Bamboo Diplomacy: The China-SE Asia Romance

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations is monopolizing the Asian and Global South spotlight for no fewer than 10 days, this week and the next, across a flurry of regional and international summits.

First stop is Phnom Penh for the 25th China-ASEAN summit, the 25th ASEAN Plus Three (APT) summit, and the 17th East Asia Summit, all the way to Sunday.

Next week will be Bali for the Group of Twenty, followed by Bangkok for the APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) summit.

No wonder the diplomatic spin across Southeast Asia is all about global governance entering the “Asia moment” – as coined by Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi. It’s a moment that may be set to last a century – and beyond.

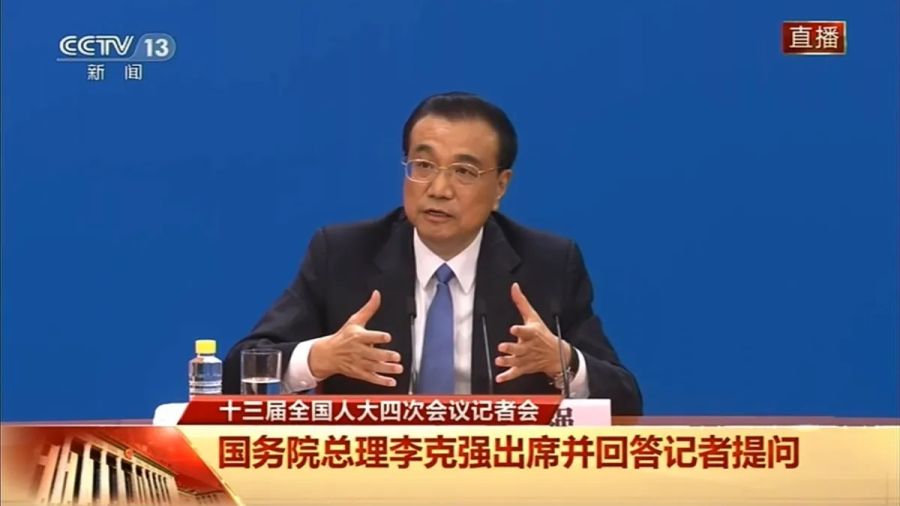

In parallel, Chinese diplomacy is also predictably on a roll. Premier Li Keqiang – who will step down next March, after two terms in office – heads Beijing’s delegation in Cambodia after two key Southeast Asian interactions: the visit by Vietnamese leader Nguyen Phu Trong to China and Chinese Vice-Premier Han Zheng’s visit to Singapore.

All that fits the pattern of increasing China-Southeast Asia integration. Since 2020, ASEAN has been China’s largest trading partner. China has been ASEAN’s top trading partner since 2009. Total China-ASEAN trade reached $878 billion in 2021, up from $686 billion in 2020. It had been $9 billion in 1991. China-ASEAN investment was more than US$340 billion by last July, according to the Ministry of Commerce in Beijing.

Interests particularly converge on deepening RCEP – the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, the largest trade deal on the planet. That translates in practice as closer integration of supply chains, infrastructure connectivity and the building of a new international land-sea trade corridor.

So it’s no wonder all the slogans for these 10 days of summits reflect closer integration. The ASEAN 2022 theme is “ASEAN A C T: Addressing Challenges Together.” The Indonesians defined the G20 as “Recover Together, Recover Stronger.” And the Thais defined APEC as “Open. Connect. Balance.”

Now bend that bamboo

Timing is everything. After the Communist Party Congress defined the parameters of “peaceful modernization” and how Beijing will develop globalization 2.0 with Chinese characteristics, diplomacy was ready to go on the offensive. And not only across Southeast Asia.

On South Asia, Beijing hosted Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif. Regardless of who holds power in Islamabad, Pakistan remains strategically crucial, with the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) connecting to the Western Indian Ocean, the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea and beyond toward Europe.

Pakistan cannot be left to implode under severe financial constraints. So it’s no wonder that Xi Jinping promised that “China will continue to do its best to support Pakistan in stabilizing its financial situation.”

They were very specific on CPEC: Priorities are the construction of auxiliary infrastructure for Gwadar port in the Arabian Sea and to upgrade the Karachi Circular Railway project.

On Africa, Beijing hosted Tanzanian President Samia Suluhu.

Beijing is constantly inviting African leaders to discuss trade and investment in a “South-South” format. So it’s no wonder the Chinese find receptivity to their ideas and necessities to an extent that’s absolutely out of the question in the West.

China-Tanzania is now a “comprehensive strategic cooperative partnership.” This is quite significant, because now Tanzania is on the same level as Vietnam and Cambodia, as well as Kenya, Zimbabwe and Mozambique, in China’s ultra-complex “friendship” hierarchy. Tanzania, incidentally, is a crucial source of soybeans.

On Europe, Beijing received German Chancellor Olof Scholz for a lightning-fast visit, leading a caravan of business executives. Beijing may not “save” Berlin from its current self-enforced predicament; at least it’s clear that German business will not go for “decoupling” from China.

It’s crucial to remember that Vietnam, Pakistan and Tanzania are all key partners in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). And the same applies to Germany: The Ruhr Valley is the privileged Belt and Road terminal in the European Union.

All that leaves the Quad, AUKUS, the “Indo-Pacific Framework” and the “Partners for a Blue Pacific” – different denominations of isolation/demonization of China – trailing in the dust. Not to mention the imperial drive to impose “decoupling.”

Beijing knows full well Singapore’s role as the essential Southeast Asian finance/tech node. Hence the signing of 19 bilateral deals, some related to high tech.

But as far as optics go, the key visitor may have been Vietnam. Forget about their South China Sea tensions. For Beijing, what matters is that Nguyen Phu Trong came to visit immediately after the Communist Party conference – somehow echoing the centuries-old tribute system. Hanoi may have no interest whatsoever in being strategically dominated by Beijing. But demonstrating respect – and neutrality – is the Asian diplomatic way to go.

Trong made a point to note that “Vietnam considers its friendly cooperation with China the first priority of its foreign policy.”

That may not necessarily mean that Hanoi is privileging Beijing over Washington. The meaning of “first priority” seems to be clear: China and Vietnam agreed to turbocharge work on the Code of Conduct for the South China Sea. That also happens to be a key Chinese priority – as it keeps the process as an inter-Asian matter without the predictable “foreign interference.”

It was Trong himself who first came up with the fascinating idea of “bamboo diplomacy“: soft, clever, persistent and resolute. The concept may be easily applied to the whole of China-Southeast Asian relations.

Round up the jargon

This week in Phnom Penh, there are serious discussions on deepening the RCEP; problems on the food and energy front; and speeding up the negotiation of what is billed as the 3.0 version of the China-ASEAN Free Trade Area.

All that involves a key issue: the interconnection of BRI projects and ASEAN’s so-called Outlook on the Indo-Pacific – a series of ASEAN development strategies.

A good example is the endless high-speed-rail saga related to connecting Yunnan province in southern China to Singapore.

The building of the Thai section was proposed even ahead of the Laos section. Yet Kunming-Vientiane was ready in record time – and is rolling – while the Thais have been endlessly haggling and lost in corruption and internal infighting: Only part of their section at best will be finished by 2028.

The same applies to Malaysia and Singapore still not finding an agreement. This is the case of a key connectivity corridor across Southeast Asia hobbled by internal and bilateral trouble. In parallel, the construction of the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway has proceeded with only a few bumps.

As much as China and ASEAN established an official comprehensive strategic partnership in 2021, several key BRI projects are intimately connected to Southeast Asia. After all, Xi Jinping launched the Maritime Silk Road concept in Jakarta more than nine years ago.

The same applies to solving the seemingly intractable issues of the South China Sea. The Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea was signed by Beijing and ASEAN 20 years ago.

In geopolitical terms, the 10-headed ASEAN hydra is a unique beast: a living lab of peaceful – civilizational – co-existence.

Trade has always been the secret weapon. It has always been a two-way road between China and Southeast Asia. History tells us that the willingness of Southeast Asian rulers to submit – even if symbolically – to China explains the predominant Make Trade Not War ethos.

The main exception was Vietnam, occupied by China from 111 BC until AD 963-979. But even as Vietnam became independent from China a millennium ago, it always remained deeply influenced by Chinese culture. In contrast, the Chinese who were assimilated into Thai culture gave up Confucianism and ended up adopting Indian court rituals.

In parallel, as Professor Wang Gungwu in Singapore always noted, paying tribute and requesting protection from the Chinese imperial dynasties never meant that Beijing could do what it wanted across Southeast Asia.

In the current incandescent geopolitical juncture, China is definitely not interested in playing divide and rule in Southeast Asia. Chinese strategic planners seem to understand that ASEAN carries a lot of soft power smoothing the big power play across Southeast Asia, offering a platform for all to engage with each other.

No one seems to mistrust ASEAN. That also explains why the Southeast Asians have come up with an acronym fest that basically hails cooperation – from ASEM and ASEAN+3 to APEC.

So it’s enlightening to remember that “China is prepared to open itself to ASEAN countries,” as Xi himself said when he launched the Maritime Silk Road in Jakarta in 2013. “China is committed to greater connectivity with ASEAN countries” – and “China will propose the establishment of an Asian infrastructure investment bank that would give priority to ASEAN countries’ needs.”

The bilateral relationships between China and each of the 10 members of ASEAN may carry their own particular complications. But there seems to be a consensus that no bilateral will determine the future of China-Southeast Asian relations.

The discussions this week in Phnom Penh and next week in Bali and Bangkok suggest that Southeast Asia has ruled out either extreme: paying tribute or demonizing China.

Across Southeast Asia the Chinese diaspora has been informally referred to for decades as “the bamboo internet.” The same metaphor would apply to China-Southeast Asia diplomacy: Gotta go the bamboo way. Soft, clever, persistent – and enduring.