Turkey’s European Dream may be Over, Is the Sultan Ready for Eurasia?

To the utter despair of stoic defenders of “Western values,” Europe is now condemned to suffer two populist autocracies on its eastern borders: Putin’s Russia and Erdogan’s Turkey.

For the EU’s political leaders, the only accepted narrative is blanket, hysterical condemnation of “illiberal democracies” distorted by personal rule, xenophobia and suppression of free speech. And that also applies to the strongmen in Hungary, Austria, Serbia, Slovakia and the Czech Republic.

These EU leaders and the institutions that support them – political parties, academia, mainstream media – simply can’t understand how and why their bubble does not reflect what voters really think and feel.

Instead, we have irrelevant intellectuals mourning the erosion of the lofty Western mission civilisatrice (civilizing mission), investing in a philosophical maelstrom of historical and even biblical references to catalog their angst.

They are terrified by so many Darth Vaders – from Putin and Erdogan to Xi and Khamenei. Instead of understanding the new remix to Arnold Toynbee’s original intuition – History is again on the move – they wallow in the mire of The West against The Rest.

They cannot possibly understand the mighty process of Eurasia reconfiguration. And that includes not being able to understand why Recep Tayipp Erdogan is so popular in Turkey.

Sultan and CEO

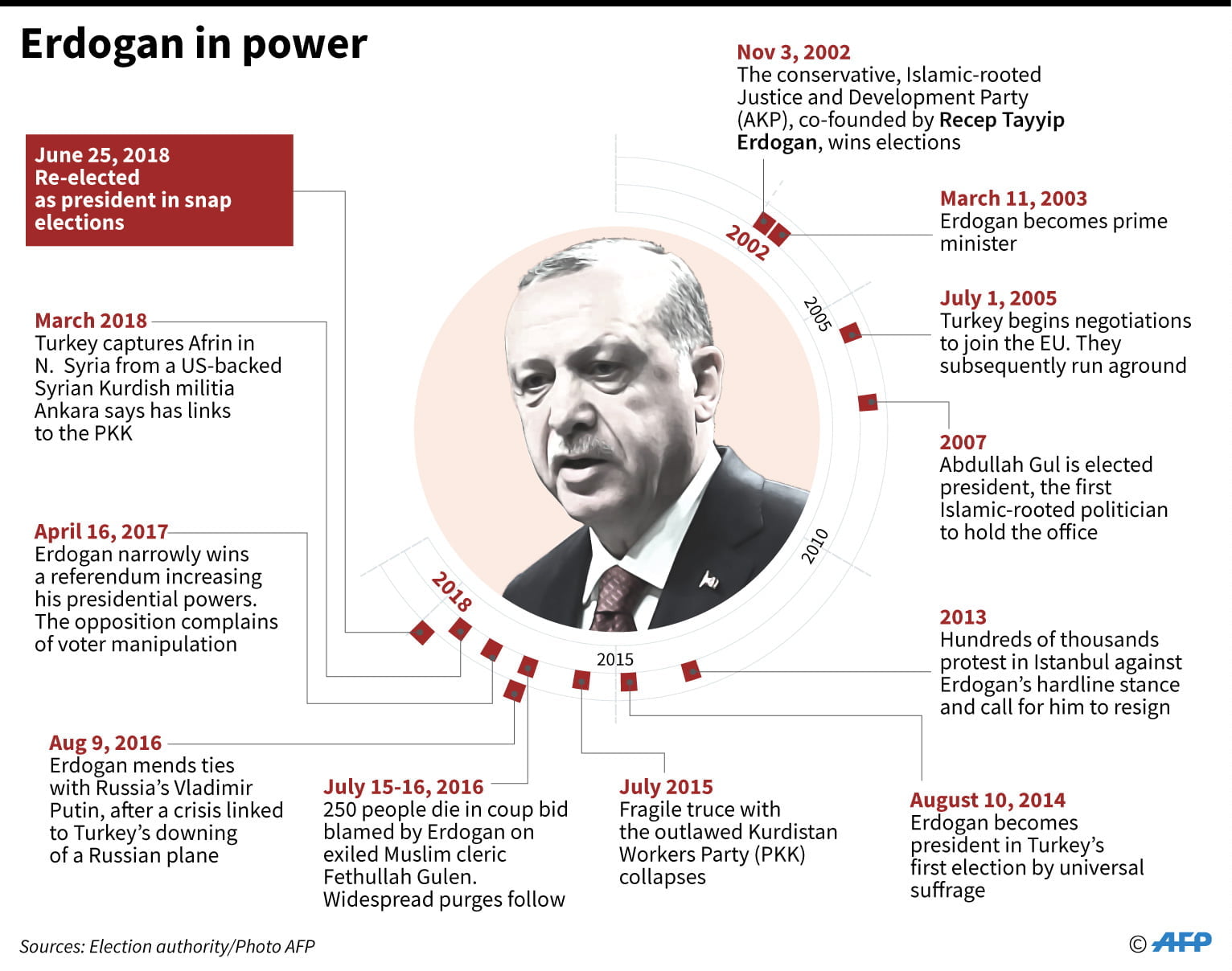

Profiting from a large turnout of up to 85% and fresh from obtaining 52.5% of the popular vote – thus preventing a run-off – Erdogan is now ready to rule Turkey as a fascinating mix of Sultan and CEO.

Under Turkey’s new presidential arrangement – an Erdogan brainchild – a prime minister is no more, a job Erdogan himself held for three terms before he was elected as president for the first time in 2014.

Erdogan may be able to rule the executive and the judiciary, but that’s far from a given in the legislature.

With 42.5% of the votes and holding 295 seats, Erdogan’s AKP, for the first time in 16 years, lost its parliamentary majority and must now establish a coalition with the far-right Nationalist Action Party (MHP).

The doomsday interpretation spells out a toxic alliance between intolerant political Islam and fascistic extreme-right – both, of course, hardcore nationalist. Reality though is slightly more nuanced.

Considering that the MHP is even more anti-Western than the AKP, the roadmap ahead, geopolitically, may point to only one direction: Eurasian integration. After all, Turkey’s perennially plagued EU accession process is bound to go nowhere; for Brussels, Erdogan is little else than an unwelcomed, illiberal, faux democrat.

In parallel, Erdogan’s neo-Ottomanism has been given a reality check with the failure of his – and former Prime Minister Davutoglu’s – Syria strategy.

The Kurdish obsession though won’t go away, especially after the success of operations ‘Euphrates Shield’ and ‘Olive Branch’ against the US-backed YPG – which Erdogan brands as an extension of the dreaded PKK. Ankara now holds the previously Kurdish-dominated Afrin, and now, under a US-Turkey deal, the YPG must also leave Manbij. Even after giving up on “Assad must go”, Ankara for all practical purposes will keep a foothold in Syria, and is invested in the Astana peace process alongside Russia and Iran.

Take it to the bridge

Turkish politics used to be a yo-yo between the center-right and the center-left, but always with the secular military as puppet masters. The religious right was always contained – as the military were terrified of its popular appeal across Anatolia.

When the AKP started its political winning streak in 2002, they were frankly pro-Europe (there was no subsequent reciprocity). The AKP also courted the Kurds, who in their absolute, rural, majority were religiously conservative. The AKP and Erdogan even allied themselves with the Gulenists. But once they solidified their electoral hold, the going got much tougher.

The turning point may have been the repression of the Gezi Park movement in 2013. And then, in 2015, the pro-Kurdish – and left-wing – Democratic Peoples’ Party (HDP) started to emerge and capture votes from the AKP. Erdogan’s response was to fashion a strategy of mingling the Democratic Peoples’ Party with the PKK – as in “terrorists,” which is absurd.

Party leaders were routinely thrown in jail. For these latest elections, HDP leader Selahattin Demirtaş actually campaigned from jail, warning: “What we are going through nowadays is only the trailer of the one-man regime. The actual scary part is yet to begin.” Even facing myriad constraints, the HDP managed to get a significant 11.7% of the vote, or 67 seats.

“One-man regime” was actually solidified a good two years ago, after Gulenists in the military ended up launching the (failed) military coup. Erdogan and the AKP leadership are convinced the Gulenists received crucial help from NATO. The subsequent purge was devastating – hitting tens of thousands of people. Anybody, anywhere, from academia to journalism, criticizing Erdogan or the ongoing dirty war in eastern Anatolia, was silenced.

Turkish historian Cam Erimtan stresses how Erdogan defended the necessity of anticipated elections by invoking “historic developments in Iraq and Syria” that have made it “paramount for Turkey to overcome uncertainty.”

Erimtan characterizes the so-called “People’s Alliance” of the AKP with the MHP as the “Turkish-Islamic Synthesis” of the 21st century, pointing how “the AKP base is large and fully convinced of the fact that the current systemic change is on the right track and that the return of Islam to Turkish public life was long overdue.”

So, “illiberal” or otherwise, the fact is a majority of Turkish voters prefer Erdogan. The European dream may be over – for good. Relations with NATO are fractious. Neo-Ottomanism is a minefield. So Eurasian integration seems the sensible way to go.

Relations with Iran are stable. Energy and military relations with Russia are paramount. Turkey can invest in economic projection across Central Asia. Russia and China are luring it into joining the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). Erdogan may finally be able to position Turkey as the essential bridge between the New Silk Roads, or Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the West.

That’s a much better deal than trying to join a club that doesn’t want you as a member. “Illiberal democracy”? Who cares?