How Mohammed bin Salman’s Biggest Gamble May Cost Him the Throne

For much of its existence, Saudi Arabia was stable.

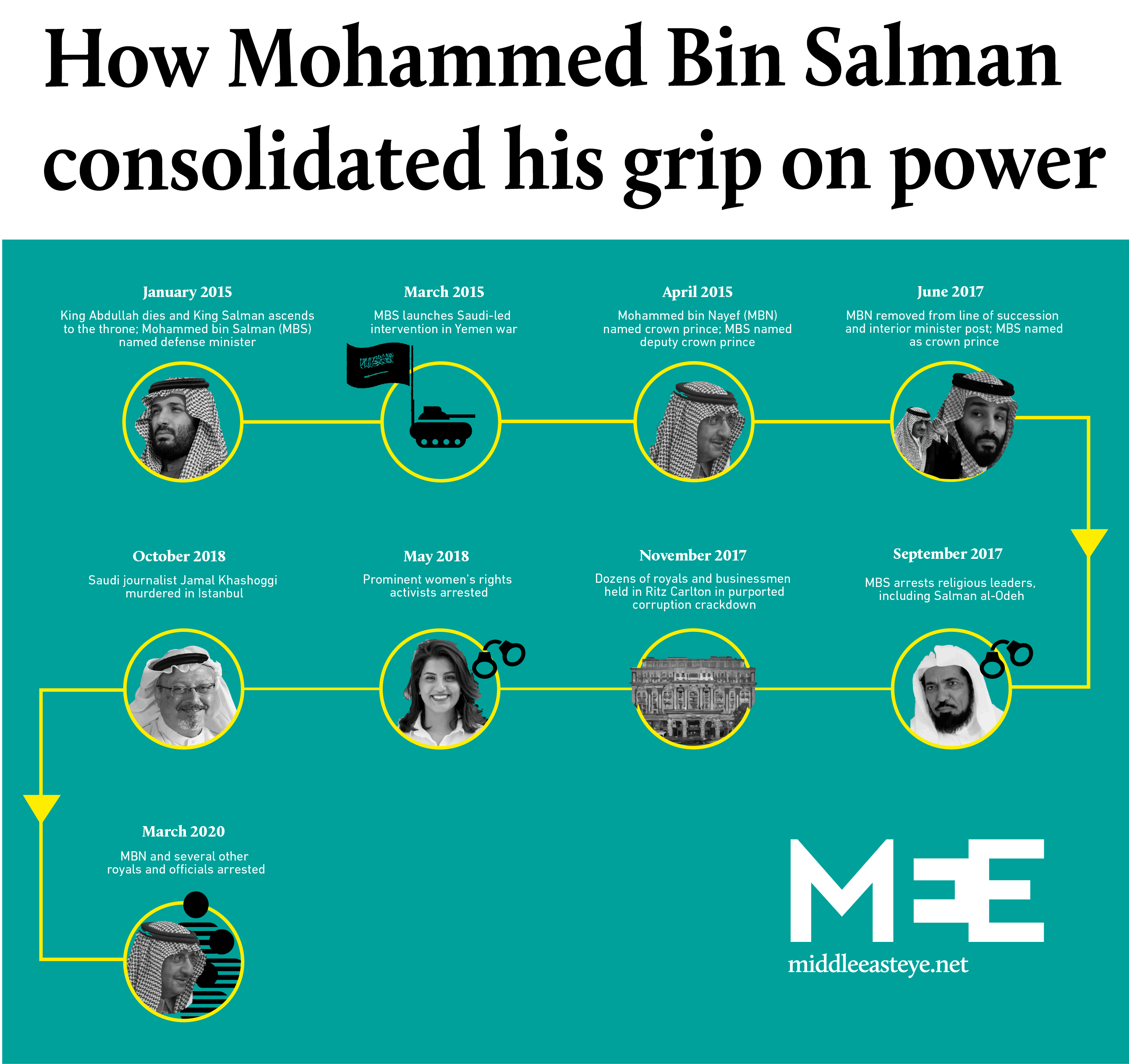

It was an absolute monarchy which dealt with dissidents ruthlessly. Arbitrary detention, torture, disappearances at home and kidnappings abroad were its staple diet. Wahhabism was used as a brutal method of religious and social control. Kings bought popularity by handouts such as paying for degrees abroad. This is how the kingdom functioned – for decades – with relatively few internal problems. EXCLUSIVE: Saudi crown prince plans to become king before November G20 summit Read More »

It was ruled by a council of princes, sons of its founder King Abdulaziz, who shared the goodies out among themselves, ensuring that each branch was represented: the Nayefs got the interior ministry, the Sultans the defence ministry, the Abdullahs the National Guard, the Faisals the foreign ministry and the Talals the media, and so on.

Lucrative ministerial portfolios were handed down from father to son like the family silver and in that way expertise and experience were accrued and kept within the family.

Fierce rivalries

When crises struck, collective decisions were taken. A family council was convened and decisions were taken slowly and with great, almost excessive, caution. Saudi foreign policy, it was said, was conducted behind bead curtains, it was that inscrutable. The kingdom was wholly in the service of US military and oil interests in the Gulf, but within that large rubric, it had its own agendas.

For all the Saudi internal clan tensions, there was stability

There were succession disputes to compare with what happened this week, such as when Crown Prince Faisal challenged the authority of King Saud in the 1960s. But these were swiftly and quietly resolved. When Saud lost that power struggle and was forced to fly off into exile, he was waved goodbye at the airport by his ouster.

There were also fierce rivalries. The murdered Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi was a supporter of Mohammed bin Nayef who ruled the interior ministry with an iron fist, imprisoning and executing hundreds, but the same could not be said of Prince Ahmed bin Abdulaziz, who released prisoners when he took over the same post.

Khashoggi never tired of saying that there was no difference between Prince Ahmed and his nephew Mohammed bin Nayef, save that one was crown prince and the other not. I remember thinking this was overly harsh.

But for all the internal clan tensions, there was stability.

No more. This period has passed. Look at how violently the Saudi royal yacht has been rocking and this list is the work of just the last few days.

Hasty decisions

A purge has been launched against a brother of the king and son of the founder Abdulaziz, considered, until now, untouchable; the Houthis overran cities in the Khub Walshaaf district on the border with Saudi Arabia, before being pushed back on Monday; the borders of the country have been closed, Umrah pilgrimage to Mecca stopped only six weeks before the start of Ramadan and the Eastern Province closed down, while only a handful of coronavirus infections have been officially reported; a three-year-old agreement with Russia broke down, and Riyadh flooded the world market with oil, sending the price plunging at levels not seen since the 1991 Gulf War.

Mohammed bin Salman deals with one catastrophe by moving on to the next

Each event is down to one man: Mohammed bin Salman. He deals with one catastrophe by moving on to the next. Decisions are taken with the speed of a rapid fire machine gun, without a second’s thought about the consequences.

Take the oil decision. The Financial Times calculated the decision would punch a $140bn hole in the revenue this year of the six Gulf states if the price of crude remained at $30 a barrel. The rich Gulf states Kuwait, UAE and Qatar can cope, but Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and Oman cannot. Saudi Arabia’s budget needs $83 a barrel to break even.

Maybe this was why one of the architects of the 2030 economic reform plan, Mohammed Tuwaijri, was removed from the Ministry of Economy and Planning last week and pushed upstairs as an advisor. This was the man who warned that if Saudi Arabia did not reform its finances, it would be broke in “three to four years”.

That was over three years ago.

The gambler

At best, pumping out oil at the rate it is doing should be classed as a gamble. But this is only one of a growing list. The next gamble is trashing Saudi Arabia’s carefully fabricated image as a leader of the Sunni Muslim world and the reliable custodian of the Muslim holy shrines.

This was a mighty source of Saudi soft power. It was also a source of legitimacy for the House of Saud.

The Bayaa, or Allegiance Council, was created in 2007 by King Abdullah to secure the future succession to the Saudi throne. Previously this had been the sole prerogative of the king.

Its main purpose was to avoid a power struggle and ensure a smooth succession after all of the sons of Abdulaziz, the founder and first king of Saudi Arabia, had died.

The council is intended to ensure the collective loyalty to the monarch of all of the branches of the Saudi royal family. It was originally composed of 34 members, representing the number of sons of Abdulaziz who themselves had male offspring. When a member died or resigned they were replaced by their son, or a place was allotted to their branch of the family in the future.

The council has two principal roles: to determine if the king is capable of fulfilling his functions or to accept the king’s resignation; and to announce who the new crown prince will be following the accession of a new king, chosen nominally from three candidates offered by the king.

While the choice of crown prince is determined by a vote, in reality the council is expected to execute the new king’s wishes.

However, a small but important clause in the council’s rules is that if the king is one of the founder’s grandsons, his crown prince cannot be from the same branch of the family (such as a brother or son).

This means that if Mohammed bin Salman becomes king, he would be expected to choose one of his cousins as crown prince.

When the then prime minister of Malaysia, Mahathir Mohamad, invited the leaders of Turkey, Qatar and Iran, all Saudi Arabia’s rivals, for a mini-summit of Islamic leaders in Kuala Lumpur last December, Mohammed bin Salman saw red.

Instead of embracing the summit, he turned his social media goons onto it, creating in the process a rival to the Organisation of Islamic Co-operation. He bullied Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan into not attending. Khan later apologised to Mahathir.

The result? The standing of Malaysia, Turkey, Qatar and even Pakistan have risen in the Sunni Islamic world and Saudi Arabia’s has diminished. But not as quickly as it is doing with its decision to close its borders to Umrah pilgrims, six weeks before the start of Ramadan.

The corona blackout

The spread of the coronavirus in the kingdom is not known, because doctors are not testing for the virus, and like Egypt, efforts are made to underplay its existence. Does anyone seriously believe that at a time when there are 9000 cases in Iran, 189 cases in Bahrain, 71 cases in Iraq, 74 cases in the UAE, 58 cases in Kuwait, there are only 21 cases in Saudi?

Nor is it known how long these closures will last. The resentment these arbitrary edicts are creating inside the kingdom and outside it is growing and will quickly become threatening to the crown prince. He is losing a lot of income but he is also gambling with his religious legitimacy as Saudi Arabia’s next king.

So the Saudis are stuck. They dare not admit the scale of the problem, but neither can they justify on medical grounds the decision to close the Eastern Province. There are, however, political motives to quarantine the Shia majority areas of Qatif and Al Ahsa.

Which leads me to Mohammed bin Salman’s latest decision to arrest his uncle Ahmed bin Abdulaziz.

The Trump cover

He knew, because Ahmed let this be known before he left his home in London, that his uncle got assurances from MI6 and the CIA that he would not be arrested on his return. By defying this injunction, the Saudi crown prince is relying on the cover given to him by US President Donald Trump and his son-in-law Jared Kushner.

Supposing however that neither of these two men are in office after November. What does Mohammed bin Salman think would happen to the voluminous CIA files on him? They would be passed to – say – a President Joe Biden, a declared Zionist with Israeli support, but who might be expected to have a very different view of bin Salman personally.

Anyone expecting Biden to change US foreign policy in the Middle East is in for a long wait, but that does not mean nothing would change.

Biden would have a personal interest in unravelling Trump’s private network of foreign allies. Mohammed bin Salman is one of them. The US, however, would remain a backer of the kingdom but not necessarily the new king, even if bin Salman presents the incoming president with a fait accompli.

At the very least, eliminating known CIA assets in the kingdom, like Mohammed bin Nayef, relies on the assumption that there will always be someone in the White House to suppress the instincts of the agency to fight back. In the current volatile political climate in the US, that is a huge gamble.

Would anyone – bar Trump – want a crown prince this unstable to become king in a country which, unlike Russia, China and Iran and Turkey, is a US military protectorate?

This is the biggest gamble Mohammed bin Salman has taken in his short career as crown prince. The real problem is that bin Salman, and his advisors, may be too stupid to realise the mistake he has just made.

By David Hearst

Source: Middle East Eye

The world is changing, monarchs were toppled in Europe and Russia, the same in the west when America had enough of King George…

The remaining Monarchs either begin ruling with more compassion or they will suffer the same fate as so many before them throughout history.

Only a fool makes an enemy of his own people, give a little get a little, give allot get allot.

He could still easily turn it all around by going outside on the streets amongst his people and helping them plus being there for them in many ways.

Many desire true leadership, not just management.