On Reforming the Agricultural Industry of India

Future researchers on the political processes occurring in modern-day India will designate September 27, 2020 as an extremely significant date. On this day the parliament, followed by the country’s president, passed and ratified three laws that launch a process involving radical reform in agriculture, which employs more than half of India’s working-age population but produces only 15% of the national GDP.

Actually, these two figures explain both how pressing the actual range of problems is concerning reforming the country’s agricultural sector and the inevitable painfulness of the transition process. And this despite the fact that the agricultural industry since India has become independent has demonstrated definite success, and for the first time in centuries of its history has barred the prospect of mass famine (even given adverse weather conditions) in a country with a total population of 1.3 billion people.

But the leadership of India, which lays claim to being one of the world’s leading players, sees the current situation in agriculture as one that cannot be tolerated any more. Therefore, Prime Minister Narendra Modi is undoubtedly right when he pointed to the date of September 27, 2020 as the “watershed moment” between the country’s past and its future. He is bursting with optimism (nothing else could be the case) in his assessments for the prospects of reforming agriculture, and he himself initiated laying the groundwork for the regulatory framework back in 2017.

But it is unlikely that he (or anyone else for that matter) today knows what will actually happen, because launching this process is akin to how a minesweeper moves across a minefield, with no opportunity for even a single error.

It is worth pointing out merely one example of reforming this kind of agrarian country, which was Russia 150 years ago, from the 1860s until the 1930s. This period witnessed several major social cataclysms caused by the course taken by the Russian “transition process”. Its direct offspring, the “bloodsucking wealthy peasant”, was an enemy not only for Vladimir Lenin, but for someone else located at the opposite end of the political ideological spectrum: Fyodor Dostoyevskiy. During the period of collectivization, it was necessary to correct (using methods that are common knowledge to everyone) the “imbalances” that arose during the period when the “invisible hand of the market” (“whose work should not be interrupted”) operates.

Both conscientious critics of the Indian agricultural reform process initiated by Narendra Modi and his political opponents (as well as ordinary opponents) of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, while agreeing that the need to liberalize the agricultural sector actually exists, point to the potential “side effects” (like those that once occurred in Russia) in the form of ruin for individual small- and medium-sized farmers, as well as further enrichment for large farm corporations and the resellers of manufactured goods.

In response, accusations are resounding both that people have not carefully examined the laws (in which “everything is provided for”), or simply engaging in speculation, or blindly following the Communists, Maoists, Naxalites, and other bad people who just need any reason to discredit the BJP and the current government. It is worth noting right away that if even the prime minister is not squeamish about these “lines of reasoning”, then apparently even now in the country (and around it, which the author will touch upon below) a situation is developing marked by increased tension.

The reproach leveled by critics about the procedural aspects for laying the groundwork for, and then passing, these laws seems very serious. Some affirm that opposition parties and interested stakeholder nongovernmental organizations did not participate in preliminary discussion about them. If the claims put forth by the leading opposition party Indian National Congress are fair ones – that debate on a more or less ongoing basis was not done even in specialized parliamentary committees – then another statement made by the INC is also true: in this case, the government adhered to its well-known “shock-and-awe strategy”.

This would be a good strategy if the goal were to “push” laws through the parliament quickly – and in the format desired by their initiators. But just like any strategy, this one has its drawbacks, the most pressing of which (so far) has turned out to be the manifestation of dissatisfaction on the streets by those who felt that their interests were ignored. After September 27, mass demonstrations by some farm workers rose to a new qualitative and quantitative level, and received support from other professional associations around the country – and even from some foreign politicians.

The capital actually found itself in a state of siege when, to prevent hundreds of thousands of protesters from entering Delhi, the police not only used “traditional” tear gas and water cannons, but also dug across access roads, erected barricades on them, and erected trucks across the roads.

As of December 8, the demands put forth by protesters included several items. Among these, the main ones boil down to rescinding (by holding an extraordinary session of the parliament) three new laws in the field of agriculture, and to re-enact the previous rule governing the state procurement of farm products at a certain minimum price that is guaranteed: the minimum support price.

Accepting these and other requirements would mean that Narendra Modi’s government rejects the course towards liberalizing the agricultural sector and decreasing the role that the state plays in it.

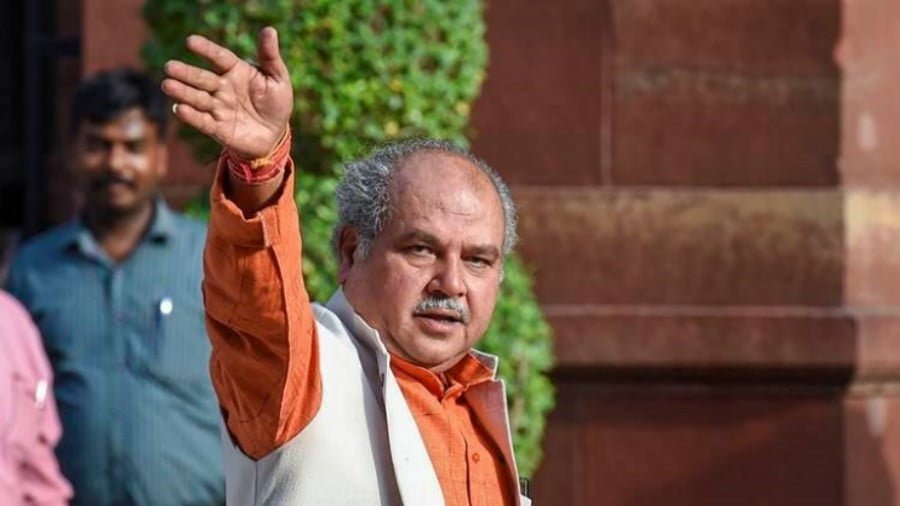

On December 16, in an interview with The Indian Express, Indian Minister of Agriculture Narendra Singh Tomar stated that the government is first waiting for a response to the list of “concessions” proposed during several rounds of negotiations with those representing the protesting farmers. Second, he insisted that the government has a mandate to implement these reforms. In his opinion, the results of the latest general elections held in the spring of 2019 constitute evidence of this: during these, the BJP won 303 out of a total of 543 seats in the lower house of the Indian Parliament.

As noted above, everything that has been transpiring in India in recent months has already sparked responses from politicians in those countries that are traditionally concerned with “human rights” issues wherever they arise. Moreover, the assessments put forth are frequently abundantly clear, and harsh as well. In particular, the statements on this topic made by the Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau brought relations to the brink of discontinuance.

Incidentally, it is curious to see how the new US Vice President Kamala Harris, who is half-Indian, will behave in this matter, whose election to this position caused plenty of euphoria in India. So far, it is doubtful that before January 20, when she officially takes over her position, everything in India will “dissipate” (in some way, and on its own). That means that the very need to publicly define any position on the “internationally high-profile” events in her mother’s homeland will disappear. Along with that, a screenshot that appeared on December 1 in social media networks – one that was allegedly of her Twitter post in support of protesting Indian farmers – was soon declared “fake news”.

Meanwhile, several members of the US Congress from both parties have already expressed their unfavorable assessments of both “anti-farming” laws and the actions taken by the Indian police towards the protesters.

From the standpoint of this article’s author, the presence of a significant foreign policy component in a (seemingly) purely domestic Indian problem is not due at all to the “human rights” aspects of evaluating the actions taken by the police vis-a-vis the protesters, but to a much more serious factor involving the country’s arrival in the restricted club of leading world players. In regard to that, how conditional the separation is between the domestic and foreign aspects of how the state operates is particularly sharply visible.

That is why such close attention is being devoted, for example, to the current domestic political turbulence in the United States. Previously, NEO talked about the international aspects of the consequences passing a number of laws affecting interests held by various minorities in India, mainly Muslims.

But it seems that there has been no precedent over the last two or three decades for what is happening in India now in connection with the ongoing process of agricultural reforms. All that remains is to wish that the people and the country’s leadership pass through the trials that have befallen them without incurring heavy losses.