Teaching Mandarin in Mozambique Is Good, Unless It’s for Tax Collectors

Providing foreign language lessons pro bono should always be applauded, but what China’s doing in Mozambique is controversial because it wants the host nation’s tax authorities to take the initiative in improving their relationship with its companies instead of it being the other way around with Chinese business representatives learning Portuguese in order to facilitate the fulfilment of their legal obligations in the country.

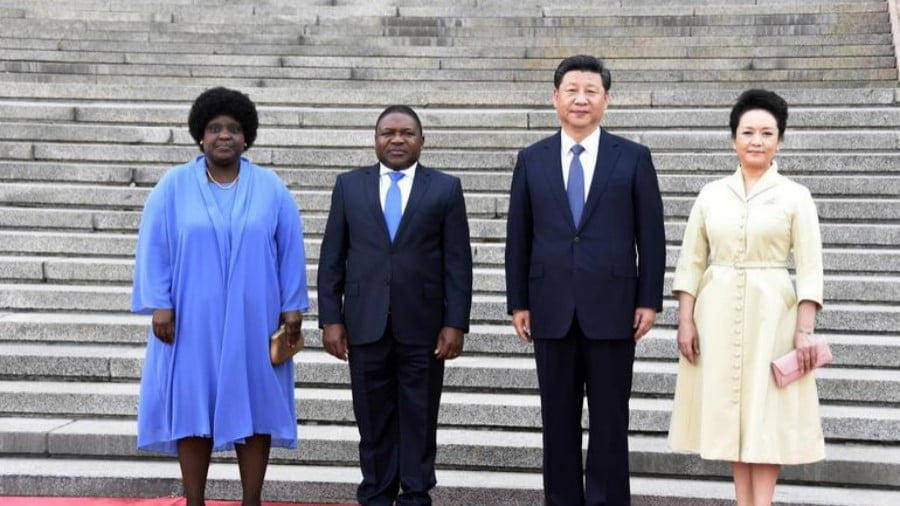

It was reported in the middle of June that around 80 employees of Mozambique’s Tax Authority started a three-month Mandarin course taught by China’s Confucius Institute, with the General Director of Common Services for this revenue-collecting body stating that the intention is “to endow the participants with communication skills in order to improve the relationship between the tax administration and taxpayers of Chinese nationality.” He then went on to say that “the great expansion of Chinese business poses challenges to the tax and customs authorities, including in communication”, drawing attention to the problem that one of the world’s poorest countries has in getting Chinese companies to fulfil their legal obligations to the host state. Regrettably, this officially confirmed state of affairs feeds into negative narratives about China’s role in Africa.

It’s long been thought, whether rightly or wrongly, that Chinese businesses often neglect the crucial socio-cultural component that’s so important in managing a company’s image in foreign countries, and it looks as though Beijing hasn’t learned this lesson when it comes to Mozambique. Instead of training some of its business representatives to speak Portuguese or hiring the needed translators from the many excellent language schools all throughout the People’s Republic, China apparently believes that the onus for facilitating cross-cultural communication and getting its companies to abide by Mozambique’s tax requirements falls on the host state and not the companies who are operating there as economic guests. Whether intentional or not, this screams of an arrogance that will ultimately be disadvantageous for China’s long-term business interests in Africa if it doesn’t change.

It’s not important in this context that China’s investments are mutually beneficial for both it and Mozambique, as the focus is on the relationship between hosts and guests. It would be slammed as “neo-imperialism” if Western companies refused to hire any Mandarin-speaking employees in their Chinese offices and instead tried to teach the national tax authorities to speak English, German, French, or whatever else, though apparently no one blinks an eye in Beijing when Chinese companies apply this very same model to Africa and specifically Mozambique. Unfortunately for the host country, it has little leverage to apply in “rebalancing” its relationship with its largest investor, therefore compelling it to play along and have its authorities learn Mandarin if they hope to reliably secure much-needed revenue for one of world’s most impoverished states.

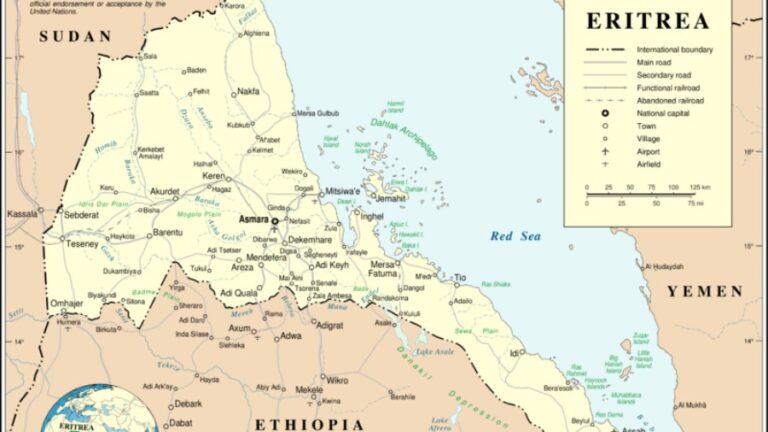

It would be amiss to project oneself onto the Mozambican authorities and speculate how they truly feel about this socio-culturally lopsided “partnership” that would be unacceptable to China if the tables were turned, but it would be understandable if some of its citizens object to the symbolism of a foreign company behaving this way inside of their country irrespective of its origins or how mutually beneficial its operations are. It’s this presumably simmering discontent that could prove to be a long-term strategic vulnerability for China and Mozambique because there’s always a chance that it could be externally exploited for Hybrid War ends, even if this is only manifested through the scenario of the RENAMO opposition politically campaigning against what it might portray as “unfair” Chinese Silk Road deals in favor of pivoting towards the Indo-Japanese “Asia-Africa Growth Corridor” instead.

In fact, sloppy socio-cultural practices by Chinese companies all throughout East and Central Africa might inadvertently result in the creation of a Western-encouraged regional zeitgeist that’s politically manipulated against the country’s interests, which is why controversies such as the one in Mozambique must be taken seriously and immediately addressed so as to nip this scenario in the bud. Economic guests anywhere in the world shouldn’t expect their host government (let alone in one of the most uneducated and chronically underdeveloped places anywhere on this planet) to speak their language if they want their taxes paid in full and on time, and the misguided policy of the guests’ country of origin teaching their language to public servants in the host state doesn’t resolve the uneven relationship created by this inadvertently condescending attitude and could actually exacerbate it.

The solution is for Chinese companies to either teach some of their in-country business representatives Portuguese before embarking for Mozambique or to bring along some of the many competent translators that the People’s Republic has surely produced out of its countless language institutions. Teaching Mozambican students Mandarin pro bono would go a long way in cultivating a future elite that could confidently interact with their Chinese counterparts one day, but this vision obviously takes time to reach fruition and won’t reap results right away. Along the same lines, it can’t possibly be expected that a three-month training course in one of the world’s most difficult languages for Western-language-proficient individuals to speak (such as the Portuguese-speaking elite of Mozambique) will lead to anything more than just parroting tax-related vocabulary for novelty’s sake.

China has the opportunity to turn what might end up being an embarrassing socio-cultural debacle into a constructive learning opportunity to demonstrate its respect of its host country’s sensitivities if it dispatches Portuguese translators to its Mozambican businesses and works out the communication differences that have hitherto been so severe that Beijing felt compelled to take the unprecedented step of having its local Confucius Institute teach Mandarin to the country’s tax collectors. The sooner that the tax-related “cultural misunderstandings” are resolved, the better it will be for China’s image in Mozambique and the rest of the Africa. As the saying goes, “it’s not the mistake that you make, but how you fix it that counts”, and this experience could therefore be put to good use for China’s future strategic planning if only the country realizes it.