Take Your Pick: Chinese or American Missiles in the South China Sea?

China’s reported deployment of anti-ship and cruise missiles to its reclaimed islands in the South China Sea was the inevitable action of a country that chose to act first in order to thwart its American adversary from doing the same thing at a more disadvantageous time in the future.

All of Asia seems to be talking about what’s being framed in the Mainstream Media as China’s “provocative” decision to deploy anti-ship and cruise missiles to its reclaimed islands in the South China Sea, with pundits decrying this move as “militarizing” the region and therefore signifying a “threat” to so-called “freedom of navigation”. Avoiding the polemical quagmire of forever arguing over the international legality of Beijing’s nine-dash line, the simple fact is that China was the strongest regional party to assertively stake out its claim, a dramatically proactive measure that stands in stark contrast to this country’s characteristic overabundance of caution.

The People’s Republic must have intensely carried out years of scenario planning before ever making its first move in the South China Sea, understanding that the process that it set into motion would be irreversible and have a global strategic impact given the importance of this waterway to the world economy and the symbolism of China going so far as to establish tangible “facts on the ground” (or rather, in this case, water) to back up its claim. Evidently, China came to the conclusion that it would be better for its long-term interests to act and risk international opprobrium than to passively sit back and let the US reclaim its regional allies’ islands and fortify them with military equipment instead.

It might seem “unfair” for the comparatively weaker countries of the South China Sea to countenance, but the only real actors that matter when it comes to this waterway are China and the US, with the remaining states leaning more closely to one or the other in helping their “patron” establish the control that they aspire to wield. Extrapolating even further, the dichotomy is essentially between the competing models of multipolar and unipolar globalization, whereby the former Chinese-led model sees Beijing attempt to reform the existing “rules of the game” to it and its partners’ advantage while the latter American-led one tries its best to retain the current system to it and its own partners’ benefit.

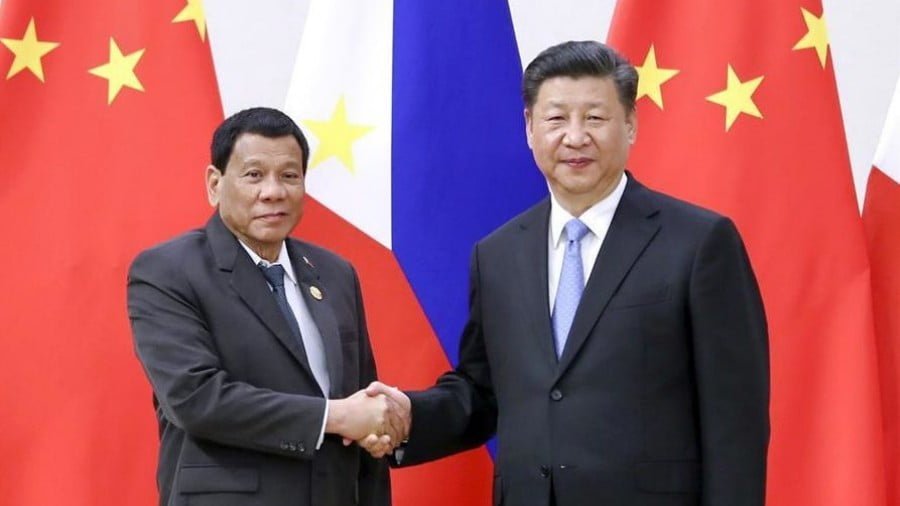

Vietnam is firmly in the American camp when it comes to the delineation of the South China Sea, whereas the US’ former colony of the Philippines has pivoted towards China ever since President Duterte came to office almost exactly two years ago. The Pentagon’s “pincer” plan to “trap” China between two weak but American-backed “Lead From Behind” claimants supported by the “Quad’s” other Indo-Japanese and Australian members has therefore failed and presented Beijing with the window of opportunity that it needed in order to break through the “containment” wall that was being built around it. It’s in this geopolitical context that it felt comfortable enough with the progress it’s made in backing up its claims to deploy state-of-the-art weaponry there.

The US and its allies are predictably fear mongering that this will somehow infringe on what they like to term as “freedom of navigation”, but the reality is that China wouldn’t “cut off its own nose to spite its face”, so to say, by interfering with maritime shipments through this route and inadvertently sabotaging its own trade networks. For that matter, Japan also wouldn’t be interested in this either, but the economic survival of the remaining three members of the “Quad” and their regional Vietnamese partner isn’t dependent on traversing the South China Sea beyond the disputed islets, hence why they’re less sensitive to any potential trade disruption here as the expected result of a forthcoming crisis.

China has proven that it’s the most powerful force in the South China Sea and has neutralized the US’ Vietnamese-Philippine “pincer” through the skillful use of Silk Road diplomacy with Manilla, meaning that Washington’s only real hope for responding to Beijing’s latest missile move in the region is to enhance its and the rest of the “Quad’s” military cooperation with Hanoi. As a prelude to this eventuality kicking into high gear, it can be anticipated that an infowar offensive will be launched in the near future in attempting to scare Vietnam into thinking that these Chinese armaments are directed against it and not the US naval assets in the area.

The “Quad” wants to formalize Vietnam’s already de-facto inclusion into this framework in order to create what could then be described as the “Quint”, but it first needs to manufacture a “publicly plausible” pretext for selling this unprecedented foreign policy realignment to the country’s public. The ASEAN state isn’t anywhere near powerful enough to challenge China on its own, hence why it would need to rely on the military expertise that only the US could realistically provide for it through a military partnership focusing mostly on naval and missile technologies. As ironic as it may be to imagine, there’s the distinct possibility that China’s missiles might one day soon be countered by American ones sold to Vietnam, but only if the infowar succeeds in making this “deal with the devil” “acceptable”.