Other People’s Cultural Assets Are Up for Grabs

The rapacious conduct of the big hyenas is being replicated by their camp followers. Not to be outdone, Kosovo Albanians are laying claim to Serbian cultural monuments in Kosovo.

A controversy has recently erupted in Mexico, of the type that may quite often be seen in other similarly defrauded countries. Its focus is the magnificent quetzal-plumed headdress of the last Aztec emperor Moctezuma which, contrary to the misleading impression encouraged by the Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, is not displayed there at all. It is actually located, of all places, in the Ethnological Museum in Vienna, Austria.

The impression is misleading because as recalled by all visitors to the Mexican Museo de Antropologia the headdress occupies a deservedly prominent position among the museum’s numerous artefacts. Viewers are not informed, however, that what is on display there is not the genuine item but a skilfully manufactured replica. Nor are they told where the genuine article is located, or what unusual circumstances explain its transfer to a minor European country that has no visible connection to the safekeeping of Mexican people’s national heritage. Unless, of course, we take into account the brief reign of Maximillian von Habsburg as the foreign-imposed emperor of Mexico in the nineteenth century. But as it turns out, that seemingly plausible assumption is a false trail. The defeated Aztec emperor’s headdress was purloined and removed to Europe by the victorious Spanish conquistadors half a millennium ago, and it ended up in Hapsburg Vienna through labyrinthine dynastic channels. But that is a pedantic clarification of the artefact’s odyssey which in principle scarcely makes any difference.

Moctezuma’s headdress

The fate of this national treasure par excellence of the people of Mexico is vividly illustrative of the policy of cultural appropriation (or, perhaps, expropriation would be just as good a word) that has been and still is zealously practiced by shameless Western imperialists. Cultural vandalism would probably be the best terms of all.

The fabled Elgin Marbles immediately come to mind. The history of this section of the Parthenon that was brazenly looted by the Earl of Elgin, at the time the Ambassador Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary of His Britannic Majesty to the Sublime Porte of Selim III, Sultan of Turkey, of whose realm Greece then formed a part, is emblematic of Western looting of other nations’ cultural patrimony. Lord Elgin cast an eye on the Parthenon and saw an opportunity to acquire what he could of it by bribing the corruptible Ottoman bureaucracy. After making a sweetheart deal with the local pasha (camouflaged with a forged imperial firman the original copy of which was never found in the meticulously kept Turkish archives) he arranged for the artefacts to be shipped by sea to Britain, where they are now on display in the Duveen Gallery of the British Museum. The pattern of iniquitous deal making with third parties, while excluding the party with the direct and natural interest in the matter, henceforth became a feature of Western and in particular British policy. Greece’s attempts going back two centuries to reclaim its stolen treasure have been stonewalled and, obviously, have had no success.

One of the arguments advanced by Western opponents of restitution is that, were all similar claims to be honoured, Western museums would be emptied of the objects on display there. Their argument is breathtakingly cynical, but they also make a valid point. Yes, of course, the bust of Nefertiti in Berlin’s Neues Museum in this connection readily comes to mind, as well as thousands of other looted objects in museums throughout the continent. Goering’s robbery spree across occupied Europe was but a crude imitation of the way these artistic treasures were acquired in the first place. Though scathingly denounced for his depredations after the war, in Marxian terms in the milieu in which he operated the Reichsmarschall was not an aberration. He was merely expropriating the expropriators.

The point was brilliantly illustrated much later, at the time of the memorable liberation of Iraq by coalition armies. Specially trained units made a bee line to Iraq’s National Museum immediately upon the taking of Baghdad, and not because anyone thought that the elusive weapons of mass destruction were hidden among its treasures. The Museum was systematically pillaged, Goering-style, never mind the irksome 1954 Hague Convention on the protection of cultural property which sternly forbids it. Shortly thereafter, Iraqi artefacts began to emerge and were being offered in copious quantities to eager collectors all over Europe and North America.

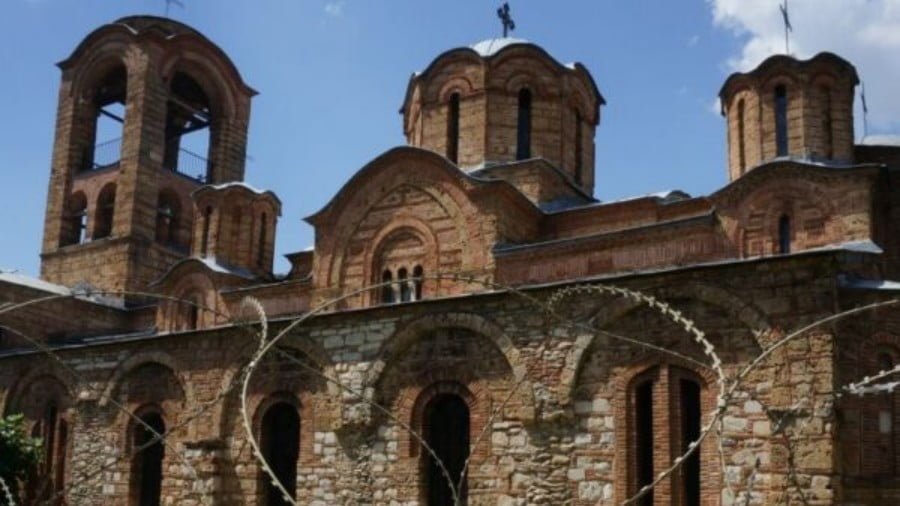

Predictably, the rapacious conduct of the big hyenas is being replicated by their camp followers. Not to be outdone, Kosovo Albanians are laying claim to Serbian cultural monuments in Kosovo and Metohija.

Serbian cultural monuments in Kosovo and Metohija

As seen in the map, Serbian cultural markers thickly cover the entirety of the tiny province’s territory, with none reflecting a culturally significant historical presence by another ethnicity. Undaunted by that, a pseudo-scholarly rationale for the cultural expropriation of Serbian monuments in Kosovo and their reclassification as Albanian is currently being developed in leading Western institutions of learning, on behalf of their Kosovo Albanian clients. The work of Sir Noel Malcolm, a King’s Scholar at Eton College, “Kosovo: A Short History”, is a case in point in that regard. It is a companion volume to his earlier hit piece of similar inspiration, “Bosnia: A Short History”.

Returning to Moctezuma’s headdress, or penacho as they call it in Mexico, Vienna Ethnological Museum director Christian Schicklbruber offered some revealing views in the matter. “The Museum,” he stated, “cannot make any decisions with respect to political issues.” As to who the penacho should belong to, he indicated that he preferred to call it “shared cultural patrimony,” stressing that “legally it belongs to Austria, but ethically and morally it is a shared cultural item. I would call it ‘ours,’ not mine, it is not Austrian, all of us share it.” Anyway, according to Herr Schicklgruber, it is a matter for the Austrian parliament and Ministry of Culture to decide.

Bank robbers should take note and be inspired by the Schicklgruber Doctrine (and we will not trivialize it by speculating what famous individual the museum director might be related to). They should try arguing in court that their heist is not really the property of the bank at all, but a shared financial asset to which they are entirely entitled to lay an equal and valid claim.