A New Capital? Palestinians say Abu Dis is No Substitute for East Jerusalem

From the offputting concrete edifice that confronts a visitor to Abu Dis, the significance of this West Bank town – past and present – is not immediately obvious.

The eight metre-high grey slabs of Israel’s separation wall silently attest to a divided land and a quarter of a century of failed attempts in the Middle East peace process.

The entrance to Abu Dis could not be more disconcerting, given reports that United States President Donald Trump’s administration intends it to be the capital of a future Palestinian state, in the place of Jerusalem.

The wall, and the security cameras lining the top, are the legacy of battles for control of Jerusalem’s borders. Sections of concrete remain charred black by fires residents set years ago in the forlorn hope of weakening the structure and bringing it down.

Before the wall was erected more than a decade ago, Abu Dis had a spectacular view across the valley to Jerusalem’s Old City and the golden-topped Dome of the Rock, less than three kilometres away. It was a few minutes’ drive – or an hour’s hike – to Al Aqsa Mosque, the third holiest site in Islam, and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the reputed location of Jesus’s crucifixion.

Now, for many of the 13,000 inhabitants, Jerusalem might as well as be on another planet. They can no longer reach its holy places, markets, schools or hospitals.

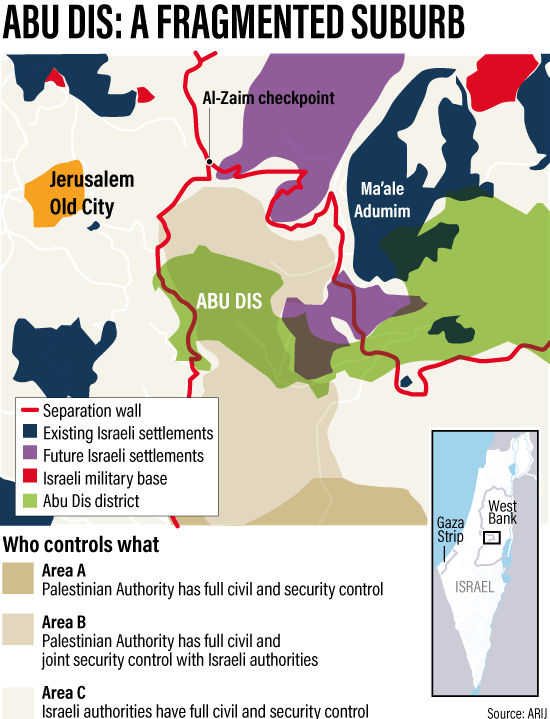

Abu Dis, say its residents, is hemmed in on all sides – by Israel’s oppressive wall; by illegal Jewish settlements encroaching relentlessly on what is left of its lands; and by a large, Israeli-run landfill site that, according to experts, is a threat to human health.

The Palestinian authorities do not even control Abu Dis. The Israeli security cameras watch over it and armoured jeeps full of Israeli soldiers make forays at will into its crowded streets.

Perhaps fittingly, given the Palestinians’ current plight, Abu Dis feels more like it is being gradually turned into one wing of a dystopian open-air prison than a capital-in-waiting.

Nonetheless, the town has been thrust into the spotlight. Rumours have intensified that Mr Trump’s promised peace plan – what he terms the “deal of the century” – is nearing completion. His son-in-law, Jared Kushner, has been drafting it for more than a year.

Back in January, Mahmoud Abbas, the Palestinian leader, confirmed for the first time that the White House was leaning on him to accept Abu Dis as the capital.

The issue has become highly charged for Palestinians since May, when Mr Trump overturned decades of diplomatic consensus by moving the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

That appeared to overturn a widely shared assumption that Israel would be required to withdraw from East Jerusalem, which it occupied in 1967, and allow the Palestinians to declare it their capital.

Instead Mr Kushner and his team appear to believe they can repackage Abu Dis, just outside the city limits, as a substitute capital.

How plausible is it that the Palestinians can accept a ghettoised, anonymous community like Abu Dis for such a pivotal role in their nation-building project?

Ghassan Khatib, a former Palestinian cabinet minister, said Mr Trump would find no takers among the Palestinian leadership.

“A Palestinian state without Jerusalem as its capital simply won’t work. It’s not credible,” he said. “It’s not just Jerusalem’s religious and historic significance. It also has strategic, economic and geographic importance to Palestinians.”

The people of Abu Dis appear to feel the same way, with many pointing to Jerusalem’s enormous symbolic power, as well as the potential role of international tourism in developing the Palestinian economy.

Abu Dis, however, is unlikely ever to attract vistors, even should it get a dramatic makeover.

The approach road, skirting the settlement of Maale Adumim, home to 40,000 Jews, is adorned with red signs warning that it is dangerous for Israelis to enter the area.

The section of wall at the entrance to Abu Dis alludes to residents’ growing anger and frustration – not only with Israel but some of their own leaders.

Artists have spray-painted a giant image of Marwan Barghouti, a Palestinian resistance leader imprisoned by Israel for the past 16 years. It shows him lifting his handcuffed hands to make a V-for-victory sign.

But noticeably, next to him is a much smaller image of Mr Abbas, president of the Palestinian Authority, whose face has been painted out. He has come under mounting domestic criticism for maintaining Palestinian “security co-operation” with Israel’s occupation forces.

Resentment at such co-operation is felt especially keenly in Abu Dis. Large iron gates in the wall give the Israeli army ready access in and out of the town.

Under the Oslo accords signed in the mid-1990s, all of Abu Dis was placed temporarily under Israeli military control and most of it under civil control too. That temporary status appears to have become permanent, leaving residents at the whim of hostile Israeli authorities who deny building permits and readily issue demolition orders.

The restrictions mean Abu Dis lacks most of the infrastructure one would associate with a city, let alone a capital.

Abdulwahab Sabbah, a community activist, said: “We are now a small island of territory controlled by the Israeli army.

“Not only have we lost our schools, the hospitals we once used, our holy places, the job opportunities that the city offered. Families have been split apart too, unable to visit their relatives in Jerusalem.

“We have been orphaned. We have lost Jerusalem, our mother.”

A short drive into Abu Dis and the shell of a huge building comes into view, a reminder that the idea of an Abu Dis upgrade is not the Trump administration’s alone.

In fact, noted Mr Khatib, Israel began rebranding Abu Dis as a second “Al Quds” – the Holy City, the Arabic name for Jerusalem – in the late 1990s, after the Oslo agreement allowed Palestinian leaders to return to Gaza and limited parts of the West Bank.

The Palestinian leadership, desperate to get a foothold closer to the densely populated neighbourhoods of East Jerusalem, played along. They expected that Israel would eventually relinquish Abu Dis to full Palestinian control, allowing it to be annexed to East Jerusalem in a future peace deal.

In 1996, the Palestinians began work on building a US$4 million (Dh14.69m) parliament on the side of Abu Dis closest to Jerusalem. The location was selected so that the office of the late Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat would have a view of Al Aqsa.

Reports from that time talk of Abu Dis becoming a gateway, or “safe corridor”, for West Bank Palestinians to reach the mosque. One proposal was to build a tunnel between Abu Dis and the Old City.

However, with the outbreak of hostilities in 2000 – a Palestinian intifada – work on the parliament came to a halt. The interior was never finished, and there is now no view of Al Aqsa. The parliament too is sealed off from Jerusalem by the wall.

Since then, Israel has barred the Palestinian Authority from having any role in East Jerusalem.

Khalil Erekat, a caretaker, holds the key to the unused parliament. Once visitors could inspect the building, including its glass-domed central chamber. Now, he said, only pigeons and the odd stray dog or snake ventured inside.

“No one comes any more,” he added. “The place has been forgotten.”

And that, it seems, is the way Palestinian officials would prefer it. With the Trump administration mooting the town as a substitute capital, the parliament is now an embarrassing white elephant.

Requests from The National to the Palestinian authorities to visit the building were rejected on the grounds that it was no longer structurally safe.

Evidence of how quickly Israel has transformed Abu Dis from a rural suburb of Jerusalem into an eyesore ghetto are evident in the homes around the parliament.

A once-palatial four-storey home next door would be more at place in war-ravaged Gaza than an impending capital. Its collapsed top floors sit precariously above the rest of the structure.

Mohammed Anati, a 64-year-old retired carpenter, is a tenant occupying the bottom floor with his wife and three sons.

He said the destruction was carried out by the Jerusalem municipality several years ago, apparently because the upper floors were built in violation of planning rules that Israeli military authorities imposed after 1967.

Neighbours speculate that, in fact, Israel was more concerned that the top of the building provided views over the wall.

Mr Anati said that, paradoxically, the Jerusalem municipality treated this small neighbourhood next to the wall as within its jurisdiction.

“We have to pay council taxes to Jerusalem even though we are cut off from the city and receive no services,” he said.

Asked whether he thought Abu Dis could be a Palestinian capital, Mr Anati scoffed. “Trump will offer us the worst deal of the century,” he said. “Jerusalem has to be the capital. There is nothing of Jerusalem here since Israel built the wall.”

Nearby, Ghassan Abu Hillel’s two-storey home presses up against the grey slabs of concrete. He says cameras on the top of the wall monitor his and his neighbours’ activities around the clock.

His family moved to this house in 1967, when he was 14 years old, and shortly before Israel occupied Abu Dis, along with the rest of the West Bank and East Jerusalem.

Until the wall was constructed, he spent his time herding sheep and goats on the surrounding hills.

Now he has had to corral then into a corner of the wall. Their improvised pen is daubed with graffiti: “Take an axe to the prison wall. Escape.”

His herd of what was once more than 200 sheep is now down to barely a dozen. The animals can no longer graze out on the hills, and he cannot afford the cost of feeding them straw.

Unlike Mr Abu Hillel and his sheep, his pigeons still enjoy their freedom. “They can fly over the wall and reach Jerusalem whenever they want,” he said.

His family owned much of the land surrounding Abu Dis before 1967, he said, but almost all of it was taken by Israel – originally on the pretext that it was needed for military purposes.

Since then, Israel has built a series of Jewish settlements on the surrounding land, including Maale Adumim, Kfar Adumim and Kedar.

In the early 1980s, it also opened a landfill site to cope with the region’s waste. In 2009 the United Nations warned that toxic fumes from waste-burning and leakage into the groundwater posed a threat to local inhabitants’ health.

Some residents are actively finding ways to break out of the isolation imposed on Abu Dis by Israel.

Mr Sabbah is a founder of the Friendship Association, which encourages exchange programmes with European students, teachers and youth clubs. His most successful project is the twinning of Abu Dis with the London borough of Camden.

Mr Sabbah’s prominent political activities may be one reason why his home – along with the local mayor’s – was one of 10 invaded in the middle of the night on September 4.

The operation had the hallmarks of what former Israeli soldiers from the whistleblowing group Breaking the Silence have termed “establishing presence” – military training exercises designed to disrupt the lives of Palestinian communities and spread fear.

Mr Sabbah is sceptical that the Abu Dis proposal by the Trump administration has been made in good faith.

“It’s a bluff,” he said. “Israel has shown through all its actions that it does not want any Palestinian state – and that means no capital, even in Abu Dis.

“It is being offered only because Israel knows no Palestinian leader could ever accept it as a capital. And that way Israel can again blame us for being the ones to reject their version of ‘peace’.”

Amid its confinement, however, Abu Dis does have one asset – a university – that now attracts thousands of young Palestinians, although it adds to overcrowding.

The main campus of the Palestinian-run Al Quds University has been operating in Abu Dis since the 1980s.

Sitting on the crossroads between the Palestinian cities of Bethlehem and Nablus to the south, Jericho to the east, and Ramallah to the north, the Abu Dis campus has grown rapidly. It has profited from the fact that West Bank Palestinians cannot access another campus of Al Quds University in East Jerusalem.

The university is enclosed and security is tight. Inside, students enjoy spacious grounds with shaded gardens, a small oasis of normality where it is possible briefly to forget the situation outside.

The university is not immune from Israeli military operations either, however. On September 5, soldiers shut down the campus and nearby schools, as they reportedly fired tear gas, stun grenades and rubber bullets at youths.

Omar Mahmoud, aged 23, a medical student from Nablus, raised his eyebrows at the suggestion that Abu Dis could serve as the Palestinians’ capital.

“It’s fully under Israeli control,” he said. “One side there is the wall and on the other side there are Israeli settlements. There are no services and it just gets more crowded by the year.”

He has shared an apartment with other students in Abu Dis for five years. He said: “To be honest, I can’t wait to get out of here.”