Operation Barkhane Will Embrace the Lead from Behind Stratagem

French President Macron’s recent announcement that he’ll be ending his country’s Operation Barkhane in West Africa’s Sahel region came with the caveat that France isn’t fully withdrawing from its anti-terrorist mission there, but is simply transforming the nature of its military presence in a manner that will be clarified later this month but will likely incorporate the “Lead From Behind” stratagem of delegating relevant responsibilities to partnered states with which it shares the same security interests.

The impending conclusion of France’s years-long Operation Barkhane in West Africa’s Sahel region might sound like a big deal to unaware observers but probably won’t change much at the end of the day. President Macron recently announced that his country’s anti-terrorist mission there will soon take on a new form, but he told everyone to wait until the end of the month for further details. Considering his support for multilateralism and prior reports about Paris’ interest in expanding the EU’s Takuba Task Force in the region, it can be expected that this new mission will incorporate the “Lead From Behind” stratagem. First practiced by the US during NATO’s 2011 War on Libya, this saw America delegating relevant responsibilities to partnered states like France and the UK with which it shared the same interests in overthrowing Gaddafi. In France’s case, it’ll likely position itself as the “first among equals” in a new coalition comprised of EU and West African countries that share the same interests in kinetically countering unconventional regional threats like terrorism and mass migration.

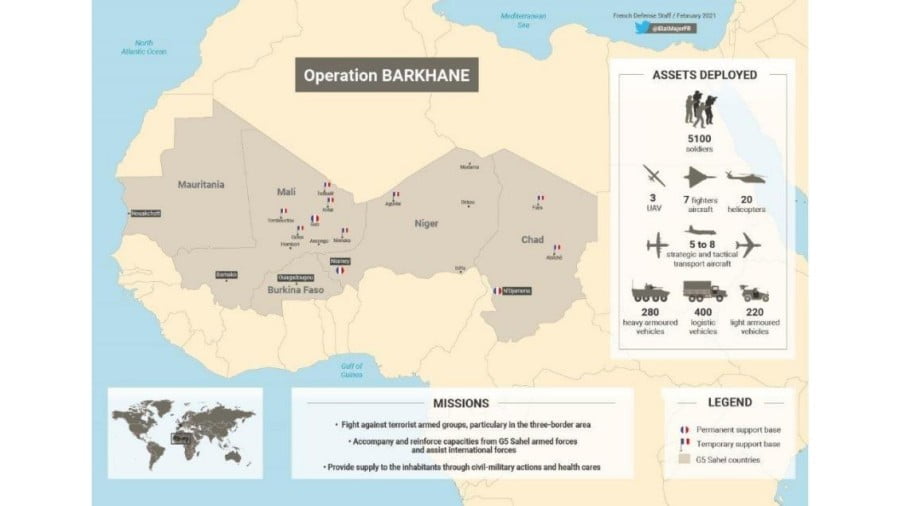

France had earlier been reluctant to share its decades-long hegemony in its post-colonial space that’s popularly referred as Françafrique, but begrudgingly accommodated American interests there during Washington’s so-called “Global War On Terror” (GWOT). The Western European Great Power launched its own regional variation thereof in 2013 at the behest of the Malian government and with the UNSC’s approval in order to help its West African partner defeat religious extremists that hijacked the Tuareg separatist movement which exploded the year prior following a military coup. Paris then expanded the area of its operations to include Mauritania, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Chad, all of which now coordinate with one another through what’s referred to as the G5 Sahel framework. Nevertheless, this new alliance failed to thwart regional terrorist threats, which have only increased in the years since. There have also been growing accusations that France is complicit in human rights abuses there and more interested in protecting its privileged economic interests than tackling terrorism.

Operation Barkhane therefore proved to be increasingly unpopular both in its region of operations and within France itself, which compelled Macron to consider superficially changing its nature with a faux conclusion to that campaign in order to appease public opinion. Two recent events served as the “plausible pretext” for him to finally make this move: the unexpected killing of long-serving Chadian leader Idriss Deby on the front lines of his country’s latest war with rebels and the so-called “coup within a coup” that occurred in Mali last month. The Chadian capital of N’Djamena hosts Operation Barkhane’s headquarters while Mali is the center of the G5 Sahel’s joint efforts. Although France backs the new Chadian authorities, it might discretely be concerned about further instability there. As for Mali, the so-called “anti-democratic” actions in that country served to justify France’s reduction of support to its military mission on the public basis of not “legitimizing” those contentious political developments.

There’s another for this change as well, and it’s that France knows that it can no longer retain full control over such a geographically broad and politically unstable space on its own, hence the need to resort to the “Lead From Behind” stratagem. Not only will the latter enable it to shift the burden of regional leadership, but also the blame for the lack of tangible military-political success all these years. France knows that it’s in the EU and West Africa’s shared interests to assist its mission there since none of those three parties want to see more terrorism or mass migration. It was perfect timing for him to make the announcement that he did in the run-up to the NATO Summit, which enabled him to set part of its agenda in a way which best serves his country’s interests. It’s unlikely that France will ever fully withdraw from the Sahel since doing so would voluntarily sacrifice its hegemony there as well as exacerbate the two security threats that its military intervention sought to contain in the first place, so nobody should ever expect anything as dramatic as that.

The European and West African elite, each of which benefits from France’s indefinite military operations there, understand Paris’ concerns and are therefore expected to participate in its implied “Lead From Behind” stratagem. After all, the optics also serve their interests too, to say nothing of the substance. The EU wants to show that multilateralism has been revived after the four tumultuous years of unilateralism under former US President Trump while West African governments want to show their people that they’re trying to take more control over managing regional events on their own as much as possible. Closer EU-West African security coordination in the Sahel under France’s leadership can also lead to the expansion of relations in other spheres as well, especially the political and economic ones. Paris will have to “accommodate” more semi-independent behavior from a growing list of actors in Françafrique, but it believes that this is an inevitable evolution of its strategy which will enable it to indefinitely retain its hegemony there in the emerging Multipolar World Order.