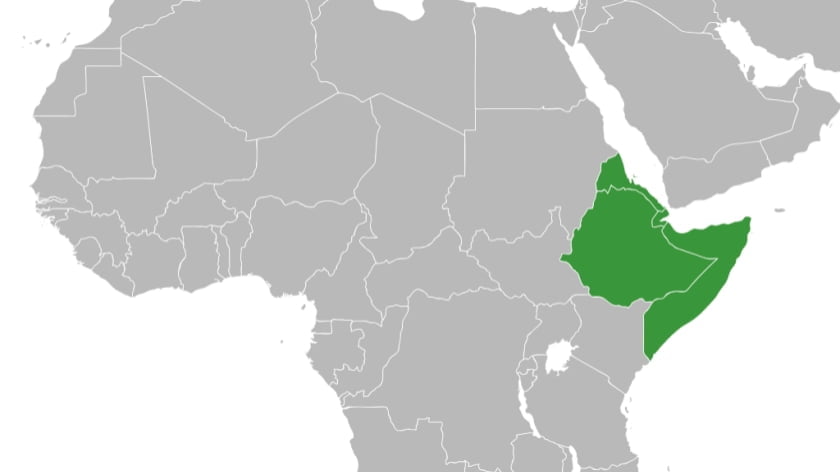

Who’s Right And Who’s Wrong In The Kenyan-Somalian Maritime Dispute?

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) is hearing Kenya and Somalia’s cases pertaining to their ongoing maritime dispute from 9-13 September, and it’s worthwhile contemplating which side is right.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) is the international agreement that practically all of the world abides by for determining maritime borders and the actions that other states can carry out within them, and it’s front and center in the cases that the International Court of Justice (ICJ) is hearing from Kenya and Somalia from 9-13 September about their ongoing maritime dispute. The Africa Report published a very informative run-down of the situation last month that’s a must-read for anyone interested in getting caught up on this issue, especially since the facts contained therein strongly point to which side is in the right and which one is in the wrong. The outlet confirmed that the core issue at play is the offshore energy resources in this disputed maritime triangle whose blocs are being auctioned off to foreign investors, which could understandably result in a windfall of revenue for whichever of the two states it is that’s found to have legitimate rights to the riches under those waters.

The article goes on to list a few of the most important relevant developments that have occurred in Kenyan-Somalian relations over the past year, including the first-mentioned recalling its Ambassador from Mogadishu, expelling the Somalian one from Nairobi, and recently suspending direct flights between their capitals. Somalia’s response pales in comparison since it only said that its officials won’t attend any meetings in Nairobi any longer and also banned Kenyan NGOs from working in the country. Kenya’s indisputably disproportionate response to Somalia taking this issue up with the ICJ is probably due to its expectation that the global body will rule that the two neighboring states should divide the disputed waters in the middle, an outcome that might have been avoided had Somalia succumbed to Kenyan pressure and relied on regional integration organizations such as the East African Community (EAC), the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), and the African Union (AU) that might have favored Nairobi instead for their respective self-interested regions.

Kenya hasn’t publicly accounted for why it’s reacting in such a way, but it might be that some of its decision makers believe that Somalia “owes” it all of the disputed maritime territory in exchange for the anti-terrorist services that it’s carried out in the neighboring country over the years. About those, they’re actually very controversial among some Somalians who believe that Kenya is behaving imperialistically and carrying out human rights abuses as well. On top of that, Somalian nationalists regard the eastern part of Kenya as historically belonging to their people and only being included in the former as a result of arbitrary British administrative decisions, which makes them all the more enraged that Kenya is behaving so aggressively in trying to pressure their country into complying with its demands to give up the case and abandon their claims to the disputed territory. So far is Kenya going in its campaign of pressure against Somalia that The Africa Report concludes its article by worrying about the implications that this could have on regional security.

The author Morris Kiruga ominously concluded with the passage that “Bottom line: For Somalia, a win at the ICJ would be a diplomatic coup. However, without the support of its economically and militarily bigger neighbour, especially as al-Shabaab escalates its attacks on Mogadishu, it would be a Pyrrhic victory”, which hints that Nairobi might withhold much-needed economic and even military assistance to its neighbor as revenge for a negative verdict by the ICJ. This scenario is extremely disturbing but can’t be ruled out since potentially billions of dollars could be on the line with the court’s decision, and the government’s standing among its people might drop if anti-government populists run with the narrative that “Kenya capitulated to Somalia” of all countries by respecting the court’s unenforceable decision. It’s for that reason why it can be expected that Kenya might not go along with the court’s possible ruling that it evenly divide the territory with Somalia, instead resorting to “gunboat diplomacy” to establish so-called “facts on/under the water” along with cutting off its economic and military aid as de-facto sanctions against its neighbor.

If that happens, then Somalia will be hard-pressed to pursue its claims since the country is already struggling to establish sovereignty within its own mainland borders, to say nothing of beyond them in the maritime realm. On top of that, Kenya is one of its most important economic partners, so being cut off from it as vengeance for the prospective decision in partial support of Somalia’s claims could hamper its post-war reconstruction. In addition, in the unlikely scenario that Al-Shabaab regains its mid-2000s strength and poses another existential threat to the state, then Mogadishu might not be able to rely on Nairobi for help if it desperately needs it. As such, the only realistic recourse that Somalia would have in that case would be to draw as much attention as possible to Kenya’s predicted eschewing of the ICJ’s decision in order to frame its expected actions in the worst way possible as a form of HybridWar against a struggling state. That might not lead to any tangible consequences for Kenya, but it might be the intangible soft power ones that ultimately matter in the long term.

By Andrew Korybko

Source: Eurasia Future