramatic Escalation Set to be ‘Bloodier Than Ghouta’

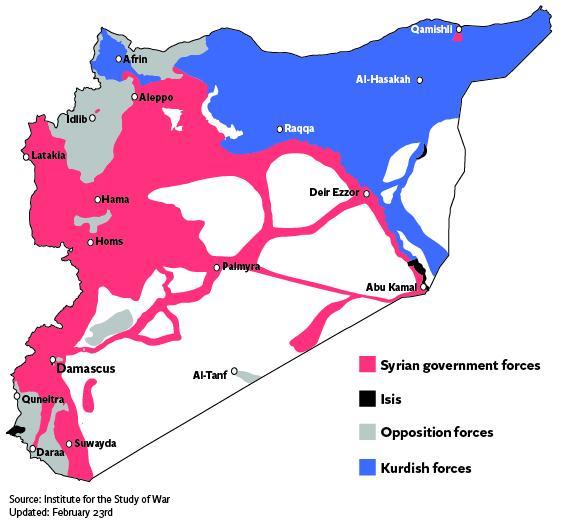

In a field beside an abandoned railway station close to the Turkish border in northern Syria, Kurdish fighters are retraining to withstand Turkish air strikes. “We acted like a regular army when we were fighting Daesh [Isis] with US air support,” says Rojva, a veteran Kurdish commander of the People’s Protection Units (YPG). “But now it is us who may be under Turkish air attack and we will have to behave more like guerrillas.”

Rojva and his brigade have just returned from 45 days fighting Isis in Deir Ezzor province in eastern Syria and are waiting orders which may redeploy them to face the Turkish army that invaded the Kurdish enclave of Afrin on 20 January. Rojva says that “we are mainly armed with light weapons like the Kalashnikov, RPG [rocket propelled grenade launcher] and light machine guns, but we will be resisting tanks and aircraft”. He makes clear that, whatever happened, they would fight to the end.

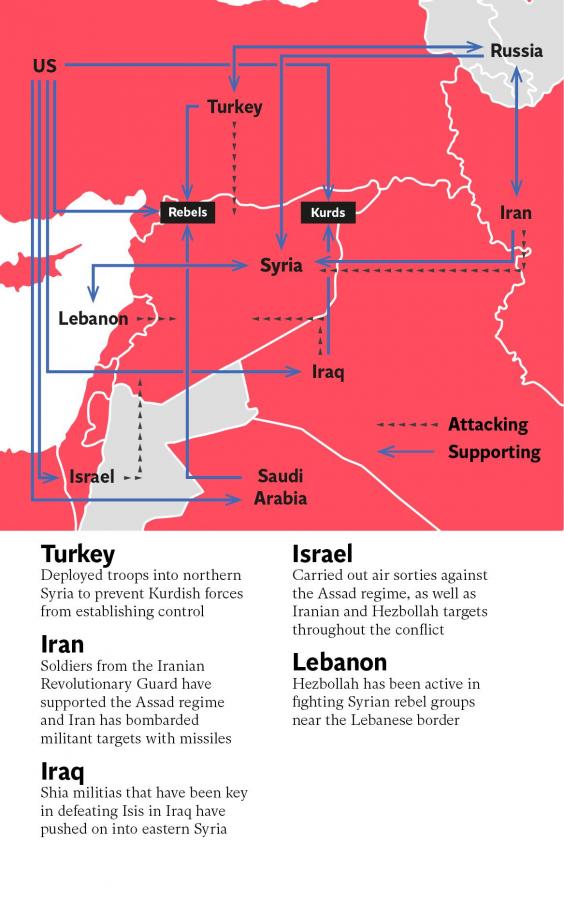

Kurdish and allied Arab units are streaming north from the front to the east of the Euphrates, where Isis is beginning to counter-attack, in order to stop the Turkish advance. Some 1,700 Arab militia left the area for Afrin on Tuesday and Turkey is demanding that the US stop them. The invasion is now in its seventh week and Rojva and his fighters take some comfort in the fact that it is moving so slowly. But the Turkish strategy has been to take rural areas before mowing methodically to surround and besiege Afrin City and residential areas.

The big battles in Afrin are still to come and are likely to be as destructive and bloody as anything seen in Eastern Ghouta, Raqqa or East Aleppo. YPG fighters have battle experience stretching back to at least 2012, much of its gained against fanatical opponents like Isis. The likelihood is that, as in Ghouta, the Turkish generals will seek to avoid the heavy losses inevitable in street fighting and pound Afrin into ruins with air strikes and artillery fire. Civilian casualties are bound to be horrendous.

The Syrian Kurds believe they are facing an existential threat. They believe Turkey wants to eliminate not just the enclave of Afrin, but the 25 per cent of Syria that the Kurds have taken with US backing since 2015. Some think that defeat will mean the ethnic cleansing of Kurds from Afrin, which has traditionally been one of their core majority areas. They cite a speech by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan made the day after the start of the invasion started, claiming that “55 per cent of Afrin is Arab, 35 per cent are the Kurds … and about 7 per cent are Turkmen. [We aim] to give Afrin back to its rightful owners.” There is a suspicion among Kurdish leaders that Erdogan plans to create a Sunni bloc of territory north and west of Aleppo which will be under direct or indirect Turkish control.

The Kurdish leaders are convinced that Erdogan is determined to destroy their de facto state in the long run, but differ about the timing and objectives of the present attack. Elham Ahmad, the co-president of the Syrian Democratic Council that helps administer the Kurdish-held area, believes that the Turkish assault on Afrin, if successful, will set “a precedent for a further Turkish military advance”.

Ahmad had just returned from Afrin where she was born and where her family still lives. “Our convoy of 150 civilian cars was hit by a Turkish air strike,” she said. “We ran away from the cars, but 30 of them were destroyed and one person killed.” She is angry that the outside world is exclusively preoccupied with the bombardment of Eastern Ghouta by President Bashar al-Assad’s forces, but ignores similar bombing and shelling in Afrin where, she says, 204 civilians had been killed, including 61 children, as of last weekend.

She expects that the next Turkish target, if its so-called Operation Olive Branch succeeds in Afrin, will be the Arab city of Manbij that was taken by the YPG in 2016. Strategically placed on the main road from Aleppo to the Kurdish heartlands, with a diversion where part of the highway is held by Turkish forces, it is a prosperous looking place full of shops crammed with goods and produce. Local rumour has it that one small shop recently changed hands for $1m (£720,000). It is the main supply line to the Kurdish zone, the highway crowded with oil tankers bringing crude oil from Kurdish-held oilfields far to the east to the Syrian government refinery at Homs.

If local people are nervous about the prospect of being submerged by the impending battle for northern Syria, they are not showing it. After being occupied by Isis and besieged by the YPG, they have strong nerves. They may also reflect that, if war is coming to their city and its 300,000 people, there is not a lot they can do to avert it. The main reason they might feel secure is a US pledge to defend their city against a Turkish attack, a promise backed up by regular and highly visible patrols of five or six US armoured vehicles carrying large Stars and Stripes. But the US willingness to confront its Nato partner Turkey is nuanced, particularly since Isis was defeated last year, though the movement is not entirely dead.

There is a sense of phoney war on the front line between the forces of the Manbij Military Council and the Turkish army and its allied anti-Assad militias, who are dug in three or four miles north of the city. Most of the front lines in the Syrian civil war are a depressing scene of abandoned and half-wrecked buildings, even when there is no fighting going on. The Manbij front is idyllic by comparison, though just how long it will stay that way is another question.

This is a fertile heavily populated country with a Mediterranean feel to it, its hills and small fields full of olive trees, pines, poplars and almond trees which are covered in little white flowers. There are tractors on the roads and, just behind the front, we drove through the Arab village of Dadat, whose streets full of cheerful-looking children excited by the sight of military vehicles.

A trench and rampart gauged out the hillside by bulldozers zigzags upwards through a green field to a fortified position on a hilltop. Peering through gun slits in a sandbagged post on top of an earth bank, one could see Turkish positions not far away on the far side of the Sajur river. “They have tanks and artillery on every hilltop and they fire randomly with heavy machine guns every night,” says Farhat Kobani, a local commander whose orders come from the Manbij Military Council. The Turkish army is backed up by Ahrar al-Sham, a militant Islamist movement long allied to Turkey, whose men act as auxiliaries.

These exchanges of fire do not seem very serious because everybody, at least in day time, is standing upright in easy range of the other side and Farhat says his men have not suffered any dead or wounded. Phoney war is often derided, but there is a lot to be said for it when compared to the real thing – and, unfortunately, that may not be too far away.