Epic Drama – Is Tim Sweeney’s Attack on App Stores a Case of Unreal Narcissism or Something Else?

On August 6th, 2020 President Trump issued an executive order barring transactions with WeChat or its parent company Tencent Holdings, Ltd. See here.

Tencent owns 48% of Epic Games, from a $330M investment in 2012, with the rest being largely owned by company founder and CEO, Tim Sweeney.

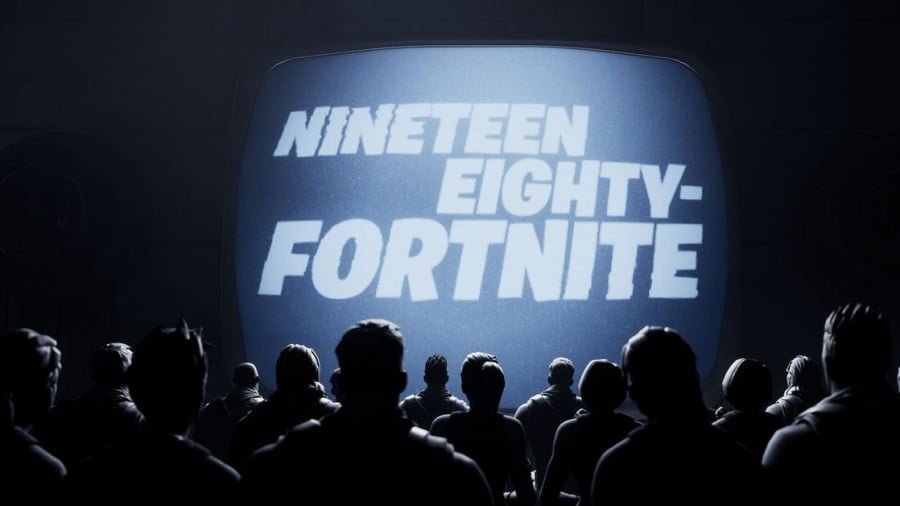

On August 13, 2020, Epic Games chose to take a provocative action by offering a direct payment option in its Fortnite app, in clear violation of Apple’s App Store and Google’s Google Play Store policies.

Epic did this not in an app update, but by changing code that had already been approved in the app stores. Epic has since been expelled from both app stores and has filed suit against Apple and Google for anticompetitive behavior.

Sweeney & Epic have provoked a battle royale with Apple & Google. Is it really a David & Goliath quest to benefit the consumer, undertaken selflessly by Epic? There is a lot more to the story.

Developers, Romans, Countrymen

Some of you may remember a sweaty Steve Ballmer, then COO of Microsoft, galloping around a conference stage screaming “Developers, developers, developers!” If you don’t, you can see a clip here (Warning: not for the faint of heart).

This took place at a Microsoft Developers Conference and Ballmer was trying to entice programmers in the audience to begin developing for the soon to be released Windows 2000.

Software development requires division and coordination of labor. If every programmer had to write their entire program from scratch, there would be much less software in the world. Modern software is a collage of many people’s work. How that work is monetized is dependent on its function and who wrote it.

When you use a program on your computer or phone, a lot of the functionality actually comes from the operating system vendor. The developer(s) of the app you’re using can easily include the familiar elements of the OS by using vendor-provided tools from a Software Development Kit (SDK).

Large operating system vendors like Microsoft, Google and Apple make these SDKs available along with integrated development environments. From their point of view, anything that encourages people to write for their platform is a loss leader that supports their overall OS platform business.

A lot of this actually dates back to the days of the monkeyboy dance, as Ballmer’s soggy terpsichorean spectacle is commonly known in the industry.

Beyond ways to include basic UI elements like windows and text boxes, SDKs include specialty APIs and libraries are available to support things like graphics performance improvements that would be too labor intensive for the individual developer to tackle.

SDKs and APIs bring functionality that is ready to use. It is work the developer doesn’t have to do. They can instead focus on writing code to support the unique purpose of their application. In the broader software world, vendors often charge other developers for access to APIs, as the features they provide can really speed development or provide a high level of functionality or compatibility.

In mobile game development, developers use these tools to create the apps you use, which are then submitted to Apple or Google for publishing in their respective app stores. Before the app bundle is made available to you, it is scanned for known malware or for the use of restricted methods that could constitute a security risk.

Mobile OS vendors have a unique role to play in stopping the proliferation of mobile malware and exploits, but the current mood is hostile towards them due to the pricing models they have used. Both Google and Apple take 30% of the revenue from the price chosen by the developer.

The iPhone Has Landed

So, how did we get here?

When the iPhone was first introduced, there was no app store. Apple knew it wanted to encourage an app ecosystem, but also knew the risks of allowing unrestricted applications on a device that could monitor phone calls and the user’s location.

Mobile phone malware was already in existence and then market leader Blackberry’s competitive advantage was its platform security. So Apple made device security a key product focus of the iPhone.

The initial product positioning of iPhone was a mobile phone that doubled as an iPod and had a web browser. Initially, the only way developers could reach the iPhone user base was with a sort of web application called a “web clip,” basically what we call a mobile-optimized website today.

A year and a half later brought the App Store, which launched as part of iTunes, drawing on Apple’s immense installed base of iPod users. This decision made marketing an app similar to marketing a song which brought pricing of applications way down.

With this move, Apple forced a new pricing model on the software industry, which also allowed for massive scale of distribution. This had the potential to open the market to individual developers like never before. But first Apple had to solve a major problem.

Small software developers, often individuals not companies, would have to maintain a website, a code repository to track versions and apply and qualify for a credit card merchant account. Further, due to credit card industry pricing models, each sale would be subject to per transaction fees. A $1 app would rack up close to $.39 in merchant fees, before the costs of maintaining a website, active user database or the opportunity cost of management time were even considered.

As a value proposition, 30% was a reasonable fee for apps in the $1-3 range that Apple was trying to focus development. This allowed a way to sell cheap software and remove the immense management hassle for small developers. It also made many small developers rich and eventually paid out billions in revenue.

The App Store also created a curated model for software distribution that would prevent malicious developers from installing malware on a user’s phone.

Google would copy most of Apple’s approach in its creation of the competing Google Play Store for Android.

Epic Nonsense

Today many app developers, such as subscription streaming services, are balking at paying 30% to access their customer bases on mobile, especially if those customers are adding already existing accounts to a new mobile device.

Epic CEO Sweeney may certainly have a point that 30% is too high a cut for Apple and Google. But what is the right price to host apps, validate they don’t contain malware, provide massive bandwidth, stand up a Content Delivery Network (CDN) to deliver the application bundles on demand to millions of users, charge the user’s credit card, manage chargebacks and maintain a versioned repository? It’s hard to determine the right rate for what an app store provides, but that service is worth something. Sweeney is on record saying that he thinks app stores could charge as little as 8% and still make a profit.

If there is an antitrust case to be made against Apple and Google for maintaining “control” of their mobile app stores, where developers can pick any price they want, it is not likely to be won by Epic.

This is because Epic agreed to be contractually bound by the terms & conditions of the app stores and then pulled a stunt designed to provoke a legal action. It did this by deploying a “hotfix” to the code, avoiding review by Apple or Google, who would have rejected its changes as against the license terms.

Where Epic made its biggest error was in how it changed the selling price of its in-app currency for Fortnite, V-Bucks. Previously, 1,000 V-Bucks were $9.99, which after Apple or Google’s 30% cut, yields $6.99 to Epic. Courageous Epic, in dogged defense of its aggrieved userbase, reduced the price to $7.99.

And they took that payment directly, yielding an extra dollar of revenue to Epic. Somehow this fact has been left out of the coverage. All of this noise in the tech press and no one notices that Epic was trying to squeeze an extra 14% out of Fortnite players.

So not only does Epic value Apple & Google’s hosting and access to millions of customers at zero, it decides to take another buck for good measure.

This is going to bite them in their court case because it completely undermines the whole presentation of facts. It is stupefying they didn’t just cut out the Apple and Google fees and claim they were just trying to benefit the consumer. By going after an extra dollar, Epic destroys its own argument before the case even begins.

Not only is their presumably competent counsel simultaneously suing Apple and Google for the same “monopoly” behavior but now they have to justify how Epic taking money from the monopolists helps the consumer.

As Mona Lisa Vito (Marisa Tomei) said in My Cousin Vinny, “Wait, there’s moah!”

It’s relevant to bring up that Epic already runs an app store for PC and Mac games (The Epic Games Store). It uses the exact same business model, copied from Apple and Google. Game developers make use of libraries and APIs that govern the physics and motion of the characters, ships, etc. Epic developed a game engine in 1998 for a game called Unreal and then released the underlying Unreal Engine for other game developers to use. Epic monetizes and charges game developers 5% of their revenues for using it.

It’s obvious that Epic wants to have all its games, as well as all games developed using its Unreal Engine, on all platforms, in its app store.

Android users can install apps on their phones from anywhere, while Apple protects its users within its “walled garden.” Apple, who has close to 60% market share in mobile in the US, also prevents developers from leaving a sandbox and prevents them from having root access on your iPhone.

It’s possible that notoriously demanding Epic thinks it can force a special deal out of Apple and then Google will follow suit. Then Fortnite can rejoin the mobile app stores and Epic could conceivably extract licensing revenue from its Unreal Engine licensees after they paid their app store fees to Apple and Google.

But it sure seems like Epic is trying to set up a mobile app store, for all games using the Unreal Engine, so it can do exactly what Apple and Google do. To do this, they need to destroy the app store economy as it currently exists and they want to use the antitrust provisions of US law to do it.

This will mean that the courts would mandate that phone vendors, but particularly Apple, would have to allow sideloading of any app from any source. This seems like consumer freedom, but actually brings a lot of risk, far beyond just to the individual app user.

The most charitable interpretation of Epic’s actions is that it wants to start a competing mobile app store without supervision by Apple & Google. It wants to do this because of the incredible number of games that are developed using its Unreal Engine.

Since being kicked out of the app stores, Epic has begun offering direct downloads of the Android version of Fortnite from its website. Epic may be willing to forego all revenue from Apple customers on iOS and macOS in pursuit of its larger goals.

The problem is that Epic didn’t have to do what it did, and its stunt is unlikely to prevail in court. More troublesome is that it appears that Epic is willing to harm Apple for no real benefit to itself. It’s almost like forcing open iOS to software installation outside the App Store is the actual goal, not an economic leveling.

It’s also interesting that Sweeney, with an estimated net worth between $5-12B, feels a need to extract an extra 14% from his Fortnite customer base. Notably, Sweeney owns over 50% of Epic’s equity, with the rest held by Tencent. This means that an increase in privately held Epic earnings largely flows directly to Sweeney and Tencent as dividends.

Perhaps Sweeney is less Don Quixote than he portrays, and more Scrooge McDuck.

The China Shop

In the world of COVID-19, Apple and Google have implemented a set of interoperable COVID-19 contact tracking APIs. These are now running on basically every phone in the United States. It is especially concerning to imagine how focused the Chinese Communist Party will be on implementing malware that can exploit these private APIs to track individuals or groups. Google and Apple will tell you it is impossible for an unauthorized app to access your private location and contact tracing data but the nature of exploits is that workarounds are always found.

Simply put, if the code running on your phone has never been audited by Apple or Google, there is no realistic way to know if it is accessing their private API calls, such as the COVID tracking functionality.

The inclusion of rogue code in a game engine, for instance, would create a profound threat to millions of users. Coupled with personnel data stolen by a hostile actor, it would create a realtime target tracking system.

This is exactly what Trump’s executive order is meant to prevent.

China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) breached four million records in the United States Office of Personnel Management in 2015, 145 million records of American citizens from Equifax in 2017 and constantly targets US military service records.

While Android malware is prevalent if the user installs an app from an untrusted source, 60% of US mobile users are on iOS and thus can only download software from Apple’s App Store.

Making it easier to install unaudited software on iOS devices would make the PLA very happy, especially in conjunction with all the stolen private details of Americans they already have.

We leave it to the reader to decide if it is interesting, or worrying, that a company half owned by Tencent Holdings, Ltd. (which works closely with the CCP & PLA), is choosing to lead a battle to destroy the app store economy. Epic took this action almost immediately after the Trump administration named its largest investor as a threat to national security.

The business case for a third mobile app store may be harder to make when it requires opening so many Americans to Chinese malware.

Now the clock is ticking, and it may soon be sweaty Sweeney’s turn to dance.

Tik Tok.