Are You Ready for the New Wave of Genetically Engineered Foods?

Everyone loves a feel-good story about the future. You’ve probably heard this one: high-tech foods enhanced by science will feed the 9 billion people expected on the planet by 2050. Food made in labs and crops and animals genetically engineered to grow faster and better will make it possible to feed the crowded world, according to stories that spin through our institutions of media and education.

“6th grade students brainstorming big biotech ideas to #Feedthe9″ touted a recent tweet tagged to the chemical industry’s promotional website GMOAnswers. Student ideas included “breed carrots to have more vitamins” and “corn that will grow in harsh winter conditions.”

“6th grade students brainstorming big biotech ideas to #Feedthe9″ touted a recent tweet tagged to the chemical industry’s promotional website GMOAnswers. Student ideas included “breed carrots to have more vitamins” and “corn that will grow in harsh winter conditions.”

It all sounds so promising until you look at the realities behind the rhetoric.

For starters, in a country that leads the world in growing genetically modified organisms (GMOs), millions go hungry. Reducing food waste, addressing inequality and shifting to agroecological farming methods, not GMOs, are the keys to world food security, according to experts at the United Nations. Most genetically engineered foods on the market today have no consumer benefits whatsoever; they are engineered to survive pesticides, and have greatly accelerated the use of pesticides such as glyphosate, dicamba and soon 2,4D, creating what environmental groups call a dangerous pesticide treadmill.

Despite decades of hype about higher nutrients or heartier GMO crops, those benefits have failed to materialize. Vitamin-A enhanced Golden Rice, for example – “the rice that could save a million kids a year,” reported Time magazine 17 years ago – is not on the market despite millions spent on development. “If golden rice is such a panacea, why does it flourish only in headlines, far from the farm fields where it’s intended to grow?” asked Tom Philpott in Mother Jones article titled, WTF Happened to Golden Rice?

“The short answer is that the plant breeders have yet to concoct varieties of it that work as well in the field as existing rice strains…When you tweak one thing in a genome, such as giving rice the ability to generate beta-carotene, you risk changing other things, like its speed of growth.”

Nature is complex, in other words, and genetic engineering can produce unexpected results.

Consider the case of the Impossible Burger.

The plant-based burger that “bleeds” is made possible by genetically engineering yeast to resemble leghemoglobin, a substance found in soybean plant roots. The GMO soy leghemoglobin (SLH) breaks down into a protein called “heme,” which gives the burger meat-like qualities — its blood-red color and sizzle on the grill — without the environmental and ethical impacts of meat production. But the GMO SLH also breaks down into 46 other proteins that have never been in the human diet and could pose safety risks.

The plant-based burger that “bleeds” is made possible by genetically engineering yeast to resemble leghemoglobin, a substance found in soybean plant roots. The GMO soy leghemoglobin (SLH) breaks down into a protein called “heme,” which gives the burger meat-like qualities — its blood-red color and sizzle on the grill — without the environmental and ethical impacts of meat production. But the GMO SLH also breaks down into 46 other proteins that have never been in the human diet and could pose safety risks.

As The New York Times reported, the burger’s secret sauce “highlights the challenges of food tech.” The story was based on documents obtained by ETC Group and Friends of the Earth under a Freedom of Information Act request – documents the company probably hoped would never see the light of day. When Impossible Foods asked the Food and Drug Administration to confirm its GMO ingredient was “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS), the Times reported, the agency instead “expressed concern that it has never been consumed by humans and may be an allergen.”

FDA officials wrote in notes describing a 2015 call with the company, “FDA stated that the current arguments at hand, individually and collectively, were not enough to establish the safety of SLH for consumption.” But, as the Times story explained, the FDA did not say the GMO leghemoglobin was unsafe, and the company did not need the approval of FDA to sell its burger anyway.

The arguments presented did not establish safety – FDA

So Impossible Burger is on the market with the company’s assurances of safety and most consumers are in the dark about what’s in it. While the GMO process is explained on the website it is not marketed that way at the point of sale. On a recent visit to a Bay Area restaurant that sells the Impossible Burger, a customer asked if the burger was genetically modified. He was inaccurately told, “no.”

Lack of government oversight, unknown health risks and consumers left in the dark – these are recurring themes in the unfolding narrative about the Wild West of genetic engineering experimentation that is galloping toward a store near you.

A GMO By Any Other Name …

Synthetic biology, CRISPR, gene editing, gene silencing: these terms describe the new forms of genetically engineered crops, animals and ingredients that companies are rushing to get onto the market.

Synthetic biology, CRISPR, gene editing, gene silencing: these terms describe the new forms of genetically engineered crops, animals and ingredients that companies are rushing to get onto the market.

The old method of genetic engineering, called transgenics, involves transferring genes from one species to another. With the new genetic engineering methods – what some environmental groups call GMOs 2.0 – companies are tampering with nature in new and possibly riskier ways. They can delete genes, turn genes on or off, or create whole new DNA sequences on a computer. All these new techniques are GMOs in the way consumers and the U.S. Patent Office consider them – DNA is altered in labs in ways that can’t occur in nature, and used to make products that can be patented. There are a few basic types of GMOs 2.0.

Synthetic biology GMOs involve changing or creating DNA to artificially synthesize compounds rather than extract them from natural sources. Examples include genetically engineering yeast or algae to create flavors such as vanillin, stevia and citrus; or fragrances like patchouli, rose oil and clearwood – all of which may already be in products.

Synthetic biology GMOs involve changing or creating DNA to artificially synthesize compounds rather than extract them from natural sources. Examples include genetically engineering yeast or algae to create flavors such as vanillin, stevia and citrus; or fragrances like patchouli, rose oil and clearwood – all of which may already be in products.

Some companies are touting lab-grown ingredients as a solution for sustainability. But the devil is in the details that companies are reticent to disclose. What are the feedstocks? Some synthetic biology products depend on sugar from chemical-intensive monocultures or other polluting feedstocks such as fracked gas. There are also concerns that engineered algae could escape into the environment and become living pollution.

And what is the impact on farmers who depend on sustainably grown crops? Farmers around the world are worried that lab-grown substitutes, falsely marketed as “natural,” could put them out of business. For generations, farmers in Mexico, Madagascar, Africa and Paraguay have cultivated natural and organic vanilla, shea butter or stevia. In Haiti, the farming of vetiver grass for use in high-end perfumes supports up to 60,000 small growers, helping to bolster an economy ravaged by earthquake and storms.

Does it make sense to move these economic engines to South San Francisco and feed factory-farmed sugar to yeast in order to make cheaper fragrances and flavors? Who will benefit, and who will lose out, in the high-tech crop revolution?

Genetically engineered fish and animals: dehorned cattle, naturally castrated pigs, and chicken eggs engineered to contain a pharmaceutical agent are all in the genetic experimentation pipeline. An all-male “terminator cattle” project – with the code name “Boys Only” – aims to create a bull that will father only male offspring, thereby “skewing the odds toward maleness and making the (meat) industry more efficient,” reported MIT Technology Review.

Genetically engineered fish and animals: dehorned cattle, naturally castrated pigs, and chicken eggs engineered to contain a pharmaceutical agent are all in the genetic experimentation pipeline. An all-male “terminator cattle” project – with the code name “Boys Only” – aims to create a bull that will father only male offspring, thereby “skewing the odds toward maleness and making the (meat) industry more efficient,” reported MIT Technology Review.

What could go wrong?

The geneticist working on the terminator cattle, Alison Van Eenennaam of the University of California, Davis, is lobbying FDA to reconsider its 2017 decision to treat CRISPR-edited animals as if they were new drugs, thereby requiring safety studies; she told the MIT Review that would “put a huge regulatory block on using this gene-editing technique on animals.” But shouldn’t there be requirements for studying the health, safety and environmental impacts of genetically engineered foods, and a framework for considering the moral, ethical and social justice implications? Companies are pushing hard for no requirements; in January, President Trump talked about biotechnology for the first time during his presidency and made a vague declaration about “streamlining regulations.”

The only GMO animal on the market so far is the AquaAdvantage salmon engineered with the genes of an eel to grow faster. The fish is already being sold in Canada, but the company won’t say where, and US sales are held up due to “labeling complications.” The urge for secrecy makes sense from a sales perspective: 75% of respondents in a 2013 New York Times poll said they would not eat GMO fish, and about two-thirds said they would not eat meat that had been genetically modified.

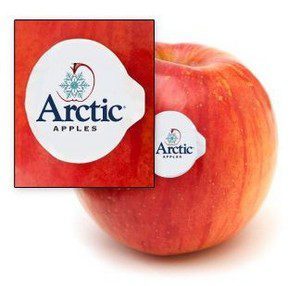

Gene silencing techniques such as RNA interference (RNAi) can turn genes off to create particular traits. The non-browning Arctic Apple was engineered with RNAi to turn down the expression of genes that cause apples to become brown and mushy. As the company explains on its website, “when the apple is bitten, sliced, or otherwise bruised … no yucky brown apple left behind.”

Gene silencing techniques such as RNA interference (RNAi) can turn genes off to create particular traits. The non-browning Arctic Apple was engineered with RNAi to turn down the expression of genes that cause apples to become brown and mushy. As the company explains on its website, “when the apple is bitten, sliced, or otherwise bruised … no yucky brown apple left behind.”

Are consumers actually asking for this trait? Ready or not here it comes. The first GMO Arctic Apple, a Golden Delicious, began heading for test markets in the Midwest last month. Nobody is saying exactly where the apples are landing, but they won’t be labeled GMO. Look out for the “Arctic Apples” brand if you want to know if you’re eating a genetically engineered apple.

Gene editing techniques such as CRISPR, TALEN or zinc finger nucleases are used to cut DNA in order to make genetic changes or insert genetic material. These methods are faster and touted as more precise than the old transgenic methods. But the lack of government oversight raises concerns. “There can still be off-target and unintended effects,” explains Michael Hansen, PhD, senior scientist of Consumers Union. “When you alter the genetics of living things they don’t always behave as you expect. This is why it’s crucial to thoroughly study health and environmental impacts, but these studies aren’t required.”

Gene editing techniques such as CRISPR, TALEN or zinc finger nucleases are used to cut DNA in order to make genetic changes or insert genetic material. These methods are faster and touted as more precise than the old transgenic methods. But the lack of government oversight raises concerns. “There can still be off-target and unintended effects,” explains Michael Hansen, PhD, senior scientist of Consumers Union. “When you alter the genetics of living things they don’t always behave as you expect. This is why it’s crucial to thoroughly study health and environmental impacts, but these studies aren’t required.”

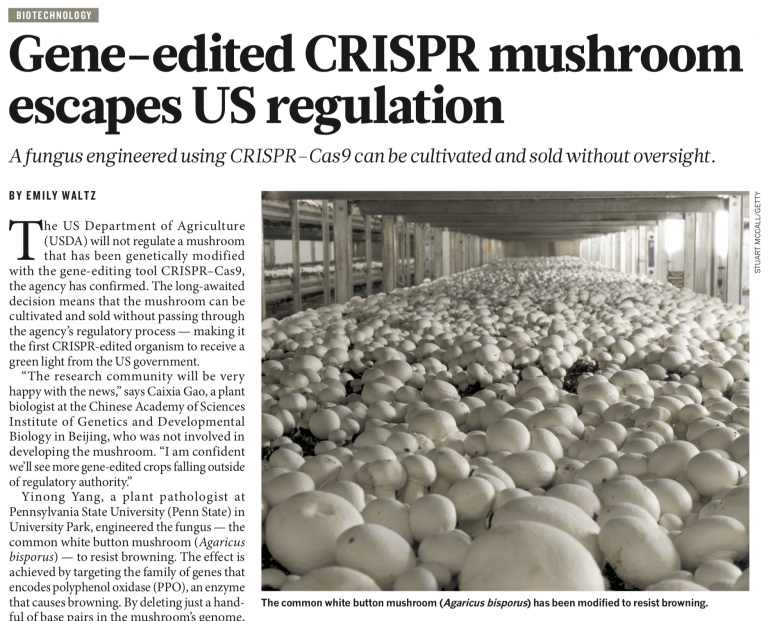

A non-browning CRISPR mushroom escaped US regulation, as Nature reported in 2016. A new CRISPR canola oil, engineered to tolerate herbicides, is in stores now and may even be called “non-GMO,” according to Bloomberg, since the US Department of Agriculture has “taken a pass” on regulating CRISPR crops. The story noted that Monsanto, DuPont and Dow Chemical have “stepped through the regulatory void” and struck licensing deals to use the gene-editing technology.

And that raises another red flag with the narrative that new GMOs will provide consumer benefits that the old transgenic methods didn’t. “Just because the techniques are different doesn’t mean the traits will be,” Dr. Hansen pointed out. “The old method of genetic engineering was used mostly to make plants resist herbicides and increase sales of herbicides. The new gene editing techniques will probably be used in much the same way, but there are some new twists.”

Corporate Greed Versus Consumer Needs

The world’s largest agrichemical companies own the majority of seeds and pesticides, and they are consolidating power in the hands of just three multinational corporations. Bayer and Monsanto are closing in on a merger, and the mergers of ChemChina/Syngenta and DowDuPont are complete. DowDuPont just announced its agribusiness unit will operate under the new name Corteva Agriscience, a combination of words meaning “heart” and “nature.”

The world’s largest agrichemical companies own the majority of seeds and pesticides, and they are consolidating power in the hands of just three multinational corporations. Bayer and Monsanto are closing in on a merger, and the mergers of ChemChina/Syngenta and DowDuPont are complete. DowDuPont just announced its agribusiness unit will operate under the new name Corteva Agriscience, a combination of words meaning “heart” and “nature.”

No matter what re-branding tricks they try, these corporations have a nature we already know: all of them have long histories of ignoring the warnings of science, covering up the health risks of dangerous products and leaving behind toxic messes – Bhopal, dioxin, PCBs, napalm, Agent Orange, teflon, chlorpyrifos, atrazine, dicamba, to name just a few scandals.

The future-focus narrative obscures that sordid past and the present reality of how these companies are actually using genetic engineering technologies today, mostly as a tool for crops to survive chemical sprays. To understand how this scheme is playing out on the ground in leading GMO-growing pesticide-using areas, read the reports about birth defects in Hawaii, cancer clusters in Argentina, contaminated waterways in Iowa and damaged cropland across the Midwest.

The future of food under the control of big agribusiness and chemical corporations is not hard to guess – more of what they are already trying to sell us: GMO crops that drive up chemical sales and food animals engineered to grow faster and fit better in factory farm conditions, with pharmaceuticals to help. It’s a great vision for the future of corporate profits and concentration of wealth and power, but not so great for farmers, public health, the environment or consumers who are demanding a different food future.

Growing numbers of consumers want real, natural food and products. They want to know what’s in their food, how it was produced and where it came from. For those who want to be in the know about what they are eating, there is still a surefire way to avoid old and new GMOs: buy organic. The Non-GMO Project verified certification also ensures products are not genetically engineered or made with synthetic biology.

It will be important for the natural foods industry to hold the line on the integrity of these certifications against the wild stampede of new GMOs.