Why the World Is a More Dangerous Place Today Than It Was During the Cold War

On 9 August 2017 President Trump tweeted “My first order as President was to renovate and modernize our nuclear arsenal. It is now far stronger and more powerful than ever before.”

This statement of US achievement and nuclear policy was apparently intended to intimidate the leader of North Korea, Kim Jong Un, who tested a nuclear-capable ballistic missile three months later, following which the US president issued an insulting tweet that referred to him as “Little Rocket Man.” The level of international dialogue and diplomacy sank to yet a new low which was enthusiastically reciprocated by Kim, but Trump gave a rare exhibition of common sense on 11 November 2017 by asking “When will all the haters and fools out there realize that having a good relationship with Russia is a good thing, not a bad thing. There [meaning they’re] always playing politics — bad for our country . . .”

How very true, and how much better for the world had such a positive attitude been allowed to flourish along with dialogue. But then everything went screaming downhill. Along came Washington’s aggressive Nuclear Posture Review which emphasised enlargement of nuclear weapons’ capabilities and followed from the US National Defence Strategy which strongly advocates massive military expansion, naming Russia specifically no less than 127 times, compared with 62 references to North Korea, 47 to China and 39 to Iran.

The antagonistic muscle of the US military-industrial complex has been nourished by the circus of the “Russiagate” investigations in Washington which attempted to prove that Moscow had organised the 2016 election results by persuading countless millions of people on social media sites that red was blue and Democratic donkeys were really Republican elephants. Or the other way round. It was all rubbish, but the US-European anti-Russia campaign was then given enormous impetus by the collapse in England from apparent poisoning of a retired, BMW-driving British spy, a former Russian citizen.

The poisoning was effected by a chemical agent, and blame for the event was immediately laid at Russia’s door. The British foreign minister Boris Johnson is a sad joke, but he’s politically powerful and a threat to the prime minister, Theresa May, so he continues in his post and makes statements such as “Russia is the only country known to have developed this type of agent. I’m afraid the evidence is overwhelming that it is Russia.” The fact that there is no evidence whatever that Russia was involved is ignored, because the western world has been convinced that Russia is guilty of this poisoning — and of countless other things.

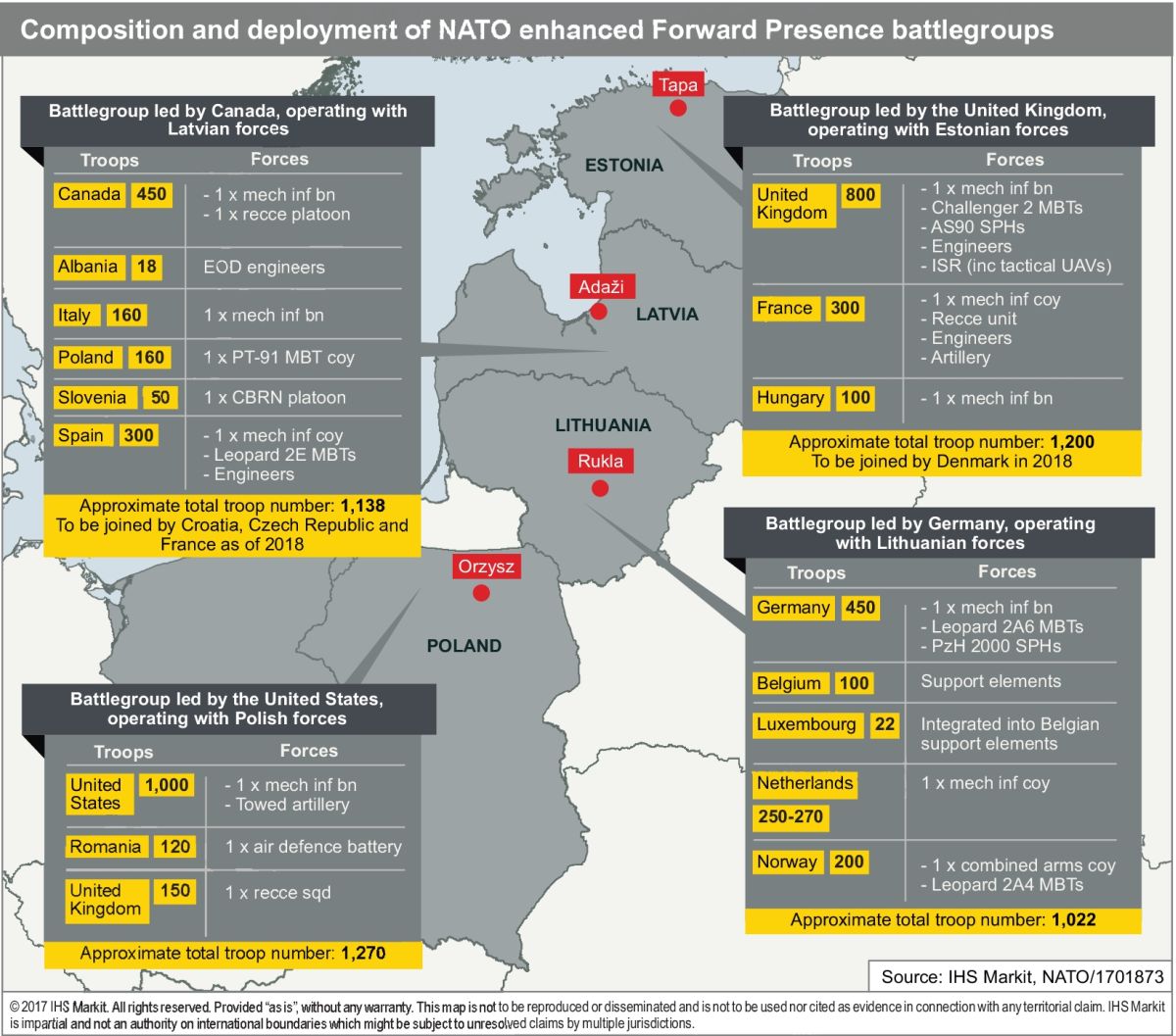

The heightened anti-Russia feeling is most welcome to the US-NATO military alliance, which has been energetic in developing its ‘Enhanced Forward Presence’ along Russia’s borders. Its belligerent posture has been hardening since NATO began to expand in 1997, which was entirely contrary to what had been agreed seven years previously. As recorded by the Los Angeles Times, “In early February 1990, US leaders made the Soviets an offer. According to transcripts of meetings in Moscow on February 9, then-Secretary of State James Baker suggested that in exchange for cooperation on Germany, US could make “iron-clad guarantees” that NATO would not expand “one inch eastward.” Less than a week later, Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev agreed to begin reunification talks. No formal deal was struck, but from all the evidence, the quid pro quo was clear: Gorbachev acceded to Germany’s western alignment and the US would limit NATO’s expansion. Nevertheless, great powers rarely tie their own hands. In internal memorandums and notes, US policymakers soon realized that ruling out NATO’s expansion might not be in the best interests of the United States. By late February, Bush and his advisers had decided to leave the door open.”

The doors towards Russia’s borders were not only open: they had on the other side a welcoming galaxy of nations anxious to enjoy all the financial benefits that would descend upon them from the deep and generous pockets of the Washington-Brussels military machine. The US and other NATO members pitched forward with missile-armed ships in the Baltic and the Black Sea, with electronic surveillance and command aircraft flying as close as they could to Russian airspace, along with deployment of nuclear-capable combat aircraft and more ground troops in expansion of the Enhanced Forward Presence.

The recent surge in anti-Russia news and comment in almost all US and UK media is a boon and a blessing for the rickety and incompetent NATO alliance, but in responsible circles there is concern about its nuclear posture — and especially that of the United States.

The nuclear threat from Washington is growing, and in spite of the fact that analysts such as Bruno Tertrais of the Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique note that Russia’s stance has been misinterpreted, the tide of anti-Russian western opinion cannot now be stopped or even reduced. The requirement for provision of evidence is disregarded and in no sphere is this more marked than in western pronouncements about Russian nuclear policy.

As Dr Tertrais points out, “The dominant narrative about Russia’s nuclear weapons in Western strategic literature since the beginning of the century has been something like this: Russia’s doctrine of ‘escalate-to-de-escalate’ and its large-scale military exercises show that Moscow is getting ready to use low-yield, theatre nuclear weapons to stop NATO from defeating Russia’s forces, or to coerce the Atlantic Alliance and end a conflict on terms favourable to Russia. All the elements of this narrative, however, rely on weak evidence — and there is strong evidence to counter most of them.”

One of the most disturbing things is the attitude to the Nuclear Posture Review of many nuclear experts in the West. But some of these nuclear war enthusiasts might strike people as bizarre in their approach. As reported by Defence News “Rebeccah Heinrichs, a nuclear analyst with the Hudson Institute, thinks the Pentagon is on the right path, noting that “if the Russians have a weapon delivery option, they’re putting a nuke on it” at the moment. “Clearly the Russians believe that they could possibly pop off a low yield nuke and we would not have an appropriate response, and our only option would essentially be to end the war rather than go all-in with strategic nuclear weapons. . . “

It may be because I have had some association with nuclear delivery systems and their hideous effects that I take offence at clever little analysts referring to despatch and detonation of nuclear weapons as “popping off.” The weapon that would be “popped off” — whatever it might be — would kill hundreds, perhaps thousands of people, and would contaminate vast areas of land. A “low yield nuke” as it is so lightly dismissed, is not an inconsequential weapon.

A long time ago in Germany I commanded a troop of rocket launchers that were tasked to fire “low yield” Honest John missiles in the event of war in Europe. We knew that these things would cause immense damage because the W7 warhead had a variable yield of up to 20 kilotonnes — just about that of the Nagasaki bomb that killed about 75,000 human beings. Sure, our warheads might only have been a fraction of that (we’ll never know), but even then I object to intellectuals saying they might have been “popped off” like modern-day “low-yield nukes,” because we would have died within a few minutes of firing these things, not long after we had killed our thousands of victims, most likely from retaliation but also because the maximum range of our rockets was about 25 kilometres and the fall-out effects would have been pretty swift.

Then you read the pronouncements of such important people as Air Force General John Hyten, the senior US nuclear deliveryman, commanding US Strategic Command, who said on February 28 that “Russia is the most significant threat just because they pose the only existential threat to the country right now. So we have to look at that from that perspective.”

He should get together with Rebeccah Heinrichs. They could discuss where and how to pop off a weapon that would lead to world destruction. The nuclear threat looms large.