Poland and Sweden Are Building a “Baltic Ring”

The global trend of connectivity is moving to Northern and Central-Eastern Europe as these regions’ two former Great Powers join forces to deepen their integration with one another and build a new power bloc in the continent.

Poland and Sweden are two of Europe’s oldest Great Powers, though both of them are centuries past their prime and have since seen their influence eclipsed by former competitors such as Russia, Germany, and the UK. The post-Brexit geopolitical reality and Trump’s embrace of his successor’s “Lead From Behind” policy of regional blocs have unexpectedly opened up unprecedented strategic opportunities for these two “has-beens”, and they’re now tacitly cooperating with one another in building a new power bloc in Europe. Sweden – the leader of the “Viking Bloc” of Scandinavian countries and Finland –, is joining forces with Poland – the aspiring hegemon of a “Neo-Commonwealth” that Warsaw wishes will one day rule over the “Three Seas Initiative” – in coordinating the construction of several integrational corridors that will altogether lead to the emergence of a “Baltic Ring”.

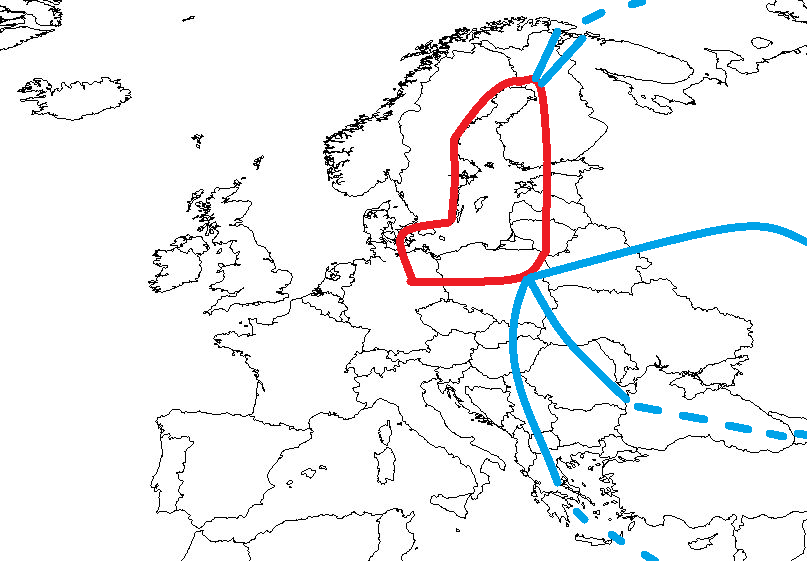

A high-speed rail route by the name of “Rail Baltica” is currently being built between Poland and Estonia, whenceforth it might be expanded under the Baltic to Finland through the so-called “Talsinki Tunnel”. Once in the northern nation, existing rail routes could be connected to Sweden via the prospective “Bothnian Corridor”, after which people and freight could link up with Germany through the Swedish-Danish-German rail network that’s already in use. In addition, the German component is already connected with Poland, thereby completing the Baltic Ring. A related element of this developing integrational network is Poland’s planned “Baltic Pipe” that will go through Denmark and bring Norwegian offshore gas to the country. The below map provides a rudimentary glimpse of how this might look if it’s ever completed and fully enters into operation:

It also shouldn’t be forgotten that there are already several ferry services between Sweden and the eastern-southern shore of the Baltic Sea, meaning that the Scandinavian country already has maritime access to the Baltic States and Poland. Because of its sheer demographic and economic size, Germany is clearly a crucial part of the Baltic Ring, but it’s not indispensable in the sense that Swedish-Polish connectivity ventures can still continue without it. Furthermore, these said initiatives are leading to the creation of spheres of influence in Northern and Central-Eastern Europe, whereby Stockholm is once again exerting leadership in its previous imperial realm in the northern part of the Baltic Sea while Warsaw is doing the same along its southern-eastern shoreline.

It also shouldn’t be forgotten that there are already several ferry services between Sweden and the eastern-southern shore of the Baltic Sea, meaning that the Scandinavian country already has maritime access to the Baltic States and Poland. Because of its sheer demographic and economic size, Germany is clearly a crucial part of the Baltic Ring, but it’s not indispensable in the sense that Swedish-Polish connectivity ventures can still continue without it. Furthermore, these said initiatives are leading to the creation of spheres of influence in Northern and Central-Eastern Europe, whereby Stockholm is once again exerting leadership in its previous imperial realm in the northern part of the Baltic Sea while Warsaw is doing the same along its southern-eastern shoreline.

Finland and Estonia, which are culturally similar nations, can be grouped together as a single strategic entity for the intent of this analysis, and thus might represent a “buffer zone” of sorts, though in a “friendly” way because Poland and Sweden aren’t expected to compete in any traditional manner. In fact, while the “19th-Century Great Power Chessboard” paradigm is veritably in effect today, it doesn’t necessarily take on the same contours as its historical namesake because large-scale conventional warfare between neighboring powers over the “proxy states” between them isn’t anticipated to be a defining element in all cases. Rather, in the instance of Poland and Sweden, these two historically rivaling empires won’t clash, but cooperate, in their shared Baltic Ring space per the logic of contemporary European geopolitics and the win-win zeitgeist of New Silk Road integration.

No one should be under any assumptions that the Baltic Ring would be a Russian-friendly entity, however, since Poland’s political Russophobia is now infecting Sweden, and both Great Power cores are competing with one another in virtue signaling to their unipolar American patron which of the two hates Moscow the most nowadays. This is clearly disadvantageous to Russian interests because of the implication that it has for drawing NATO closer to its borders under manufactured pretexts, but it works out to Poland and Sweden’s benefit because they’re able to secure Washington’s support in their collective quest to carve out spheres of influence in Europe that stand apart from the generally German-controlled EU as a whole. This “decentralization” trend also interestingly aligns with the global tendency of power shifting ever eastward in the 21st century, which is more topical in this sense that it might initially appear.

The Baltic Ring isn’t just a regional collection of states and trading networks inside of Europe, but could one day function as its own Silk Road node in a Multipolar World Order given its connectivity prospects with China. The logical access route to the People’s Republic would be across Russia via the Eurasian Land Bridge, but that might not be politically feasible given the geopolitics of the New Cold War and Poland-Sweden’s hysterical Russophobia. Nevertheless, maritime routes exist along the northern and southern axes, namely through Finland’s desire to link up with the “Artic/Ice Silk Road” via either the Russian port of Murmansk (which is less probable if US-provoked Russian-European tensions persist) or the nearby Norwegian one of Kirkenes, and the possibility of expanding the Balkan Silk Road from the Greek port of Piraeus all the way northward to Poland’s Baltic Ring junction.

In addition, the more logistically complex but currently active corridor through the Caucasus also represents another geographic workaround through which China can connect with the Baltic Ring without going through Russia (keeping in mind that that Poland-Sweden will probably try to avoid having Russia cash in on this trade route however much as they possibly can). The Azerbaijani-Georgian segment of the newly unveiled BTK Railway theoretically allows for the Baltic Ring countries to trade with China via the Black Sea, Caucasus, Caspian Sea, and Central Asia (maritime, mainland, maritime, mainland). If Armenia ever fully develops its Black Sea-Persian Gulf Corridor plans, then a CPEC+ connection to China could also be established across the Black Sea, Caucasus, Iran, and Pakistan, though it’ll still be some years before this is even possible.

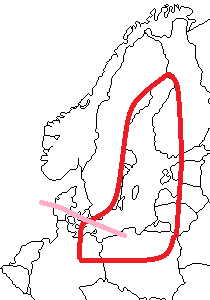

From a larger Silk Road perspective, here’s how the Baltic Ring’s connectivity potentials with China look on the map:

The four most important geographic nodes are Finland, Sweden, Poland, and Romania, with the countries of the former Yugoslavia too weak and disorganized to function as the single political-economic unit that they need to be in order to maximally benefit from this and therefore representing nothing more than a transit space in this construction. Out of the four-mentioned states, however, Poland is by far the most important since its population (which strategically translates into labor potential and market size) is almost as much as the total of Sweden, Finland, and Romania’s combined. Excluding Russia from the equation, then China’s Silk Road access routes to Poland go through Sweden-Finland in the north and Romania-former Yugoslavia in the south, all of which have the potential to profit from enhanced Chinese-Polish connectivity via the Baltic Ring and “Three Seas” concepts if they wisely leverage their strategic economic positions.

All in all, the evident pattern on display is that the center of Europe’s strategic gravity is slowly but surely shifting eastward away from Germany and towards Poland & Sweden, with these two “has-been” Great Powers coming together through a new cooperative framework in order to build the Baltic Ring connectivity corridor that they plan to link up with China via the New Silk Roads. The political Russophobia of this developing power center is troubling but not surprising, though the long-term consequences of it might be that China’s envisioned Silk Road connectivity with Europe via the Eurasian Land Bridge could be obstructed as a result. Even so, the Arctic/Ice Silk Road, the Caucasus Corridor (whether across the Caspian or through Iran), and the Balkan Silk Road present northern and southern workarounds for maintaining the Baltic Ring’s commercial access to China.

What this comprehensively signifies is that Poland is becoming the centerpiece of post-European geopolitics in the entire part of the bloc east of Germany, seeing as how it’s one of the most crucial nodes in China’s One Belt One Road global vision of New Silk Road connectivity, and that the strategic implications of this emerging reality could be far-reaching when it comes to the balance of power in the New Cold War. The Polish-led “Three Seas Initiative” and Warsaw’s joint leadership of the Baltic Ring with Stockholm aren’t welcome developments from Russia’s perspective because they’re clearly US-backed moves to deepen American proxy influence all along its rival’s western borderland region, but on the other hand, this inadvertently creates certain irresistible opportunities for China to expand its influence to the furthest reaches of the Eurasian supercontinent and work on silently spreading multipolarity there.