Disregarding History: Tigray and the Collapse of Evangelical Neoliberalism

June 2021 Elections

On June 21st Ethiopians headed to the polls. It was widely expected that the incumbent prime minister Abiy Ahmed would emerge the winner. 47 parties have participated in the general and regional elections. Abiy’s Prosperity Party leads the chart on the number of registered candidates contesting for seats at the parliament with a total of 2,432 aspirants. This is closely followed by a rival party, Ethiopian Citizens for Social Justice, which has fielded 1,385 candidates in the election. Around 37 million of Ethiopia’s 109 million people are registered to vote.

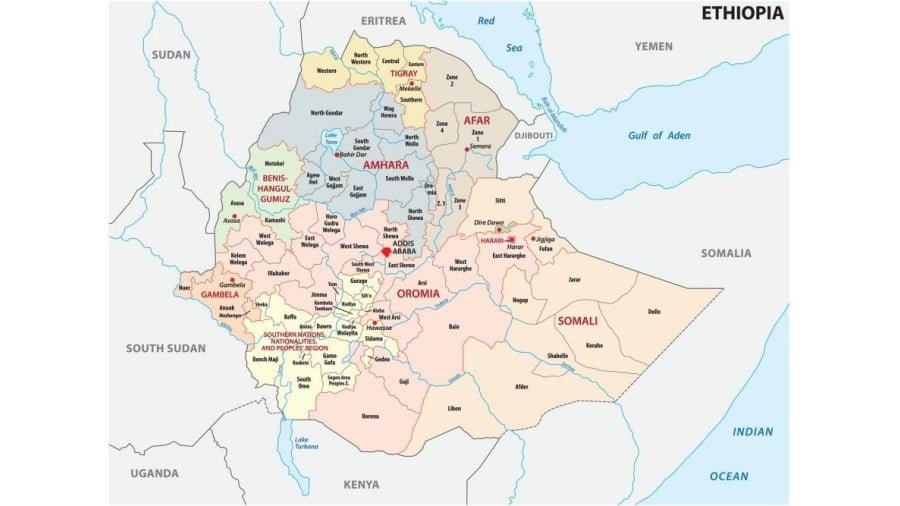

Abiy became prime minister in April 2018 following the resignation of his predecessor, Hailemariam Desalegn, who renounced his chairmanship of the then ruling coalition, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). The EPRDF coalition, which consisted of four political parties, dominated Ethiopia’s politics from 1991 to 2019. The strongest party of the coalition was the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), representing 6% of a national population of over 100 million, and had dominated federal politics for thirty years. Abiy was the first ethnic Oromo to lead his country. In 2019, Abiy directed the dissolution and merger of the EPRDF into the Prosperity Party, widely perceived as a move towards greater centralization of power.

Authorities could not hold polls on election day in four of Ethiopia’s 10 regions. Voters in one of those regions, Sidama, went to the polls a day late due to logistical problems. No date for a vote in Tigray had been determined. Not only are many senior members of the TPLF in custody but so also are many opposition figures in Oromo, the region surrounding Addis Ababa. Addis Ababa had been the political and religious center of the Oromo people before they were driven out by force. Some political parties have called for exclusion of Oromo people and their administration from the city and have been accused of provoking ethnic conflict between the Oromo and the Amhara people. The European Union has withdrawn its election observation mission to Ethiopia, in protest at the regime’s failure to meet “standard requirements” relating to security and the independence of the observer group.

Unfree and Unfair

Touted as the first multi-party election in sixteen years, the truth is that since becoming prime minister in 2018 Abiy had crippled the then ruling coalition and its dominant party, the TPLF, rebranding the coalition as his own new Prosperity Party, without the consent of the TPLF. “Free and fair” the election certainly is not since not only has Abiy crippled the TPLF at national level, but the TPLF’s major power base, the government of Tigray, has been dismantled in the coordinated pincer invasion of Tigray by the dictator of Eritrea in an unholy alliance with Abiy. In early 2020, the National Election Board of Ethiopia had already deregistered the TPLF as a political party, accusing the movement of violence. Months later the TPLF was designated a terror group. Earlier in November, Abiy imposed a state of emergency in Tigray for six months. This facilitated an Ethiopian army offensive, with internet and telephone services cut off.

The TPLF had protested Abiy’s cancellation of the originally scheduled election for August 2020 – on the pretext of Covid and without at that time naming an alternative date – by arranging its own election in Tigray and announcing its withdrawal from the Addis Ababa regime, a claim to secession which is formally allowed by the Soviet-inspired Ethiopian constitution. The Tigray election was held in September 2020, while Tigray’s government warned that any intervention by federal government would amount to a “declaration of war”. TPLF gained a majority in the contest of five parties. 85% of eligible voters cast their ballots. Predictably, Ethiopia’s upper house of parliament ruled in response that the polls for regional parliaments and other positions were unconstitutional. Some 2.7 million people in the Tigray region had cast their votes at more than 2,600 polling stations.

Changing Perceptions of Abiy

Western perception of Abiy has changed radically in the past three years, from enthusiastically positive to balefully negative. Abiy succeeded initially in creating the impression of ushering in a period of considerable social and political change towards greater democracy, regional peace, and prosperity. His siren song of neoliberalism was particularly welcome to western ears. But in-depth analysis seems either to have been missing or disregarded, doubtless much to the chagrin of the Nobel Foundation whose judgments sometimes appear recklessly optimistic (they awarded Abiy the peace prize in October 2019). Abiy’s naïve neoliberalism expropriated the real merit for decades of significant economic advances in Ethiopia under the Chinese model of State developmentalism from the previous EPRTF administration. His promises were followed not by economic growth but by a near 50% decline in foreign investment.

This has negatively impacted the national currency, while five million of the country’s population in the northern regions of Tigray, Amhara and Afar are threatened by famine. The most significant national measure towards future prosperity is the outcome of previous EPRTF policy – the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam which has been under construction since 2011 and will not be full until sometime in the period 2026-2036. This has the potential to provide electricity to roughly 100 million people, many of them peasant farmers.

Do Not Mess with Tigray

Presumably in the name of greater ethnic justice, Abiy has provoked a civil war that has no promise of quick solution. Appearing to have learned little from the history of his country, he has prioritized centralization of power over regional and ethnic security, spurning the advantages of previous polices of ethnic autonomy. He has overturned the established power base of the TLFP to little advantage, ignoring the centrality of Tigray to Ethiopian national identity. The TLFP resisted and eventually took down Haile Selassie in 1974. The TLFP later resisted the Stalinist excesses of the Marxist Derg administration that succeeded Selassie, and eventually took it down in 1991. The TLFP made a major contribution to the years of relative stability and economic progress under the succeeding era of the EPRDF coalition, even if Ethiopia continued to be one of the poorest countries of the world. And the TLFP may well take down Abiy.

Curious Alliance with Eritrea

Abiy has bolstered the cause of the mercurial dictator of Eritrea, whose foreign minister recently blamed the USA for backing the TPLF for the last 20 years. Whereas Ethiopia has been a partner of AFRICOM and a troop contributor to AMISOM – the UN Peacekeeping Mission in Somalia, which has been under US command – Eritrea’s dictator, Isaias Afwerki, has tried to minimize the influence of the USA, UK, and the EU on Eritrea, and to step aside from western debt traps. Eritrea has refused to participate in AFRICOM and does not allow western troops access to its Red Sea port of Massawa. While these measures might normally invite the cheers of anti-imperialists, Eritrea’s intentions in Tigray, with which it has previously been at war, many times, raise suspicions that the interests of the predominantly peasant Tigray people have been sold out for political and ethnic gain in Addis Ababa and in a manner that may eventually weaken Ethiopia as a whole.

Sanctimonious US Inefficacy

On May 23 Secretary of State Antony Blinken imposed wide-ranging restrictions on economic and security assistance to Ethiopia and Eritrea after parties to the conflict in Tigray had “taken no meaningful steps to end hostilities.” The Biden administration has repeatedly called for the immediate withdrawal of Eritrean and Amhara forces from the Tigray region and asked for the African Union to help resolve the crisis. Eritrea won its independence from Ethiopia in 1991 (with the assistance of Arab neighbors such as Iraq and Libya, and at the price of half a million lives), thus cutting Ethiopia – which, like Eritrea, is predominantly Christian – off from the sea.

With US and UK support, previous Ethiopian leader (to 1974) Emperor Haile Selassie had federated with Eritrea in 1952 only to annex it in 1962. This instigated the Eritrean War of Independence, which continued to 1991. Also involved in the recent Tigray invasion are forces of Amhara, a northern regional state and one of the two largest ethnolinguistic peoples of Ethiopia, constituting a quarter of the country’s total population. Following the November 2020 invasion of Tigray by Ethiopian National Defense Forces, Eritrean forces and the Amhara, several thousands have lost their lives and 2 million have been displaced.

Another Astonishingly Misjudged “Peace” Prize

Accepting a 2002 arbitration ruling which Ethiopia had ignored for sixteen years, Abiy Ahmed was awarded a Nobel peace prize in 2019 – prematurely, most may now agree – for signing an accord with Eritrea’s dictator Isaias Afwerki – who would soon energetically assist Abiy’s massacre of Afwerki’s foes, the TPLF, in the northernmost Ethiopian territory of Tigray. Abiy’s giddy projections delivered to the World Economic Forum in January 2019 pleased international investor nations like the USA, UK, Germany, France, Russia and, above all, China, hoping to seize a share of Ethiopia’s early 21st century growing prosperity. But many recoiled when the country found itself in the crosshairs of (a relatively mild form of) US sanctions warfare. To deflect international criticism of disastrous measures whose consequences surely could have been foreseen or mitigated, the Abiy government blamed the crisis on the TPLF, accusing it of an attack on an Ethiopian military base at Sero. But this may well have been a response to provocation, and it supplied Abiy with needed pretext. Preparations for war had been under way for some time. Abiy had previously dismantled the previous coalition whose leading party, the TPLF, afforded Tigreans a privileged place in federal affairs, and inserted his own, the Prosperity party. The TPLF had been invited to join, but declined, which of course they were well within their rights so to do.

Disproportionate Reprisal

Tigray’s principal fault was that it proceeded with an election that it had been promised, and in response Abiy proceeded to dismantle Tigray’s entire government structure, interfere with the region’s physical infrastructure, invade militarily and commit human rights violations:

The people of Tigray have been denied access to food, health services, electricity, internet, telecom, banking, and independent media. Their means of livelihood have been deliberately destroyed: crops have been burned down, cattle killed and looted, and grain stores have been destroyed.

All this in a country whose constitution allows secession. Abiy, a Pentecostal Christian and former intelligence officer, had previously initiated a campaign against Tigrean opinion leaders and another against the government of Tigray. He crippled the region’s economy with blockades. He accused the TPLF of instigating ethnic conflict, but many ethnic groups have long been fighting the central government from even before the birth of TPLF, including the Oromo Liberation Front, the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front, the Afar Liberation Front, and others.

Existentially Fractured Nation

Ethiopia is a multilingual nation, with around 80 ethnolinguistic groups, the four largest of which are the Oromo, Amhara, Somali and Tigreans. Ethiopia has rarely enjoyed stable sovereignty, either internal or external, and never before the Amhara kingdoms of northern Ethiopia (Gondar, Gojam, Shoa) were briefly united in the reign of Tewodros II in the mid-nineteenth century. Tewodros tried to centralize power after a century in which regional princes had exercised relative autonomy. He restructured the Empire’s administration and created a professional army. But he had to contend with resistance from Northern Oromo militias, Tigrean rebellions and affronts from Ottoman Empire and British-backed Egyptian forces near the Red Sea. His successor Yohannes IV in 1872 repulsed Ottoman/Egyptian expansionism (which enjoyed the support of many European and American “advisors”), pushed back Sudanese invasions in 1885–86, and contained Italian incursions to the Eritrean coast. Yohannes was killed in March 1889 by the Sudanese Khalifah Abdullah’s army.

Ethiopia in its current form began to take form during the reign of Menelik II, who was Emperor from 1889 until his death in 1913. From his base in Shewa and with the support of Shewan Oromo militia, Menelik annexed territories to the south, east and west, areas inhabited by the Oromo, Sidama, Gurage, Welayta, and other peoples. During its conquest of the Oromo, and in retaliation for centuries of Oromo expansionism, the Ethiopian Army carried out mass atrocities that included mass mutilation, mass killings and large-scale slavery. Possibly millions were slaughtered. Large-scale atrocities were also committed against the Dizi people and the people of the Kaficho kingdom. Menelik advanced road construction, electricity, education, central taxation. He founded and built the city of Addis Ababa, which became the capital of Shewa Province in 1881 and the national capital after 1889. In that year Menelik ceded control of Eritrea to Italy in return for Italian recognition of Ethiopian sovereignty (which Italy reneged on in 1935) and the supply of weapons.

While Ethiopia was never formally colonized other than by Italy, 1935-1941, its affairs have been greatly shaped by surrounding imperial activity and pressure. For example, the economy of the Red Sea region was significantly impacted by completion of the Suez Canal under Ottoman authority in 1869, by the establishment of a British base in Aden from the 1830s, later a British colony (1937-1967), and by the opening of a French coaling station at Obock on the Afar coast in 1862. Britain played off French and Italian threats to the British empire, encouraging the Italian presence in the Horn to forestall French expansion into the Nile. From 1885, Italy occupied coastal positions in Ethiopia and in southern Somalia.

The Impossible Project of Centralization

Menelik’s project of centralization was adopted in turn by Haile Selassie when he became emperor in 1916. Selassie established Ethiopia’s first-ever Constitution, inappropriately applying the Central European model of a unitary and homogenous ethnolinguistic nation-state. TIME magazine hailed Selassie as its “man of the year” in 1935, the very year that Mussolini marched on Ethiopia and Selassie fled, eschewing an ensuing two-year bloody war that included a shameful Italian massacre of 30,000 citizens and copious deployment of mustard gas. Selassie returned from UK exile and was reinstated as monarch only when the British forced out Italy in 1941.

Italy had marched on Ethiopia through Eritrea, a formal colony of Italy since 1890. Britain and France had recognized the Italian occupation (USA and Russia did not). To his credit, Selassie implemented Mussolini signature reform, the abolition of slavery, which had held between two to four million in servitude out of a total population of eleven (rising to over one hundred and ten million by 2020). Slavery of a different form, through bride abduction, continued. As late as the first decade of the twenty-first century abductions accounted for 69% of marriages in the north and as high as 91% in parts of the south. Forced relocation of peasantry has been another persistent problem.

Tigray Resistance

Tigray was central to the 1943 resistance against the return of Selassie, under the slogan, “there is no government; let’s organize and govern ourselves”. Throughout the south and east, local assemblies, called gerreb, were formed. These sent representatives to a central congress, the shengo, which elected leaders and established a military command system. To subdue the rebellion, Haile Selassie called on his patron, Britain, for aerial bombardments. Among other atrocities, thousands of civilians died in one indiscriminate attack on a market. With the British, Selassie committed many atrocities against the Tigreans. He imposed a new system of monetary taxation on the people of Tigray and continued to dismantle and reduce Tigray’s territorial boundaries in a policy of systematic marginalisation, oppression and destruction of Tigrean heritage. This led to the decline of Tigrean ethnic population and an increase in the ethnic Amhara population in Kobo and Ale-Weha. Selassie continued to work against Tigray and to weaken the power of its elites. He obliterated its economic, social, political, cultural, and linguistic development, so that it became one of the poorest and most underdeveloped regions in Ethiopia. When a famine struck Tigray in 1958 Selassie then refused to send emergency food aid. 100,000 Tigreans died. This constitutes the background to Tigrean hatred of Selassie and their contribution to his overthrow by the Marxist Derg in the 1970s.

Back to the Derg

Like Selassie, Abiy has made a grave error in messing with Tigray, made all the worse by his partnership with the wily dictator Isaias of Eritrea, whose long-term interests are quite different to those of Ethiopia. Isaias had waited two decades to get even with the TPLF for the losses he suffered in the 1998-2000 Ethio-Eritrean War. Revenge is the motive that also accounts for the participation of the Amhara elite, who had dominated the centralized administrative system of the Derg prior to 1991. Despite its opposition to the Derg, the TPLF has been a left-leaning force dominating Ethiopia’s politics for the past half a century. TPLF was founded in 1975. Its constituent associations (the Political Association of Tigreans, the Tigrean University Students’ Association [TUSA], and Tigray Liberation Front [TLF] had been established some time before. TUSA favored a national self-determination for Tigray within a revolutionary, democratic Ethiopia.

The TPLF had opposed the Derg, losing more than 60,000 TPLF fighters and suffering over 100,000 injured in the Derg’s 1991 overthrow (see below), but paradoxically represents the best of whatever socialist influence remains of that period (1974-1991). Although the Derg stood for the abolition of feudalism, promotion of literacy, public ownership of wealth, and sweeping land reform, it was also responsible for the death of hundreds of thousands of people including students, members of the royalty, wealthy individuals, dissenters, and underground opposition members. During this period Ethiopia received massive military aid from the Soviet bloc countries of the USSR, Cuba, South Yemen, East Germany, and North Korea. This included around 15,000 Cuban combat troops. The TPLF later became a major force contributing to the economic and political progress achieved in the period since, especially, under Meles.

Nobel Legacy

Long before the TPLF, the people of Tigray have played an existentially important role in the history of Ethiopia (later commonly known as Abyssinia) and its region. Around the 8th century BC, the kingdom of Dʿmt was established in Tigray and Eritrea. After the fall of Dʿmt during the fourth century BC, the Ethiopian plateau was dominated by smaller successor kingdoms. In the first century AD, the Kingdom of Aksum emerged in what is now Tigray and Eritrea. At its height, Aksum extended across most of present-day Eritrea, Ethiopia, Djibouti, Sudan, Yemen, and Saudi Arabia. Axum ranked alongside Rome, Persia, and China as one of the four great powers of the third century AD. The Aksumite King Ezana, who endorsed Christianity for the Aksumites, conquered Nubia and appropriated the designation “Ethiopians” for their own kingdom.

Abiy and the Tigray against the Derg

Abiy Ahmed had participated in the armed struggle against Mengistu Haili Mariam’s communist regime in Ethiopia (1977-1991), one of whose main enemies was Eritrea, and later served in the Ethiopian military. As prime minister he dismantled the previous ruling coalition led by TPLF, granted an amnesty to political prisoners and abolished press censorship. He also focused on empowering women. He promised free and fair elections by 2020, which he then cancelled on the pretext of Covid. Tigray’s TPLF defiantly proceeded with elections in any case, a contributory factor to the ensuing bloodshed. Abiy, like his processor Mengistu, had said he was not prepared to sacrifice national unity, yet seemed determined to do just that.

Mengistu

Mengistu had taken charge in 1977 of the Derg, the military committee established from several divisions of the Ethiopian Armed Forces that had toppled Hailie Selassie in 1974 and introduced socialism. Its elected spokesperson was General Aman Amdon. Policies included land distribution to peasants, public ownership of industries and services, and socialism. The Derg initially enjoyed great popularity under the slogans of “Ethiopia First”, “Land to the peasants” and “Democracy and Equality to all”. But poor planning and brutal suppression of dissidence, real and perceived, reduced its power against the background of the independence movement in Eritrea, and the US-backed Somali invasion of Ogaden.

Mengistu’s war with Eritrea benefited from Soviet and Israeli aid. Soviet aid came to an end under Gorbachev, followed by the dissolution of the Soviet Union itself in 1991. In the final years of Mengistu, Ethiopia abandoned socialism and prepared for a multi-party democracy.

Soviet Relations with the Derg

After rejecting a Soviet proposal for a four-nation Marxist–Leninist confederation, the Somali government launched an offensive in July 1977 against Ethiopia’s Ogaden region. Though Somalia gained control of 90% of the area, Ethiopia launched a successful counter offensive with the help of Soviet arms and a South Yemeni brigade. Somalia then broke from Soviet Union, which instead transferred its military support to Ethiopia and pushed Somali forces out of Ogaden. Moscow provided the Derg with more than $11 billion in military aid, which it used to establish the largest army in sub-Saharan Africa. Soviet support was critical in the continuing suppression of Eritrean and Tigrean separatists. The USSR established naval, air and land bases in Ethiopia, notably facilities for naval reconnaissance flights in Asmara. Economically, the Soviets provided limited credits to develop basic industries such as utilities. A significant number of Soviet professionals such as doctors and engineers also traveled to Ethiopia. Mikhail Gorbachev’s succession to power in the Soviet Union in the 1980s was accompanied by a de-ideologization of Soviet foreign relations. The Soviets pressured Mengistu to agree to face-to-face talks with Somalia’s Siad Barre, leading to a peace agreement in 1988. Following the collapse of communist regimes in Eastern Europe in late 1989 Mengistu introduced economic liberalization just as Eritrean and Tigrean insurgents were exercising significant pressure on the regime. Moscow ended military aid to Ethiopia and welcomed the USA to talks between Ethiopia and Eritrea. These collapsed when the EPRDF overthrew Mengistu in 1991.

The Development State

The new ruling coalition was led by TPLF guerrilla fighters from Tigray. In 1995 the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia was proclaimed. TPLF leader Meles Zenawi became its first prime minister (he died in office in 2012). Tigreans dominated senior ranks of government. Meles introduced ethnic federalism, allowing the country’s main ethnic groups to govern the areas they dominated.

In ironic continuation of Mengistu’s policies, Meles advocated for a strong State role in development within a context of political manipulation and suppression, inspired by the Chinese model. He accused the IMF of turning Africa into a continental ghetto. His approach included import substitution, state-sanctioned domestic capital monopolies over key imports, and local manufacturing. Chinese investments amounted to more than US $12 billion between 2000 and 2015, focusing mainly on infrastructure development including a $4 billion railway to link Addis Ababa to the Port of Doraleh in Djibouti (where China opened its first overseas military base in August 2017). In the 21st century, Ethiopia ranked among the fastest growing economies in the world – Ethiopia’s GDP per capita increased from $162 in 2005 to $790 in 2018, an average annual growth rate of more than 14 percent.

Growing or Slowing Economy

In the 21st century, Ethiopia ranked among the fastest growing economies in the world – Ethiopia’s GDP per capita increased from $162 in 2005 to $790 in 2018, an average annual growth rate of more than 14 percent. Yet the practical results of the development state have been judged mixed at best. Ethiopia remained one of the poorest countries in the world, with a per capita GDP of about $860 by 2020, whose 100 million population was predicted to double in thirty years. Poverty had declined from 45.5 percent in 2000 to 23.5 percent in 2016, even as population grew from 65 million in 2000 to 100 million 2016. Primary education (with gender parity) had reached 100 percent, health coverage 98 percent, access to potable water 65 percent, and life expectancy at 64.6 years (up from about 50 years in 2000). Foreign direct investment grew from US $265,000 in 2005 to nearly US $4 billion in 2018. Even so, wealth had become increasingly concentrated among senior party members and the military-run parastatal corporations. Elite networks alienated other factions of capital, including among the large US-based diaspora, that were not linked to the political elite. These became the base for Abiy’s free market push, couched in the language of liberal democracy.

Remembering Tigrean Supremacy

Though Tigreans made up about 5% of the population, they had benefited disproportionately under Meles’ system of ethnic federalism and the dominance of the TPLF. For example:

The government undertook two projects in Tigray. The first was the construction of terraces which, with the agreement and help of local communities, go up to the tops of the mountains at 2,500 meters. The goal was to prevent the rainfall flowing away immediately so that it could be conserved for the agricultural season. On the highest terraces were planted trees, mainly eucalyptus, the dominant tree in Ethiopia and native to Australia. These plants created a new microclimate. The terracing method was amazingly simple but required good organization. Long stretches of the fields were terraced by the villagers using stone walls from stones that erosion had brought to light. The rains eroding the still non-terraced ground formed mudslides that were held by the topmost walls, which permitted construction of a new terrace field and another wall with uncovered stones, creating new ground terraced farmland every year. Four or five years after the project commenced, almost all of Tigray, with an area only slightly less than Italy’s, was terraced.

Other initiatives included dams, reservoirs, and enclosures for regreening.

Persistence of Ethnic Conflict

Even the elections for Ethiopia’s first popularly chosen national parliament and regional legislatures in May and June 1995 were boycotted by opposition parties. There was a consequent landslide victory for the EPRDF. Ethnic conflicts have persisted to the present period, including clashes between the Oromo, who make up the largest ethnic group in the country, and ethnic Somalis. 400,000 were displaced in this conflict in 2017. Clashes between the Oromo and the Gedeo people in the south of the country created 1.4 million newly displaced people in 2018. Starting in 2019, fighting in the Metekel Zone of the Benishangul-Gumuz region reportedly involved militias from the Gumuz people against Amharas and Agaws. One group, the Fano, claimed it would not disarm until Benishangul-Gumuz Region’s Metekel zones and the Tigray Region districts of Welkait and Raya were returned to the control of Amhara Region. Two or three dozen people were killed in September 2018 in a clash between police and protestors that took place in Special Zone of Oromia near the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa. On 22 June 2019, factions of the security forces of the region attempted a coup d’état against the regional government, during which the President of the Amhara Region, Ambachew Mekonnen, was assassinated. Protests broke out across Ethiopia following the assassination of Oromo musician Hachalu Hundessa on 29 June 2020, leading to the deaths of at least 239 people.

Divisions broke out in EPRDF over how quickly to pursue political reforms in response to street protests that threatened the coalition’s grip. The protests, led by the young who account for over half of the country’s population (i.e., born after 1991), were particularly intense in the Oromo areas around Addis Adaba which had been among the most exploited and the most expropriated by new industrialization. There was little expectation of real change when Hailemariam Desalegn — Ethiopia’s prime minister since Meles’s death in 2012 — stepped down after years of unrest in February 2018, and a new prime minister, Abiy, was elected through a secret vote by the EPRDF’s opaque 180-member Council.

Neoliberal Revival/Descent

In April 2018, Abiy Ahmed, an Oromo, whose wife was a US resident, took over as prime minister, winning praise for his promises to open one of Africa’s most restrictive political and economic systems. Abiy’s agenda has been to enhance free market capitalism, reducing the role of the state while increasing the participation of Western investors and the private sector. But he would be constrained by his country’s need for long-term Chinese funding which, in the view of one analyst, promised to maintain the primacy of the state and sustain the developmental agenda of pro-poor growth within a liberal-democratic setup.

Abiy had attracted strong support from the urban middle class. He made peace with Eritrea, ended the state of emergency, and released tens of thousands of political prisoners. He invited back exiled opposition leaders and installed a former political prisoner and high-profile opposition leader as the head of the Electoral Board. He appointed a 50 percent female cabinet. He also passed amnesty laws and started the process to repeal Ethiopia’s repressive NGO law. He removed restrictions on media. He began to bring military-run parastate organizations under government control. As part of a reform aimed to deepen and strengthen administrative decentralization, woredas or local representative councils were reorganized, and new boundaries established to better cater for the growing number of smaller towns and their increasing populations, so as to help them provide a wider range of services, such as markets and even banks. 21 independent urban administrations were added and other boundaries re-drawn, resulting in an increase from 35 to 88 woredas in January 2020.

Tigreans complained that they were being persecuted in a crackdown on corruption and past abuses. Ethiopia’s new goal under Abiy has been for Ethiopia to reach lower-middle income status by 2025 through sustained economic growth. The state had been heavily engaged in the economy, previously, in such key sectors as telecommunications, financial services, aviation, logistics, railways and power distribution, and the country’s growth was largely driven by state-run infrastructure development. Debt load was a concern, and the IMF’s ratings for Ethiopia changed from moderate to “high risk of debt distress” in May 2018. Ethiopia’s growth has been marred by high inflation and a difficult balance of payments situation. Inflation surged to 40% in August 2011 and was 20% in 2020.

On June 5, 2018, Ethiopia’s ruling party announced that state-owned enterprises, including the railway and the sugar corporation, would be partially privatized while Ethiopian state-owned monopolies in the sectors of aviation, telecommunications, and logistics would be opened to the private sector through the sale of minority shares. The Homegrown Economic Reform Plan advocated an increased role for the private sector, promising deregulation to improve Ethiopia’s ranking on the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Index. The USA welcomed growing opportunities for US trade and investment, particularly in manufacturing, energy, and agricultural processing. The World Bank approved US$ 1.2 billion in grants and loans in return for the standard package “towards supporting reforms in the financial sector including improving the investment climate.” The German president and key German industrialists signed an MOU between the Volkswagen Group and the Ethiopian Investment Commission to set up an automotive industry in Ethiopia. Inequality was expected to increase given that low wages are seen as Ethiopia’s “comparative advantage” with the average wage of workers in the leather factories, for example at US $45 per month compared to the minimum wage in Guangdong at US $300. The recent Worker Rights Consortium’s investigation has revealed that Ethiopian factories paid wages far lower than in any other apparel-exporting countries, with an average of 18 cents per hour. Western governments have encouraged Abiy to allow access to the formal economy of refugees so as to reduce the pressure of refugees on the European economies.

Conclusion

The ascent to power of Ethiopia’s Prosperity Party signals the continuation of overlapping struggles between (1) agendas of power and centralization under the guise of “modernization” of one kind or another, responsive to the interests of international capital, against agendas of ethnic identity, autonomy, and regional capital, and (2) agendas of State developmentalism, against agendas of neoliberalism. Some important economic improvements notwithstanding, the results are persistent conflict, suffering, poverty, and authoritarianism amidst increasing inequalities of income, gender, class and ethnic status, and constant great power competition for strategic advantage in the expropriation of Ethiopian wealth.