West Bank Annexation Plan Tests Gulf-Israeli Relations

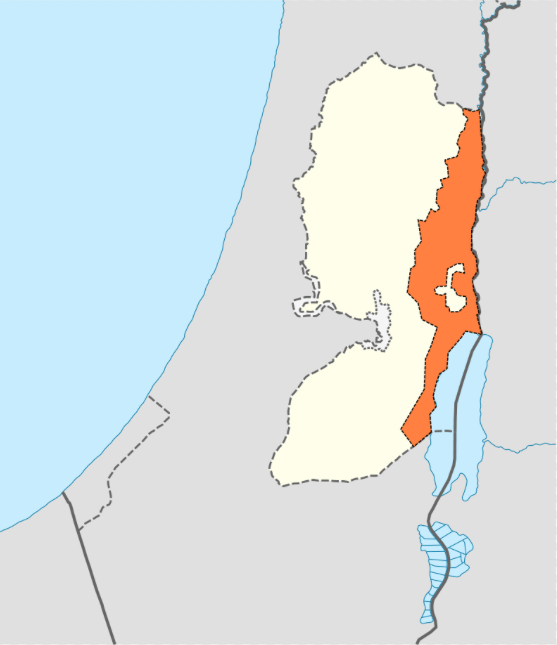

Despite warming relations with Israel, Gulf Arab monarchies are at least publicly opposing Tel Aviv’s unilateral decision to annex 30-40 percent of the West Bank next month. The main reason pertains to public opinion in Gulf states and the Islamic world at large remaining firmly pro-Palestinian.

Faced just nine years ago with a region-wide revolt that fueled unrest in Bahrain, and still an ongoing war in Yemen and low oil prices, Gulf leaders do not want their tacit partnerships with Israel to create new internal sources of anger that could harm their perceived legitimacy among citizens of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). Despite years of essentially abandoning the Palestinians and establishing barely covert ties with Israel, most Arab states in the Persian Gulf have little choice but to come out solidly against the pending annexations.

On June 1, the United Arab Emirates (UAE)’s minister of state for foreign affairs, Anwar Gargash, tweeted: “Continued Israeli talk of annexing Palestinian lands must stop.”

Nine days later, Abu Dhabi’s ambassador to Washington, Yousef al-Otaiba, wrote an op-ed for the Israeli newspaper Yedioth Ahronoth in which he made an appeal to Israelis not to proceed with annexation. He said his country could serve as an “open gateway connecting Israelis to the region and the world” but that the annexation of the West Bank could damage the process of improving ties between Tel Aviv and Arab states such as the UAE.

Otaiba also produced a video message in English, which accompanied his op-ed. “We wanted to speak directly to the Israelis. The message was all the progress that you’ve seen and the attitudes that have been changing toward Israel, people becoming more accepting of Israel and less hostile to Israel, all of that could be undermined by the decision to annex.”

At the beginning of June, the Emirati ambassador warned that the annexation would make the Middle East “even more unstable” and “will put an incredible amount of political pressure on our friends in Jordan.”

On June 10, Saudi Arabia’s Foreign Minister Prince Faisal bin Farhan addressed foreign ministers at a meeting of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) in which he said such an annexation would constitute a “dangerous escalation” and a “blatant challenge to international norms, laws, treaties, conventions and resolutions [which] does not take into consideration the rights of the Palestinian people.”

Bin Farhan emphasized that Riyadh opposes annexation and stands by its commitment to “peace as a strategic option.” The Arab-Israeli conflict must be resolved “in accordance with the relevant international resolutions, international law, and the Arab Peace Initiative of 2002,” he said.

At that same OIC meeting, Kuwaiti Foreign Minister Sheikh Ahmad Nasser Al-Mohammad Al-Sabah declared: “It is important for the international community to realize that such Israeli threats and provocations of annexation are a dangerous escalation that threatens all the efforts and the initiatives made to establish a comprehensive, just and lasting peace in the region.”

Adding to the PR offensive, four days earlier, Qatari Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs Sheikh Mohamed bin Abdelrahman Al-Thani spoke out against the Israeli move. The annexation “amounts to planting the last nail in the coffin of the peace process” while “bury[ing] any possibility of settling the conflict in the future”. He also warned that such “security, economic and social implications will be catastrophic for the entire region.”

But the Reality Is

These statements are a reminder that despite their keenness to cultivate closer ties with Israel, Gulf governments cannot be seen as entirely indifferent to the Palestinian struggle. If the Israelis proceed to annex parts of the West Bank next month, no one knows how the “Arab Street” will respond. All Arab regimes are concerned about public backlashes against leaders seen as indifferent or complicit in Israeli actions that would leave the Palestinians with a “Bantustan” in their homeland.

No Arab head of state has forgotten how or why Egyptian President Anwar Sadat’s life ended. Therefore, Israeli annexation of the Jordan Valley and Jewish settlements will likely change Gulf-Israeli relations on the surface, making them more confidential and less transparent.

But would it mean that the Gulf states, which have warmed to Israel in the past five years, would fundamentally change the substance of their tacit partnerships with the Jewish State? Probably not.

By virtue of Jordan’s border with the West Bank, a large Palestinian population, and Islamist parties vocally opposed to Amman staying in the Wadi Araba peace treaty, there is every reason to view Israeli annexation plans as threatening to the Hashemite Kingdom’s stability.

The Gulf states, however, are further away from the turmoil that this unilateral move on Tel Aviv’s part is expected to unleash. Moreover, Gulf governments see their economic, business, intelligence, and security relations with Israel as benefitting their interests, which will give the Emiratis and Saudis more incentive to not walk away from the ties that they have recently strengthened with Israel, even if they decide to do more to mask such still taboo relationships.

On June 16, the UAE’s Gargash went as far as to state that Abu Dhabi could still “work with Israel on some areas, including fighting the new coronavirus and on technology” despite having “political differences.” He emphasized that maintaining lines of communication with Israel is essential, suggesting that an annexation of parts of the West Bank will not prevent the Emiratis from continuing to cooperate with Israel in various domains.

Their Real Foes

In the grander geopolitical picture, leaders in Abu Dhabi and Riyadh see efforts to counter Turkish and Iranian agendas in the Middle East and North Africa as a much higher priority than standing up for the Palestinians.

Thus, the Emirates and Saudi kingdom find themselves in alignment with Israel, which shares their convictions about the need to counter Turkey, the Muslim Brotherhood, and the Islamic Republic of Iran. These dynamics, shared threat perceptions, and overlapping interests will not change at any point soon regardless of what Israel does to the West Bank next month.

Background to Growing Ties

Israel has never had formal diplomatic relations with any GCC state. Officially, each Arab monarchy in the Persian Gulf is Israel’s “enemy.” In reality, however, most GCC members —with the notable exception of Kuwait—which is firmly pro-Palestinian in its current foreign policy—have significantly warmed to Tel Aviv in the past five years. At the same time, most of their foreign policy agendas have de-prioritized support for the Palestinian struggle.

In April 2018, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MbS) was in New York City speaking in a closed-door meeting that reportedly included leaders of various Jewish organizations. According to Axios, MbS said: “It is about time the Palestinians take the proposals and agree to come to the negotiations table or shut up and stop complaining.”

In October 2018, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu paid Oman’s late Sultan Qaboos an official visit in Muscat. Four months later, at the Warsaw Conference on Middle East Peace and Security, Netanyahu met with Saudi Arabia and Oman’s chief diplomats.

Israelis have taken part in athletic competitions in the UAE and Qatar too. AGT International (an Israeli company based in Switzerland) recently signed a $800 million deal with the Emiratis. Jerusalem’s chief rabbi took a trip to Bahrain, where officials have made efforts to make an outreach to the Jewish community in the U.S. in the interest of moving closer to Israel. The long list of other examples of GCC-Israel engagement goes on.

There are also growing relations between the GCC states and Israel in the domains of intelligence and security. These ties are not new. They date back to the 1960s and 1970s. Yet, in recent years, Tel Aviv and Gulf states have been more public about such links amid a period in which most GCC members’ relations with Israel have been moving in the direction of normalization.

By Giorgio Cafiero and Claire Fuchs

Source: Consortium News