New Satellites Will Use Radio Waves to Spy on Ships and Planes

When a company called HawkEye 360 wanted to test its wares, it gave an employee a strange, deceptive task. While the worker stood in Virginia, he held the kind of transceiver that ships carry to broadcast their GPS locations. Usually such a signal would reveal his true position to a radio receiver, but he’d altered the broadcast to spoof his GPS position, making it seem like he was in fact off the coast of Maine.

But his company’s instruments, which in this test were carried by Cessnas flying routes over East Coast waters, picked up on the chicanery. Now HawkEye 360, the satellite startup that made the detectors, plans to send its first three instruments into space later this month. Called Pathfinder, the cluster of satellites will work together to locate and make sense of radio emissions beamed up from the ground. With it, HawkEye 360 gains access to communications information that has mostly been controlled by governments.

Lots of companies have launched, or hope to launch, satellites that snap pictures of Earth. But HawkEye 360 wanted to do something different: scan the planet for its radio-frequency signals instead. That kind of intelligence has mostly been the domain of militaries and intelligence agencies. But with ever-cheaper and simpler radio technology, and the relative ease of building small satellites, the time seemed right for private industry to give it a shot.

The company began after Chris DeMay, an expert in radio frequencies who’d spent 14 years working in the intelligence community, attended a conference called SmallSat a few years ago. He saw all of those picture-taking satellite companies, and realized that the invisible part of the electromagnetic spectrum could also be used to monitor the Earth.

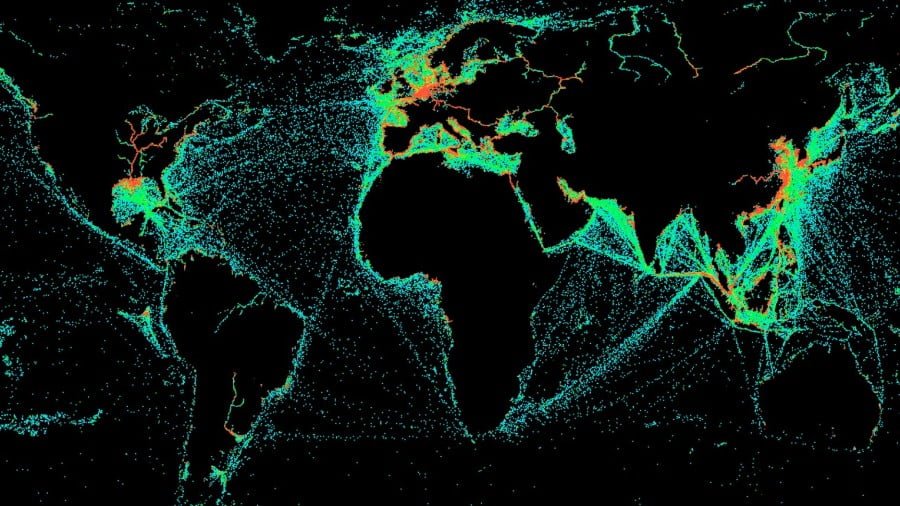

Radio waves come from ships, planes, battlefields, search-and-rescue operations, cell towers, and basically anything that needs to communicate with another thing. These waves reveal the things’ locations and their character. Ever more crowded, this spectrum is full of interference and crosstalk. Maybe a new fleet of satellites could help clear the air, DeMay thought, and understand what was whipping through it unseen, and from where.

HawkEye 360’s first three satellites will fly in formation around 350 miles above Earth, using tiny thrusters to keep their position relative to one another stable. On board, they will each carry a receiver that collects radio waves coming from Earth—any transmission more powerful than a watt—and then sends information about those waves down to a station on the ground.

Some customers, of which HawkEye 360 currently has 10 in the government sector, are just interested in that data, straight up. Others, though, want a little more hand-holding. For them, HawkEye 360 plans to offer more specialized support, answering such questions as, “Whose communications are messing with mine?”

“Our strategy is focused primarily on the US government today,” says John Serafini, HawkEye’s CEO. With its advisers having done time in the CIA, the NSA, and various defense-related agencies, the company’s initial strategy seems likely to tilt toward spycraft. It also has a deal with Raytheon, a large defense contractor and one of its main investors, to feed HawkEye data and analysis into Raytheon’s own systems.

At first, HawkEye 360 will focus on the high seas: illegal fishing, drug trafficking, human trafficking, weapons trafficking. “That takes place in the open ocean where people think they’re unseen,” says DeMay. If a ship spoofs its location or identity, HawkEye 360 believes its birds will be able to detect that. A 2013 report estimated that such spoofing had increased by 59 percent in the two years before. More recently, ships in the Black Sea were subject to spoofing from the outside; someone else had scrambled their locations. On top of spotting such spoofs, HawkEye 360’s analytics could identify a target’s rendezvous with relay ships—even if both are “dark.” “We can detect signals it didn’t realize it was transmitting,” says DeMay.

After the company picks up different signals from a ship (or a plane), it’s got its fingerprint. “We can…track it into perpetuity,” says Serafini.

The satellites should also be able to pinpoint distress signals, and, in a disaster, figure out which wireless communications are still working. HawkEye 360 also plans to thrust itself into “spectrum allocation,” or watching who’s using which frequencies, almost in real-time. That kind of monitoring could eventually make spectrum use more on-the-fly (the topic of an ongoing Darpa program): People could pop into bands when they’re silent, not just stare longingly at them.

Later this month, HawkEye 360’s three small satellites are booked to ship out for space on a bigger launch that’s been dubbed the SmallSat Express. The mere existence of the launch speaks to the space industry’s hawkishness on small satellites. While little satellites normally have to nestle in, as second-class citizens, among bigger orbiters (or book specialized space on a small rocket), a company called Spaceflight Industries bought out the entire payload of one of SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rockets and gathered 60-some satellite passengers for a clown-car rideshare. Currently slated to launch on November 19, these dozens of satellites will take the ride of their lives together, shaking and pulling big Gs until they get to space. Then they will cut loose, disperse to their desired orbits, to see if they can do the big jobs for which they were built.

Reblogged this on Rangitikei Enviromental Health Watch.