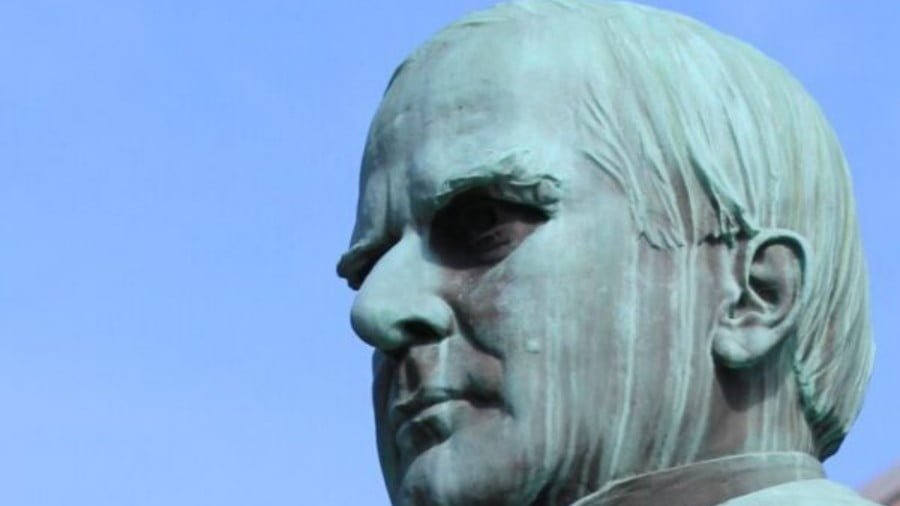

The Anarchist Assassination of U.S. President William McKinley and Its Links to the Murder of Tsar Alexander II

In 1901, there was a political coup d’etat in the United States that transformed the world and nobody noticed.

A beloved and twice-elected nationalist president was assassinated and replaced by a passionate supporter of the British Empire and America was on its disastrous path to empire in Asia and war in Europe.

The strategic context of the murder of William McKinley is seldom discussed. The extraordinary and deeply disturbing parallels between his murder and the sadistic slaughter 20 years before of Russia’s heroic Tsar Alexander II, friend of Abraham Lincoln and liberator of 24 million slaves has, to my knowledge, never before been explored or even suggested by anyone. Yet the same dark mastermind and imperial interests can be clearly identified behind both assassinations.

McKinley ended a 20-year-long economic depression that started in 1873, the longest in American history. He was pulled reluctantly into war with Spain and into annexing the Philippines but was strongly opposed to any further moves towards empire.

On September 6, 1901 McKinley was shot and mortally injured while visiting the World’s Fair in Buffalo in New York State. He died eight days later. His assassin was a Polish-American former steel worker called Leon Czolgosz who had been taken up by leading figures in the Anarcho-Syndicalist movement led with great prominence and charisma by former Russian Prince Peter Kropotkin from his secure, protected haven in Britain.

It was just over 20 years since Tsar Alexander II, the liberators of the serfs and joint architect with Otto von Bismarck of the Russian-German alliance that ended the 30 years of unparalleled invasions and destructions of great nations around the world by Britain and France, was assassinated on March 13, 1881 by Ignacy Hryniewiecki, also known as Ignaty Grinevitsky, another Polish anarchist recruited by the tiny secret anarchist cell of that grandly called itself the Narodnaya Volya, the People’s Will.

Czolgosz, one of life’s losers had come only recently to revolutionary anarchism, which advocated the murder of national leaders as “the propaganda of the deed,” only three years before in 1898. He had been taken up by the deeply rooted anarchist cell in Buffalo. Czolgosz was personally counseled and taught in the movements ideals and methods by Emma Goldman, who remains a beloved romantic figure of the American Left to this day,

Goldman (1869-1940) was a Lithuanian Jewish anarchist who came to the United States and is revered by the American Left and feminists as Red Emma for championing free speech, labor protests, women’s rights and birth control. In reality, she played no discernible role in achieving any of them. She also openly advocated bomb throwing by anarchists and unsuccessfully attempted to murder industrialist Henry Clay Frick, the right hand man of Andrew Carnegie in his Pittsburgh steelmaking empire.

Czolgosz met Goldman for the first time during one of her lectures in Cleveland, Ohio in May 1901. By then, Goldman had already met Kropotkin often including during his most recent American tour the previous month. Czolgosz openly admitted that Goldman had been his inspiration in the anarchist movement and after listening to her, he was ready to do anything he could to advance the cause.

After Goldman gave her lecture in Cleveland, Czolgosz approached the speakers’ platform and asked for reading recommendations. On the afternoon of July 12, 1901, he visited her at the home of Abraham Isaak, publisher of the newspaper Free Society in Chicago and introduced himself as Fred Nieman, (which means “nobody” a clear sign he was already thinking in conspiratorial terms.) Goldman later admitted to introducing him to her anarchist friends who were at the train station.

After the assassination, Goldman refused to condemn Czolgosz. Highly suspicious police and federal officials questioned Goldman, already a national figure. She complained they had given her “the third degree” and later writers have uncritically taken her at her word. But this was certainly just her lifelong pattern of wild, melodramatic exaggerations and outright lies.

She praised Czolgosz as a “supersensitive being,” an unlikely poetic description from someone who claimed to have only casually met him for a few minutes. It was language more likely to have been used by a lover inspiring a man to some “heroic, great deed” and it is quite likely they had had intimate relations.

Far from igniting a passionate mass anarchist movement across America, the murder of President McKinley did the opposite and discredited anarchism forever in the United States after 25 years of popularity tirelessly fanned by Kropotkin. Socialism, which angrily rejected the anarchists’ love of violence and assassination, superseded it and Eugene Debs won a million votes when he ran as head of the Socialist Party for president in 1912 against Woodrow Wilson, and Theodore Roosevelt.

Goldman was deported from the United States in 1919 after serving several short jail terms for minor offenses. She visited Russia but disapproved of the Soviet Union (she disapproved of everything she did not run or imagine) and eventually died in Canada in 1940.

Thirty years after her death, Goldman enjoyed a bizarre revival among American feminists which continues to this day. Adulation continues to pour down on her.

L. Doctorow’s pretentious, reverently praised and execrably bad 1975 novel “Ragtime” makes her the central, prophetic inspiring figure of the Ragtime era, a fantasy more unreal than Tolkien. The novel later became an embarrassingly awful though also acclaimed Broadway musical.

In real life, Goldman was an intimate friend and colleague for at least 30 years of the man who called himself Mephistopheles, after Goethe’s poetic version of Satan, Russian Prince Peter Kropotkin, who led the international anarchist movement for more than 40 years following the death of Mikhail Bakunin in 1876.

Goldman worshipped Kropotkin. She wrote of him: “We saw in him the father of modern anarchism, its revolutionary spokesman and brilliant exponent of its relation to science, philosophy, and progressive thought.”

So close were Kropotkin and Goldman that she visited him in Moscow in 1920 a year before his death and later attended his funeral. She always referred to him as “Peter.” It is likely they had been lovers. Her role in the McKinley assassination exactly parallels that of Sophia Perovskaya, the infamous, hate-crazed director of Hryniewiecki’s grenade murder attack on Tsar Alexander.

The most striking parallel with the murder of the Liberator Tsar was Kropotkin’s remarkable proximity to both crimes. As I have previously noted in these columns, Kropotkin is documented as having known Perovskaya in the notorious Nikolai Tchaikovsky Circle of Russian anarchists as early as 1872, nine years before the assassination. And he was later close to Goldman for the rest of the his long life (He lived to the age of 79.)

Czolgosz was apparently recruited in Cleveland by the anarchists and Goldman was his inspiration to do whatever he could for the movement.

Buffalo is not a large city and is relatively remote. It is 637 kilometers (about 400 miles) by road from New York City. Yet Kropotkin took the time to visit it and its anarchist cells for leisurely trips twice in close succession in 1897 and 1901. He spoke English fluently. His visit in late April 1901 at the end of a popular and very high-profile U.S. tour was only five months before the shooting of President McKinley in September. He had established warm personal ties with Buffalo’s anarchist leader Johann Most on his previous visit there three years before as documented in the study “Kropotkin in America” by Paul Avrich.

Avrich notes, “Kropotkin exerted an increasing influence on American anarchists, not to speak of socialists, Single Taxers and other reformers. During the 1880’s and 1890’s, his articles appeared in all the leading anarchist journals.”

It was much easier for violent anarchist cells in America to operate in small towns or obscure industrial cities where the police were far smaller, less well equipped, far less sophisticated and not attuned to the threat of revolutionary violence than in major metropolises like New York City, Los Angeles or Chicago.

All this Kropotkin knew well. In Buffalo, since his 1897 visit, his key contact was Most, a German expatriate who even in those circles was regarded as a wild and violent “firebrand,” according to Avrich. The World’s Fair had already been arranged to be held in Buffalo – a surprisingly remote and small location for such an event – and President McKinley was certain to visit it.

In other words, when poor, doomed President McKinley took his fatal train to obscure little Buffalo he was going to a stronghold of the most violent anarchist leader on the North American continent who had recently been in close personal contact with the movement’s international leader.

Kropotkin did not operate secretly or fearfully in the United States. He had enormous protection and influence. He was an honored guest in 1897 at meetings of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and gave a speech to the National Geographical Society in Washington, DC.

In 1901, Kropotkin stayed at the prestigious and luxurious Colonial Club in Cambridge Massachusetts. He was invited to the United States by the Lowell Institute. He also gave a guest lecture at Harvard. Goldman organized his busy and successful speaking schedule on the East Coast.

Like Tsar Alexander, McKinley was no evil tyrant but a successful reformer who had decisively improved terrible living conditions for scores of millions of people. He restored the U.S. economy by reviving the “national system ” of previous presidents such as Abraham Lincoln and James Garfield (both also assassinated). He especially increased industrial tariffs to keep British and German industries from undermining the U.S. industrial base with floods of subsidized and artificially supported “dumped” exports.

McKinley also settled a miners’ strike giving the oppressed workers decent rights and significant improvements in pay and conditions, the first such successful development in U.S. history. He was at the same time a trusted partner to Wall Street in maintaining business confidence and favorable investment conditions.

All this changed when McKinley’s vice president, the youngest in U.S. history, Theodore Roosevelt, succeeded to the presidency when McKinley succumbed to his wounds on September 14, 1901 after eight days of agony.

Roosevelt was named to the vice presidency supposedly to remove him from a position of real power as governor of New York State as the Wall Street moguls did not like or trust him. He filled the slot vacated by previous Vice President Garret Hobart, the highly capable former governor of Ohio, who died at the age of only 55 in 1899 after developing heart problems over that summer. Hobart’s death has been suggested but never seriously investigated as a possible poisoning. Had he lived, Roosevelt could never have been seriously considered as McKinley’s running mate in 1900.

Roosevelt devoted his next eight years in the presidency and the rest of his life to integrating the United States and the British Empire into a seamless web of racial imperialist oppression that dominated Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa and Asia and that destroyed the cultural history and heritage of the Native North American nations. But that is another story.

All this change was made possible by Czolgosz’s convenient two shots into President McKinley’s abdomen: Goldman lived in comfort and acclaim in different countries, always protected by the British Empire until her death in Canada in 1940 at the age of 71.