For the Chinese Quadrilateral Peace Treaty Draft on the Results of the Korean War

The beginning of April saw a curious disinformation flood initiated by the Japanese media and then supported by the South Korean media. Allegedly, on March 9, 2018, while speaking on the phone with the US President Donald Trump, the Chinese General Secretary Xi Jinping suggested a new format of the Korean settlement, which excludes the participation of Russia and Japan. Trump allegedly emphasized that the Chinese participation in denuclearizing North Korea is critical and claimed that China had made a commitment to support the North Korea disarmament verification.

Quoting the diplomatic sources that are “close to Washington-Beijing relations”, the Kyodo agency informs that, in order to maintain peace on the Korean peninsula, Xi Jinping called for creating a quadrilateral structure including China, North Korea, South Korea and the USA, and that this suggestion envisaged signing a peace treaty, which would replace the truce that ended the Korean War of 1950-1953.

The South Korean newspaper Dong-Allbo also emphasizes the main point of the Beijing initiative – the suggestion to sign a peace treaty. According to its data, Xi Jinping shared this idea with Kim Jong-un during their sensational meeting in Beijing on March 26.

At the moment, while this article is being written, both Beijing and Pyongyang keep silent about it, but whether it’s just a rumor or not, the alleged information is rather interesting.

If it is a rumor – then it reflects perfectly the apprehension of Japan that the Korean settlement will exclude its participation. However, to tell the truth, it has not only to do with the anti-Japan ideology of both Koreas, but also with the fact that the official Tokyo has done a lot to get excluded that way. During the hexalateral talks, Japan was de-facto “the second voice” of the US and sometimes rejected constructive drafts even faster than the US itself. For instance, after signing the joint statement of 2005, Tokyo openly claimed that it would not fulfill its part of the arrangement, since Tokyo and Pyongyang still had the abduction problem unresolved. Nota bene: they got away with it.

As for the quadrilateral format on the whole, one might remember that in the beginning of the hexalateral talks, the original parties were only to include both Koreas, China and the US. Naturally, China was acting as the host and tried to establish itself as the power that suggested an idea and would assist in resolving the crisis as the guiding force. Unwilling to become the minority, the US suggested to include Japan on the pretext that it is located nearby and that it may become another subject of the North Korean threat. It is purported that in response to this, Kim Jong-il suggested that Russia be included as well, “since it is also located nearby”, and this way the hexalateral talks acquired the format of “2 Koreas + 4 neighboring countries”.

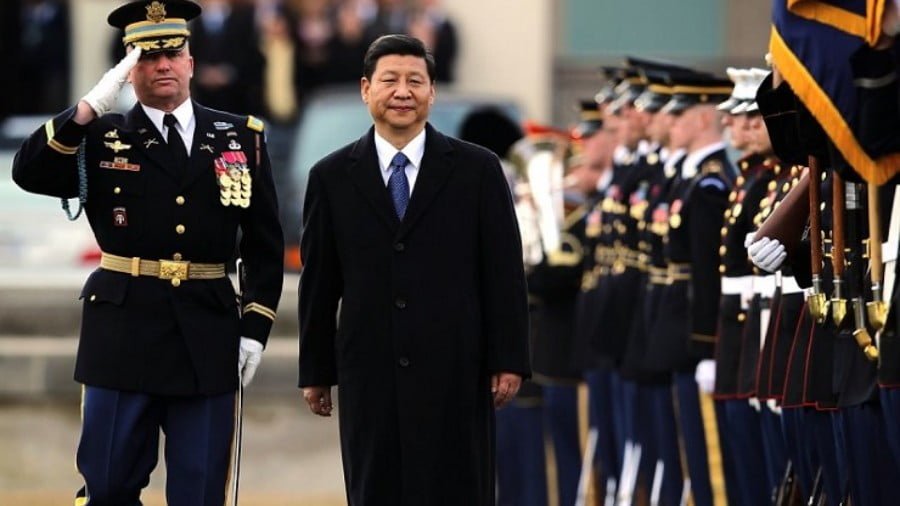

It is clear that reviving the hexalateral format is improbable, at least because using it to discuss the North Korean denuclearization seems strange. However, such a multilateral format is very convenient for China, which will see to it that the settlement of both the North Korean nuclear missile program and the inter-Korean crisis will not leave China out. For General Secretary Xi Jinping, considering the amendments to the Party Charter and the Chinese Constitution, which could give him the life-long rule, this is critical, because in this situation he receives the status if not of a suzerain, then at least that of a wise arbitrator. And vice versa, if China is left out of the inter-Korean settlement due to the too intense inter-Korean rapprochement or Pyongyang’s possible attempts to balance between China and the US (just as the North Korean leadership did so well between Beijing and Moscow back in the day), this will damage its prestige.

Barack Obama also suggested that the Korean issue be resolved with the help of China, however his concept of G2, or Chimerica, failed exactly on the Korean issue: if all the problems are to be solved together, then China should not always give the go-ahead to the US, and if the globe is to be divided into the spheres of influence, then North Korea (as well as South Korea) is sure to find itself in the Chinese one.

Therefore, any talk of this kind is to be considered within the context of the general trend, targeted at China’s attempts to strengthen its control of the situation after Kim Jong-un’s visit to Beijing. It would be wrong to say that the Olympic rapprochement was met with surprise, but the author of this article has heard from several experts that “pushing too much with the sanctions as per the US request, the Chinese got one over on themselves”. The relations between the two countries cooled off and Pyongyang tried to re-orient itself to other “big countries”.

The Chinese initiative to sign a quadrilateral peace treaty is much more interesting. The thing is, the Korean War is de-facto still going on. And this has to do with the circumstances of the 1953 Ceasefire Agreement and what became of it. Of course, neither the US, nor China participated in this war under their national flags. The US used the UN flag, despite having the vast majority in all the branches of the armed forces, and China took part in the form of “volunteers”. However, the public understands it purely as a diplomatic ploy, aimed at giving the war a certain framework and scale. And, at some point, the UN Unified Command turned very well into the “joint command” (of the US and South Korea).

The truce agreement was signed by North Korea, China and the US. South Korea, dominated by the odious regime of Syngman Rhee, was going to wage war as long as possible, but the 1953 Mutual Defense Treaty deprived it of the opportunity – according to the document, even in times of peace, the South Korean army was subordinate not to the South Korean President, but to the US command. This was made to prevent the Blue House starting a war without it first being sanctioned by the White House.

However, as we already mentioned, in 1958, the US technically terminated the agreement by basing their tactical nuclear weapons within the territory of South Korea and unilaterally informing the other party about it. Since the agreement clearly forbade any deployment of new weapons on the peninsula, it can be legally considered inoperative. However, North Korea continued to follow the agreement, though occasionally, especially in view of the Korean Peninsula Nuclear Issue, threatened to abandon it – and in 2016 it did so.

In this context, a peace treaty by all the states involved in that conflict, would be a reasonable step in comparison with an exclusively inter-Korean or US-North Korean agreement. After all, one has to remember that the Chinese volunteers remained in the country until 1958 and the 1961 Pyongyang-Beijing treaty, even after being somewhat “rebalanced”, still has a paragraph that should North Korea be invaded by another state, China would come to its rescue again.

Only time will show, to what extent the new peace treaty will just capture the current situation or include a détente commitment, mutual guarantees or a waiver from using military force. Theoretically, drafting a document with no ambiguous interpretations is quite feasible, but there are limits to optimism, because, first, one can sign a treaty without ratifying it, as it happened with the Framework Agreement. Secondly, the North-South peace treaty can be considered to be the mutual recognition of each other as subjects to policy, which Seoul is surely reluctant to do and Pyongyang probably won’t do either. Let us remind you that the South Korean Constitution is in force on the whole Korean peninsula, as per the National Security Act, North Korea is not a state at all, but rather an anti-state organization. As a result, South Korea and North Korea use different ethnonyms to denote the Korean state, even though this can be translated neither into English, nor into Russian. That is why, relatively speaking, in the South, the North is called “The North Republic of Korea”, and in the North, the South is called “the South Democratic People’s Republic of Korea”. Consequently, the inter-Korean trade was considered neither foreign, nor domestic, and the inter-Korean issues are dealt with not by the Foreign Office, but the specifically designed Ministry of Unification, and when ex-president Lee Myung-bak considered disbanding it, it caused such an uproar that it proved easier to let it be.

And even though the cool head of the author advises skepticism, his heart hopes that the Korean War will finally come to its legal end.