Does India’s Return to Kabul Run Through Vladivostok?

Russia ideally hopes to broker a rapprochement between the Taliban and India in order to restore the latter’s influence in Afghanistan and thus balance out Pakistan’s existing influence in the country as well as China’s emerging influence there. The Kremlin would likely do this without any extra incentive since it aligns with its envisioned 21st-century grand strategy of becoming the supreme balancing force in Eurasia but it wouldn’t hurt if India invested a little bit more in the Arctic and Far East in order to encourage this potential outcome.

The special and privileged strategic partnership between Russia and India remains a priority focus for both Great Powers but has yet to diversify from its dependence on military cooperation. The two cooperate very closely in international fora and share near-identical stances towards most issues of significance (apart from Afghanistan most recently), but they’ve struggled to add a serious economic dimension to their ties. This isn’t for lack of trying, though, since it’s attributable to objective reasons.

The Russian economy became disproportionately dependent on resource exports after the USSR’s collapse while India’s semi-socialist economy at the time gradually liberalized and thus became more important to Western countries. As Moscow looked inward, New Delhi looked outward, and there appeared to be little common ground between their economies other than the legacy of their military and nuclear energy cooperation. That’s finally beginning to change, however.

President Putin’s National Development Projects aim to diversify the Russian economy from its hitherto disproportionate budgetary dependence on resource exports through a bevy of investments in a slew of domestic industries such as construction, transportation, education, and cutting-edge technology among many others. His country aspires to balance between its Eastern and Western partners, which for all intents and purposes presently refer to China and the EU, by pioneering new opportunities along the Southern vector.

India is Russia’s priority partner in this cardinal direction, and the two sought to enhance bilateral trade through the North-South Transport Corridor (NSTC) via Iran and Azerbaijan. That project failed to fulfill the initially lofty expectations held of it primarily because New Delhi decided to abide by Washington’s unilateral sanctions regime against the Islamic Republic. February’s agreement to build a Pakistan-Afghanistan-Uzbekistan (PAKAFUZ) railway also stands to make the NSTC redundant for Russia once peace returns to Afghanistan.

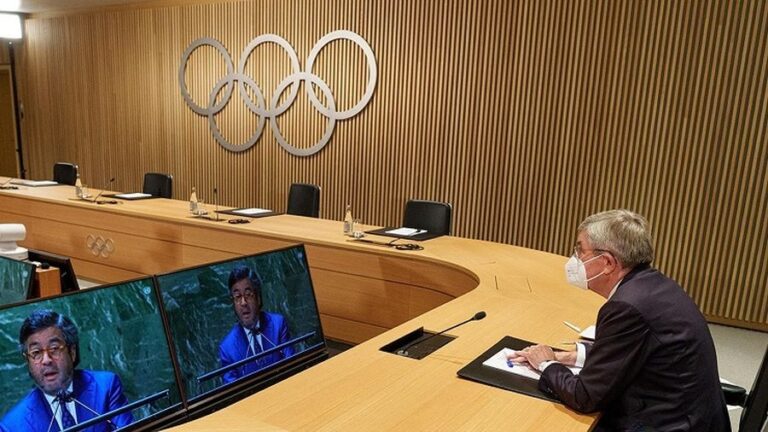

Prior to this year’s events, Russia and India unveiled the Vladivostok-Chennai Maritime Corridor (VCMC) during the 2019 Eastern Economic Forum (EEF) in Russia’s Far East city when President Putin hosted Prime Minister Modi as his guest of honor that September. This opens up a new avenue for economic cooperation between the two. Since then, India has also expressed interest in investing in Russia’s Arctic and Far East energy projects, but they still lack any meaningful commercial ties.

This year’s EEF from 2-4 September might change that. Indian media reported that their country will have a strong presence at the event, which is keeping in tradition. There’s also interest in hosting a trilateral Russia-India-Japan meeting seeing as how that East Asian participant is the South Asian one’s strategic partner too. India can help Russia develop its far-flung, sparsely populated, but resource-rich and geostrategically positioned region both due to its objective-self-interest in doing so but also potentially as a quid pro quo elsewhere.

To explain, India suddenly lost all of its influence in Afghanistan after the Taliban’s rapid takeover of the country in early August. New Delhi refused to publicly talk with the group before then and therefore was ineligible to participate in the Extended Troika between China, Pakistan, Russia, and the US for managing the highly dynamic situation there. The problem is that India already invested over $3 billion in development projects in that country and presently has no means of ensuring their security, let alone building upon them in the future.

Meanwhile, Russia has surprisingly emerged as the country with more influence over the Taliban than anyone else apart from Pakistan despite still officially designating it as a terrorist group. This was the result of years of diplomatic investments that included hosting the Taliban in Moscow for peace talks. Russia ideally hopes to broker a rapprochement between the Taliban and India in order to restore the latter’s influence in Afghanistan and thus balance out Pakistan’s existing influence in the country as well as China’s emerging influence there.

The Kremlin would likely do this without any extra incentive since it aligns with its envisioned 21st-century grand strategy of becoming the supreme balancing force in Eurasia but it wouldn’t hurt if India invested a little bit more in the Arctic and Far East in order to encourage this potential outcome. After all, it’s also in India’s objective self-interests to do both: invest more in Russia’s Asian regions in order to balance Chinese economic influence there in parallel with restoring its influence in de facto Taliban-run Afghanistan with Russian help.

The continued economic diversification of the Russian-Indian Strategic Partnership during the upcoming EEF could therefore reap dual strategic dividends for New Delhi in two extremely important parts of Asia: the Russian Far East and eventually Afghanistan. All that’s required is for Indian strategists to ascribe to this vision and for their decision makers to have the political will to carry it all out. Success in the Far East would balance Chinese influence there in a non-hostile way while the Afghan front might lead to Chabahar’s revival with time.

These observations make the upcoming EEF more important than ever for Indian grand strategy. New Delhi can leverage its economic influence to further incentivize the Kremlin to lend it a helping hand in Kabul. The earlier mentioned outcomes would be mutually beneficial because they’d successfully diversify their strategic partnership by incorporating a long-overdue economic dimension to it and thus comprehensively strengthen their ties. It’s therefore incumbent upon India to make the best of this opportunity if it so chooses.