Erdogan and Putin: The End of the Affair

Traditionally, there are two danger zones for Russian foreign policy.

The first is when Russia is too weak and the West dismisses its national interest as irrelevant. This lasted for the first two decades in the life of the Russian Federation. It began with the Kosovo war, Nato’s eastern expansion, the US decision to withdraw from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in 2001 and its decision to topple Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi.

Successive US presidents – Bill Clinton, George Bush and Barack Obama – mouthed interest in Russia but dismissed it as a poor nation struggling to come to terms with loss of empire. “We hear what you say, but we are going to do what we want anyway,” went the collective mantra from the White House.

Western exceptionalism ended with the Russian interventions in the Ukraine in 2014, Crimea and Syria.

But the second danger zone is when Moscow itself overestimates its ability to stamp its will on foreign nations. When it, too, shows the arrogance of which it has genuinely been victim. This has now began to happen in Syria.

The pendulum does not stay long in either zone.

‘Brilliant achievements’

Russian foreign policy analysts who enjoy the protection of, and access to, the Kremlin ended the last decade on a high.

Successive US presidents mouthed interest in Russia but dismissed it as a poor nation struggling to come to terms with loss of empire

A good example was Sergei Karaganov’s analysis in Rossiyskaya Gazetta. Karaganov listed the following “brilliant achievements” of the last decade: halting the expansion of western alliances; stopping in Syria a series of imposed colour revolutions that destroyed entire regions (by which he meant the Arab Spring); gaining advantageous trade positions in the Middle East; cultivating China as an ally; changing the balance of power with Europe in its own favour.

Even less hawkish Russian foreign policy hands like Dmitri Trenin, director of the Carnegie Center in Moscow, tweeted recently: “Neither Turkey nor Russia is itching for a fight with the other in/over Syria. Official rhetoric in Moscow is about conflict prevention. Yet the Russian military probably agree that Turkish forces had to be given a powerful signal that they had gone too far.”

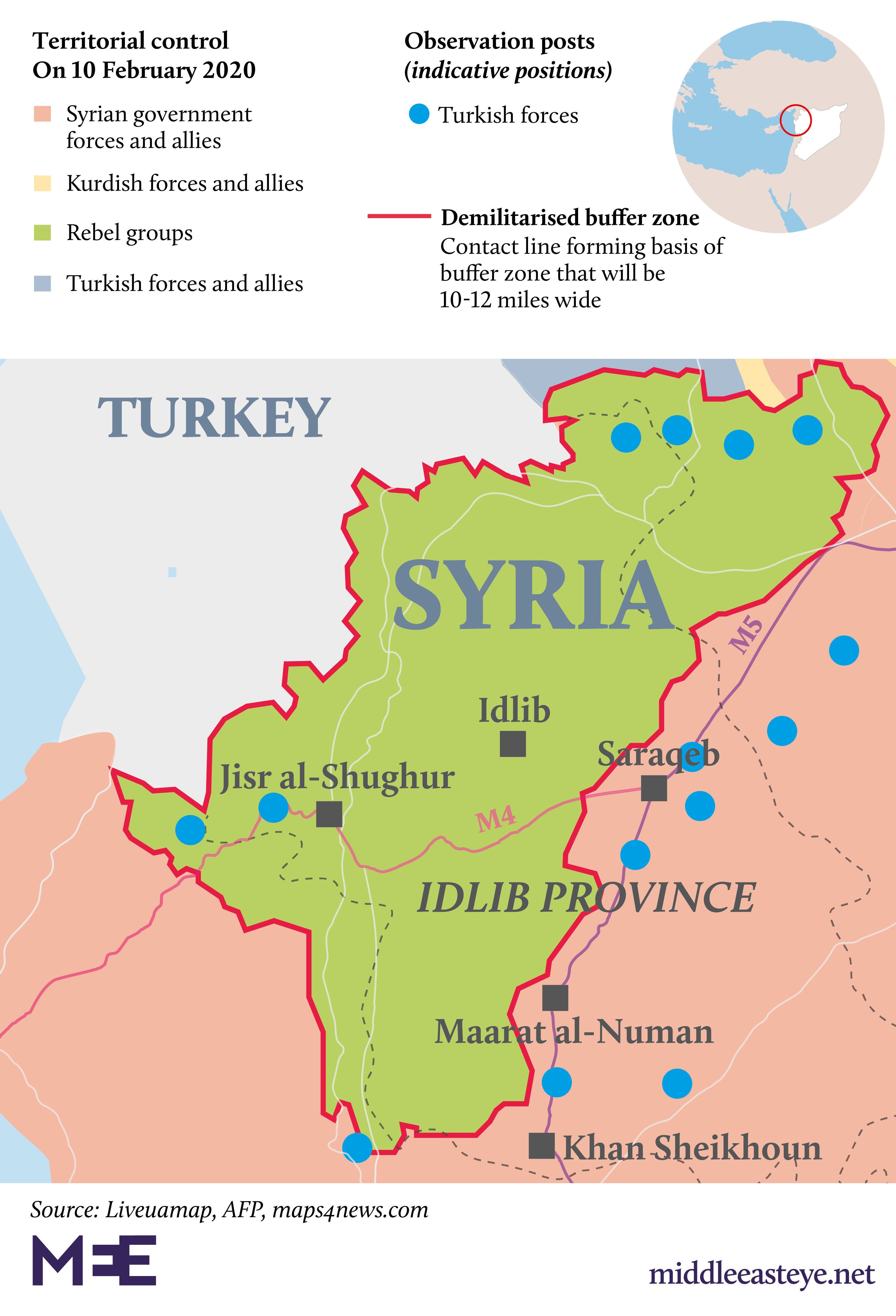

The “powerful signal” that Trenin referred to was an attack on a Turkish military convoy which killed at least 34 soldiers and wounded many more in Idlib.

The strike on the convoy, which the Russia military commanders blamed on Turkey, both for its continued artillery strikes and for not telling them in advance where Turkish troops were going, was a clear misreading of both the Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s mentality and his precarious political situation at home.

The blossoming relationship

To deal with the latter first. From the start Erdogan’s love affair with Vladimir Putin, which began when Moscow sent him the billets doux he was not getting from Washington after the abortive coup in July 2016, had strict limits.

From the start Erdogan’s love affair with Vladimir Putin had strict limits

Erdogan would walk the walk with Moscow – opening Turkstream, a pipeline carrying natural gas from Russia to southern Europe bypassing Ukraine; buying Russian S-400 air defence missiles at the cost of losing US stealth fighters – just as long as those moves provided Turkey leverage with Washington or allowed him to do more in Syria than was possible when he was still toeing the western line.

In Syria, Turkey’s blossoming relationship with Russia involved uncomfortable trade-offs – in which each side abandoned an ally. For Russia it was the Kurds of the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) and for Ankara it was the Syrians of East Aleppo.

But the fruit of that relationship was always going to be date stamped for one very simple demographic reason. With each victory scored by the Syrian regime, the number of Syrian refugees in Idlib swelled. Four million of them are currently trapped in an area the size of Somerset and 900,000 of them have fled to the Turkish border. This is the largest single displacement of refugees in the whole of the war. Its passed largely unnoticed in Europe, until now.

Erdogan cornered

With 3.6 million registered Syrian refugees in Turkey, a resurgent Kemalist opposition that has seized control of the two major cities Istanbul and Ankara in the last elections and openly expresses hostility to the refugees, coupled with the splitting of his own conservative Islamist party base, Erdogan was cornered.

What Assad was doing to the refugees was rapidly becoming an existential political threat to Erdogan as president

He could not let both Bashar al-Assad and Putin drive another mass wave of Syrians towards his borders. Erdogan had to act. What Assad was doing to the refugees was rapidly becoming an existential political threat to Erdogan as president.

Secondly, there is Erdogan’s mentality. Erdogan thinks of his place in Turkey’s history very much as Putin thinks of his in Russian Christian Orthodox history. Or for that matter Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu does in Jewish history.

None of these men consider their leadership temporary, or subject wholly to the popular will in free elections. Each of them think of themselves as men of destiny, anointed by God to fulfil not just their own aspirations but their nation’s.

The Turkish military advances over the weekend surprised the Russians. Their commentators became visibly more hesitant in interviews with Arab-speaking media.

The pounding that Turkish drones and its artillery were giving Assad’s army achieved three objectives: they knocked out a chemical factory making chlorine, two airports including Nairab west of Aleppo, and an impressive number of tanks, armoured personnel carriers and guns.

The combat effectiveness of Turkish forces in Idlib, particularly the performance of its drones, amply justified the analysis of Mossad’s director Yossi Cohen, whom I reported this time last year, as attending a secret meeting in Riyadh. Cohen told the meeting that while Iran could be contained militarily, Turkey had far greater capability: “Iranian power is fragile. The real threat comes from Turkey,” he said, according to witnesses.

End of the affair?

The result was the end of the affair between Erdogan and Putin. Their phone call this weekend was a shouting match. Erdogan told Putin to get out of the way of his forces, and Putin told Erdogan to get out of Idlib. This was the first time that either man had used this sort of language privately to each other, language they usually reserved towards western heads of state.

Very soon the Turkish media lost its awe for Russian officials and the Russian influence over senior Turkish officials expired too. For much of the last few years Russia gained a reputation of keeping its promises. All that has gone.

A new realism has set in in Ankara about Russia’s willingness to keep to the promises it made to Turkey in Sochi and this means that Erdogan will strike a harder bargain when he goes to Moscow.

It’s impossible to predict what either Putin or Erdogan will achieve. Officially Moscow’s line is all about further conflict prevention, while of course doing the exact opposite on the ground in Idlib.

But the new element in these calculations is two regional powers on opposite sides of the conflict willing – and able – to use force. Russia is no longer the only foreign army in northern Syria willing to fight – and here I continue to discount the presence of US troops in Syria’s north east.

Far from over

Syria’s front lines remain highly volatile. And this conflict is far from over, no matter how many times Putin has declared “mission accomplished”. Both Russia and Turkey can do each other’s forces mischief, while at the same time not hitting each other directly.

For Erdogan the stakes have risen again and with it his rhetoric. He said on Sunday: “Turkey is waging a historic and decisive struggle for its present and its future. We continue to work tirelessly night and day for the achievement of a victory that will safeguard the interests of our country and our nation and that will yield significant outcomes similar to those we witnessed a hundred years ago.”

“We realise that if we evade the struggle in this geographic zone that has been the subject of occupation and oppression throughout history and if we do not adhere to our unity and solidarity, we shall have to pay a much bigger price.”

This no less is an allusion to Ataturk’s successful defeat of allied landings at Gallipoli a century ago, when Turkey was on the point of being dismembered by allied powers had they won. Their defeat paved the way for the rise of Ataturk and resurgent Turkish nationalism.

The new order

Erdogan is now thinking the same about his campaign in Syria where he is facing a number of foreign armies.

If he wins this round, he will have established for Turkey a bigger say not just at the table with Russia, but in the region too. Turkey’s enhanced role in Syria would also affect the balance of power in the Sunni Arab world facing Iranian over-expansion in Arab lands.

Which is why Israel identified Turkey, a former military ally to whom it sold drones, as a bigger military threat than Iran, now that Turkey makes its own drones, and why social media in Saudi Arabia and the UAE gloated over the number of Turkish casualties in Idlib.

Erdogan is playing for high stakes. Putin, too, must be calculating the costs of his “success” in Syria, which are growing year on year, in a land in which reconstruction is decades away.

Russian military force in Syria only worked when there was no real opposing military force that could shoot its jets down. Now there is. Much hinges on this contest.

Welcome to the new “multilateral” post-western world order, which is just as unstable as the western-dominated order it replaced.

By David Hearst

Source: Middle East Eye