Can China Mediate the Kachin Conflict?

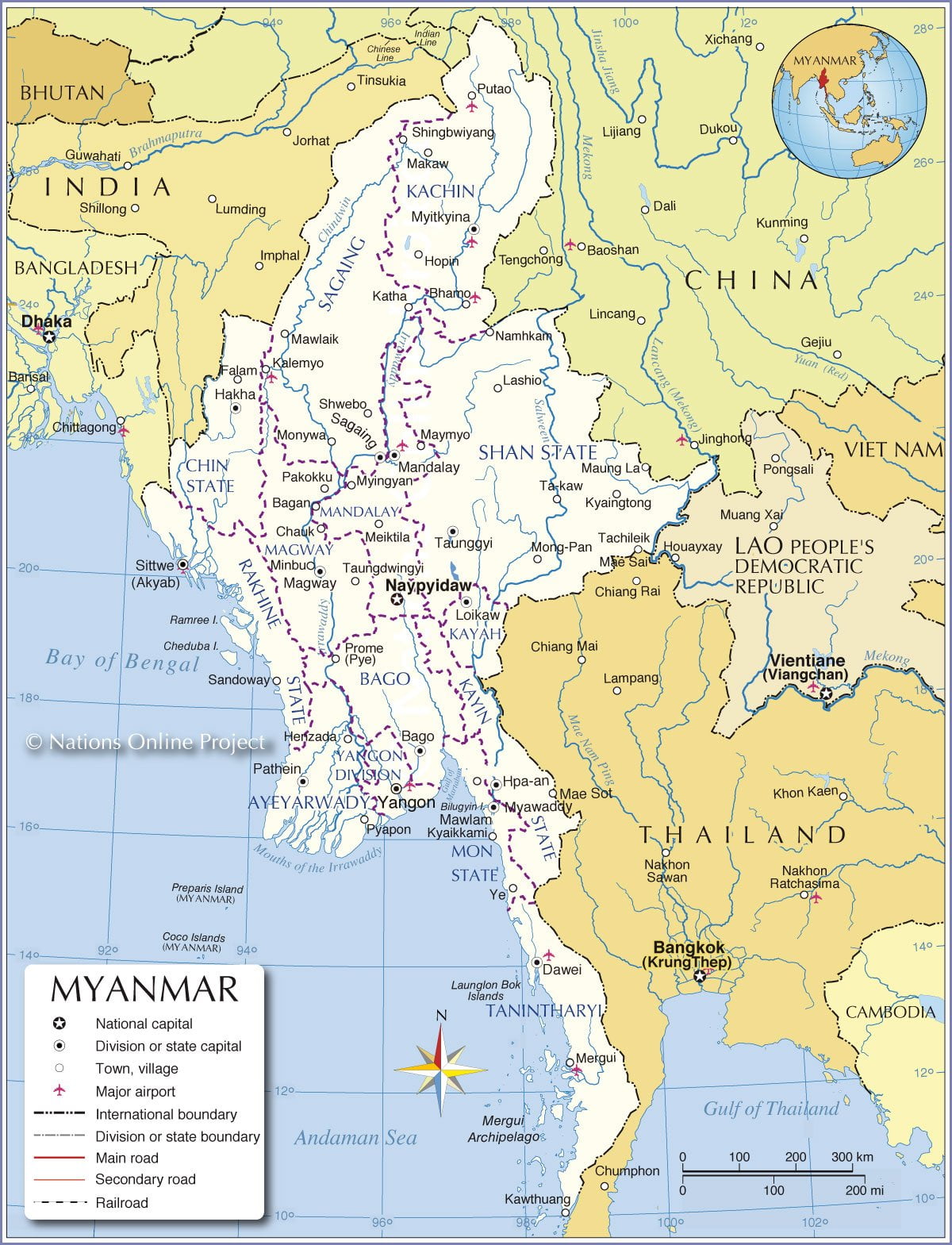

Clashes between the Myanmarese military, popularly known as the Tatmadaw, and the ethno-regional separatists of the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) in this sparsely populated but jade-rich northern region at the confluence of the country’s borders with both India and China have heated up in the past week and sent thousands of people fleeing from their homes. The latest unrest comes ahead of the third round of the Panglong Peace Conference that’s planned for later this month and which intends to make progress on “federalizing” the country as part of a “compromise solution” between the state and its myriad separatist insurgents. The Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), the political arm of its namesake army, never signed the 2015 ceasefire agreement but did take part in an earlier Panglong meeting, though it’s unclear whether they’ll participate in the upcoming one given the latest escalation.

To provide some very general context to what’s happening, Myanmar – formerly known as Burma – has been beset with ethno-regional, and to a degree, even religiously tinted violence since independence as peripheral minority groups waged separatist insurgencies against the majority-Bamar population inhabiting the heartland. The Kachin conflict is one of the oldest and pits the region’s numerically tiny Christian majority against the mighty state, but the rebels have held out for this long because the mountainous geography of their homeland pairs well with their already skillful militias. The natural resource dimension of this insurgency related to jade, timber, and hydropower has led to criticism that it might be cynically motivated by both sides’ desire to control these assets, though the driving dynamics might just be as simple as the Buddhist ethnic-majority Bamar fighting to retain their centralized state while Christian ethnic-minority Kachin rebels fight to secede.

Kachin State has roughly half the population as Rakhine State does so the humanitarian consequences of an intensified conflict will likely be less severe for its eponymous majority than for the latter’s so-called “Rohingya” minority, and moreover, neither of the region’s Indian or Chinese neighbors have any religious or ethnic links with the Kachin people unlike the Bangladeshi Muslims do with the “Rohingya”. That said, the rebels are concentrated mostly near the Chinese border, where some refugees have previously fled, and this brings about the possibility that the People’s Republic might be adversely affected if the situation doesn’t soon stabilize. That, however, could interestingly serve as a pretext for involving China as a mediator in this long-running dispute following the role that it unprecedentedly played in Rakhine State last year, and there’s a chance that it might be similarly successful in at least making temporarily superficial progress in resolving it.