The Russian-Israeli-Iranian Conundrum in Syria

More often than not in life, there is a simple explanation. But speculation has a habit of taking flight because of its seductive appeal.

The visit by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to Moscow on May 9 and his meeting with President Vladimir Putin has fueled rumors that the two struck a Faustian deal allowing Tel Aviv a free hand to destroy Iran’s Quds Force and Iran-backed militia deployed to Syria.

Such speculation arose due to two reasons. One, immediately after Netanyahu’s return to Tel Aviv, Israel launched its biggest air strike on enemy targets anywhere in the world since the 1973 Yom Kippur War when 30 Israeli jets attacked bases in Syria on May 10. And, like in the Sherlock Holmes story where the dog didn’t bark, Moscow refrained from reacting.

Two, Russian media reported the following day that Moscow would not transfer the advanced S-300 missile defense system to Syria after all. Now, doesn’t that imply that Putin had a rethink after the talks with Netanyahu on May 9?

But, consider the following. Moscow was aware that the Israeli attack on May 10 was provoked by a missile attack on the Golan Heights from Syrian territory and that it was in retaliation for the Israeli attack on Syrian bases on April 8, which killed seven Iranian personnel.

Simply put, Moscow passively watched dozens of missiles rain back and forth on April 8 and May 10 and had no reason to apportion blame to either side. Its silence was deafening.

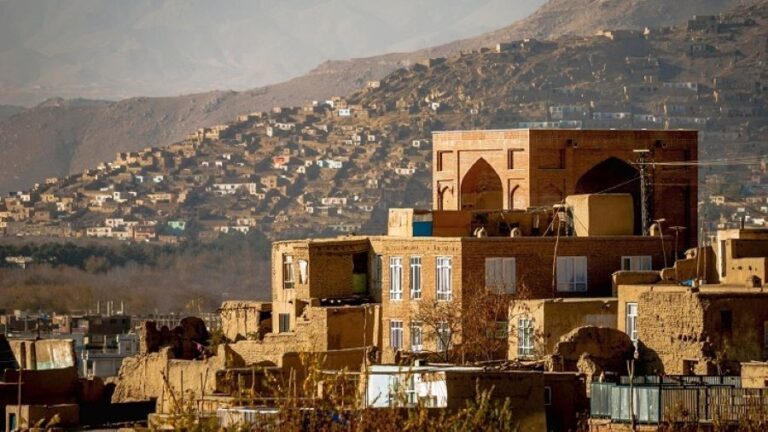

Syria’s air defense system

Quite wisely so, because Russia does not want to get entangled in what should strictly remain a Syrian-Iranian brawl with Israel. Period. On the other hand, the Russian Defense Ministry carefully monitored that about half of the 60-odd missiles fired by the Israeli jets were shot down on May 10, which of course meant two things.

One, the Syrian air defense system is once again proving its mettle – according to the Russian Defense Ministry, the Syrians shot down more than 70 of the 130 missiles fired by the US, UK and France during the April 14 air strike.

Two, stemming from the above, Moscow assesses that any major upgrade of the Syrian air defense system can be put on hold for the present.

Moscow is on record as saying that if an emergency situation arises, Russia will be in a position to transfer S-300 missiles and launch pads to Syria in short notice in about a month’s time. Theoretically, such a situation arises if Syria again faces the threat of a Western attack. But there are no signs of such a thing happening in the near-term.

Unsurprisingly, the Kremlin came down hard on speculation that its decision not to transfer S-300 missiles to Syria was at the behest of Netanyahu. Presidential spokesman Dmitry Peskov flagged on May 11 that Moscow’s decision predated Netanyahu’s visit. And TASS gave a detailed explanation that there never was a concrete decision in the first instance to supply Syria with the S-300s and, therefore, the question of scrapping any decision simply does not arise.

Evidently, at the root of all this wild media speculation is an unseemly haste to give a spin that Putin is “pro-Israeli.” But it is really a clumsy attempt. The point is, the Russians are not one-dimensional men.

Russian diplomacy has a great tradition of juggling many balls in the air. Russia manages its friendly relations concurrently with China and Vietnam, Turkey and Greece (and Cyprus), Iran and Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Egypt, Iran and Jordan and so on – and in a conceivable future, probably India and Pakistan as well.

Simply put, what Iran can give Moscow, Israel cannot – and vice versa. Moscow wants good relations with both Iran and Israel, because they serve different purposes in Russian foreign policy. Having said that, Russia does not subscribe to what Iran calls the “resistance front” in Syria.

But then, Russia also appreciates that Iran and Hezbollah’s presence in Syria is at the invitation of Damascus and is critically important in the fight against the extremist groups. Quite obviously, Russia refuses to share the Israeli perceptions of Hezbollah as a terrorist group. If anything, the results of the May 6 election in Lebanon would only reinforce the Russian belief that Hezbollah is a legitimate political force to be reckoned with.

The many contradictions

Clearly, in these complex circumstances, it is unrealistic to expect Russia to be party to any Israeli agenda to vanquish the Iranian and Hezbollah presence on Syrian territory. On the other hand, Russia will also not oppose Israel or Syria’s need to safeguard their respective security interests and/or act in self-defense.

Thus, while Russia criticized Israel for its April 8 missile attacks on Syria, which triggered the present action-reaction syndrome, by calling it a dangerous move, it refused to get excited about either the retaliatory missile attack on Israel from Syria on May 10 or the swift Israeli counter-attack on Syria soon after.

But the contradiction goes beyond this. The point is, Russia also has a congruence of interests with Damascus and Tehran in preserving the unity of Syria and in strengthening its national sovereignty. Russia, therefore, cannot condone external parties attempting to balkanize Syria or to impede Damascus’ drive to regain control of the entire country.

It follows logically that Russia will help the Syrian armed forces to develop the capability to stabilize the situation within that country. Quite obviously, Russia believes that it is Syria’s sovereign prerogative to develop the power of deterrence – just like Israel or Lebanon in the region.

What cannot be overlooked is that even without Russia’s S-300 missiles, Syrian air defense capabilities will continue to be upgraded with outside help, including Iranian help. Perhaps, this is already happening and Moscow must be aware of it too while making the considered assessment that at present there is no requirement to dispatch S-300 missiles to Syria. After all, nothing concerning the military balance in Syria escapes Russia’s notice.

Suffice to say, the Kremlin readout of the conversation between Putin and Netanyahu in Moscow on May 9 takes the breath away. One cannot recall Putin speaking with such effusive warmth at a personal level with a foreign leader in recent times – not even with Iranian leader Hassan Rouhani or Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad, who are Moscow’s key allies. This is Russian diplomacy at its best in very trying times.