The Machiavellians: James Burnham’s Fascist Italian Defenders of Freedom

In our attempts at understanding such people who view themselves as the natural ‘ruling elite’, it is important that we never take a literal approach in our attempts to understand their desires and thus their motives.

“[James] Burnham…the real intellectual founder of the neoconservative movement and the original proselytizer, in America, of the theory of ‘totalitarianism’.”

– Christopher Hitchens, For the Sake of Argument: Essay and Minority Reports

[The following is the second installment from one of the chapters from my book “The Empire on Which the Black Sun Never Set: The Birth of International Fascism and Anglo-American Foreign Policy” which will be made freely available as a three part series published via SCF. For Part 1 of this series refer here.]

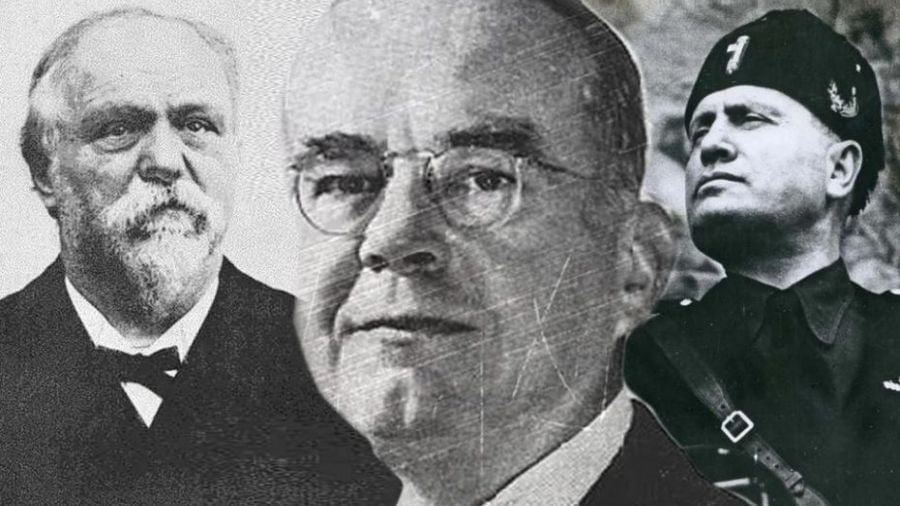

In an interview with Washington Post columnist Mary McGrory in 1950,[1] Burnham described the new narrative he was to give to the masses to explain the new face he had chosen for himself. The Virgil to his Dante, had become Machiavelli, which he credited for his new ‘revelations’ in his The Managerial Revolution. This made for a very convenient segway to the ‘modern Machiavellians’ of his day. Robert Michels, Vilfredo Pareto and Gaetano Mosca, who referred to themselves as the “Machiavellians.” Georges Sorel, who had influence over this group would also have great influence on Burnham who revealingly gushed over Sorel in his follow-up book The Machiavellians, Defenders of Freedom (1943).

What linked the Machiavellians first and foremost, was their belief in the possibility of a ‘science’ of society.[2] Second, they believed in the nonrational in politics and that ruling classes were governed by a ‘political formula’ which presumed a nonrational belief, such as the concept of the ‘divine right of kings’ or the ‘sovereignty of the people’, that was intended to justify their power.

Burnham first read the Machiavellians in the 1930s at the urging of Sidney Hook, who supposedly wanted to introduce Burnham to intelligent criticism of Karl Marx. In 1972 he told Charles Lam Markmann that before he had discovered the Machiavellians he had not been significantly influenced by any other political theorists.[3] Because of the influence of the Machiavellians, Burnham claimed he had come to understand “more thoroughly” something he had long known only intuitively that “only by renouncing all ideology can we begin to see the world of man.”[4] One could also say that Burnham’s full thought would have gone something like this: “And thus by renouncing all ideology, we are free to use it as we choose. Those who can see through ideology, but can use it successfully to manipulate the masses, will in turn become their God.”

Thus, in our attempts at understanding such people who view themselves as the natural ‘ruling elite’, it is important that we never take a literal approach in our attempts to understand their desires and thus their motives. For if you do, then you will always become lost in the tangle of meaningless values, morals and reasons they have given for what they do. It is simply a veil one changes in and out of, to fit the audience one is speaking to.

Since Burnham so openly confessed that these men are among the titans that influenced his thinking, taking a closer look at these men’s allegiances and actions in life is worth our time.

Georges Sorel (1847-1922) was a collaborator of Charles Maurras’s Action Francaise, which was pro-Vichy government who had collaborated with the Nazis during the war. Recall that Maurras had been a great influence on the younger Burnham through the writings of T.S. Eliot. Sorel, who started out Marxist, became a supporter of Maurrassian integral nationalism beginning in 1909, and created the ideology Sorelianism, a revisionist interpretation of Marx according to Sorel.[5] Recall that Burnham and Hook had also attempted to revise Karl Marx. This is likely the real reason why Hook recommended Sorel as reading for Burnham in the first place.

In many ways, Sorelianism is considered to be the precursor of fascism.[6] Upon Sorel’s death, an article in the Italian Fascist doctrinal review Gerarchia edited by Benito Mussolini and Agostino Lanzillo, a known Sorelian, declared “Perhaps fascism may have the good fortune to fulfill a mission that is the implicit aspiration of the whole oeuvre of the master of syndicalism: to tear away the proletariat from the domination of the Socialist party, to reconstitute it on the basis of spiritual liberty, and to animate it with the breath of creative violence. This would be the true revolution that would mold the forms of the Italy of tomorrow.”[7] Many Italian fascists were Sorelians. Sorel would become famous for his concept of “the power myth,” which presumed that only through power, not formal law or high ideals, can one restrain another’s power over you. Sorel’s ‘power myth’ heavily influenced the Machiavellians.

This again explains why the fascists were calling themselves national socialists, it was a ploy to radicalise socialists into their camp. Very much along the lines of what Burnham was doing in the United States, a Trotskyist French-Turn. It was just that many leading Trotskyists were in fact working for the fascists…

Robert Michels (1876-1936), was a friend and disciple of the sociologist Max Weber. Born in Germany but later moving to Italy, he politically moved from the Social Democratic Party of Germany to the Italian Socialist Party, adhering to the Italian revolutionary syndicalist wing and later to Italian Fascism, which he saw as a more democratic form of socialism. He became a member of the National Fascist Party of Italy in 1924 and remained a member until his death. Michels was convinced that the direct link between Benito Mussolini’s charisma and the working class was in some way the best means to realize a real lower social class government without political bureaucratic mediation.

Vilfredo Pareto (1848-1923) welcomed the advent of fascism in Italy and was honored by the new regime. Pareto had argued that democracy was an illusion and that a ruling class always emerged and enriched itself. For him, the key question was how actively the rulers ruled. For this reason, he called for a drastic reduction of the state and welcomed Benito Mussolini’s rule as a transition to this minimal state so as to liberate the ‘pure’ economic forces.[8] Mussolini had in fact attended Pareto’s lectures as a student at the University of Lausanne. It has been argued that Mussolini’s move away from socialism towards a form of ‘elitism,’ a hallmark of the Machiavellians, may be attributed to Pareto’s ideas.[9]

Although Gaetano Mosca’s political career looks tame in comparison to his peers, he also maintained Sorel’s ‘power myth,’ which presumed that only through power can one restrain another’s power over you. This is very much the doctrine of Gorgias, a well-known ancient Greek sophist, whom Socrates battled in Plato’s dialogue Gorgias. In the doctrine of Gorgias, sin is equated with powerlessness and the good is equated with abject power. Thus, the tyrant is the most good and the slave the most sinful in such a view.[10] Burnham was an open critic of Plato for obvious reasons.

Burnham wrote The Machiavellians in high praise of these men. The book made the argument that a choice had to be made between Machiavellian realism (facts, empiricism) and idealism (illusions, ideology).

Burnham’s ‘Struggle for the World’ à la British Intelligence

Burnham’s remark in 1972 that no one had influenced him significantly since the Machiavellians was not wholly true. In the mid-1940s, as his anxiety about the Soviet communist threat mounted, he turned for broader perspective on the problem to two thinkers, British historian (and fellow Balliol man) Arnold Toynbee and geopolitical analyst Halford Mackinder, who during the years of the war had seized the attention of places such as the Institute for Advanced Studies at Princeton and Yale’s Institute for International Studies.

In Toynbee’s A Study of History whose first six volumes had come out by the mid 1940s, he outlined the progression of 21 civilisations which at various points along their trajectories, had all suffered periods of breakdown, what Mackinder referred to as “Time of Trouble”. In each case study, the civilization in question regained stability through the intervention of a geographically peripheral and culturally primitive power that had restored order by imposing a “Universal State.” So, it was with rough hewn Rome which had brought peace to the culturally superior but chronically strife-torn Hellenistic world. Toynbee’s theory of civilizational breakdown and recovery made a strong impression on Burnham.

Mackinder first expounded his ideas at length in a 1919 work titled Democratic Ideals and Reality: A Study of Politics of Reconstruction. According to Mackinder, if the Heartland were “under a single sway” that also possessed “invincible sea-power” that state would have world empire and have “the ultimate threat to the world’s liberty” within reach. The key to control of the Heartland was control of Eastern Europe “Who rules Eastern Europe commands the Heartland…Who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island: Who rules the World-Island commands the World.”

Mackinder’s 1919 answer to the threat of a Heartland-based adversary had been a counterweight in the guise of a British Empire remodeled into a world league of democracies (aka The League of Nations). However, by the 1940s he had come to envisage the North Atlantic countries as the basis of his democratic league since the United Nations had been formed around the principles of the League of Nations, upon Roosevelt’s death and contrary to his intention. [11]

Burnham first revealed his debt to Toynbee and Mackinder in a paper he wrote in 1944 that he could not then publish. This was a study of Soviet aims he produced at the request of the OSS wartime forerunner of the CIA. In 1947 he published the paper in full as the first section of a book he had written on Soviet ambitions.[12] He called the book The Struggle for the World.

The Truman Doctrine had been announced in March 1947, in response to the request for aid for Greece, which Britain had claimed had fallen into a communist triggered civil war. “It must be the policy of the United States” Truman told Congress, “to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.” The Truman doctrine marked a major turning point in U.S. foreign policy; the abandonment of non-intervention abroad in time of peace for the role of world sentinel against claimed Soviet expansion.

Burnham’s The Struggle for the World was published less than one week after the announcement of the Truman Doctrine.[13] His book opened with the study he had done for the OSS, which of course was not publicized as the case, which happened to be an analysis of Greece’s so-called ‘civil war.’ What fortuitous timing! He writes that Greek soldiers have mutinied from the British Mediterranean Command saying, “We do not know the details of what happened in the mutiny; but the details, important as they might be for future scholars, are unnecessary…The munity was led by members of an organization called ELAS… ELAS was the military arm of a Greek political grouping called EAM…EAM was directed by the Greek Communist Party…from its supreme headquarters within the Soviet Union. Politically understood, therefore, the Greek munity…and the subsequent Greek Civil War, were armed skirmishes between the Soviet Union, representing international communism, and the British Empire.”

It is interesting that Burnham says that the details are not necessary except for future scholars. Well, the details today are known, and the true story behind this so-called Greek Civil War could not be further than what the British Empire, American intelligence and Burnham were claiming. As already discussed in detail in Chapter 6, it was British soldiers who in fact turned on ELAS in 1943, while they were fighting the Nazis, on the orders of Churchill. ELAS had successfully defeated the Italian forces, and Germany had entered to conquer Greece which offered an important geopolitical foothold, and as we have seen from Chapters 6 and 11, became a center for Operation Gladio. Churchill was fearful that ELAS was also going to beat the Nazis. The greater majority of the Greek people supported the political group EAM, and they had earned the love of the people through their valiant defense of their country.

Churchill did not want a pro-communist government in Greece but rather a pro-monarchy government, to which he directly intervened and reinstalled the Greek fascist king George II. Britain, who was having a hard time containing the Greeks called for American back-up. The Americans did not fight man-to-man but waged chemical warfare on the Greek people who so bravely defended their country against fascism. After years of valiantly fighting, the Greeks finally succumbed, and Greece became a Gladio center of terror. It was not a Greek Civil War but a cowardly attack on the independence and freedom of the Greek people by the pro-fascist Anglo-American forces.

You can understand why Burnham thought the details of this tragic story unimportant…

The American people had been lied to as they are lied to today, to justify the unjustifiable, the unleashing of offensive warfare in the name of security and peace. The Truman Doctrine opened the door to a 75-year ‘War on Terror’ that has continued to this very day. It gave the American government the so-called ‘right’ to militarily intervene and wage clandestine warfare on any country it selected. As we have come to see time and again, we are told the details are never important in the moment that such interventions occur, and by the time scholars get around to it, the damage has long been done. However, the pattern has remained the same over the course of the past 76 years, and thus we, the collective West, are responsible for these crimes if we remain silent. For we should know by now that such unilateral acts of carnage on innocent people have never been justifiable. We are not the bringers of freedom, but rather are the aiders and abiders of doom and the very destroyers of freedom.

We have become the servants to the monster we claim to be saving the world from.

Burnham used his OSS fluff piece, The Struggle for the World, to call for, just as Bertrand Russell was doing at the time, a pre-emptive strike against the USSR[14] while America still enjoyed the sole monopoly over the nuclear bomb.

America had only a short window where they would be the sole possessors of such a titanic force, and the neo-breed of war hawks and neocons believed that the United States owed it to the ‘free people’ of the world to bomb the USSR into the stone age. Burnham would argue that the winner in this arms race would also achieve world empire in the sense of “world dominating” political influence. Both countries might be destroyed in the course of the contest – “but one of them must be.” Burnham thus posed the question to the America people, would America have “the will to power?”

However, if the USSR were to be bombed, that would not be the end. Burnham put forward the thesis that the U.S. would have to make victory not peace its supreme aim. It must disregard such principles as “the equality of nations” and non-interference into the internal affairs of other countries. Burnham stated that the U.S. must let the world know that it would bestow its favors exclusively on its friends; and make clear that it was willing to use force to uphold its interests. Above all, the new America would have to assume the task of defending the World Island’s Coastlands and Japan (a potential U.S. offshore ‘outpost’) to prevent the Soviets from mastering the whole of Eurasia. Once it had taken these steps, the new global empire could then bend its efforts toward overthrowing communist rule in countries outside the USSR’s 1940 borders.

Burnham thus concluded that a defensive policy would not suffice. The enemy had to be toppled rather than simply held at bay. For that to occur, an ‘offensive policy’ was necessary. First an “American empire” exercising “decisive world control” and irresistible influence would have to be established so that politically the non-communist world would act as one. The chief step to this end, a step that would “instantaneously transform the whole of world politics” would be the formation by the United States, Britain and the British Dominions of a full-fledged political union, complete common citizenship. Burnham noted that this union would not be easy and that “forceps” might have to be used to achieve its birth.

Next, the Continental European nations not under communist rule would have to join in a ‘European Federation.’ (aka a League of Nations). If these countries balked once again, pressure would have to be applied, though a promise of economic aid might bring them around.

After this consolidation of Europe, Bunrham predicted that the next phase would be an alliance of the Anglo-American combine and the European Federation. In this new form, the West, now deep in its “Time of Trouble” would become a Toynbean “Universal State” with the United States in the role of the peripheral, semi-barbarian, unifying power. But the offensive policy would not stop at the West’s frontiers, for political and economic concessions might induce non-Western nations to act with the West against communism. This is almost verbatim to what Bertrand Russell was calling for; America to become an imperialistic force at the helm of a world empire. This vision was the continuation of the League of Nations.[15]

So much for Burnham’s so-called staunch anti-imperialism…

References:

[1] McGrory, Mary. (Feb. 19, 1950) Reading And Writing. The Washington Post.

[2] The Machiavellians were very Dewey-esque in their scientific outlook, see Appendix II of my book “The Empire on Which the Black Sun Never Set”.

[3] Kelly, Daniel. (2002) James Burnham and the Struggle for the World: A Life. ISI Books Wilmington, Delaware, pg. 107.

[4] Burnham to Markmann, March 30, 1972, Box 5; Burnham, The Machiavellians, preface to the Regnery-Gateway ed., viii. See also Burnham to Norkela, November 19, 1971, , Box 2.

[5] Zeev Sternhell, Mario Sznajder, Maia Ashéri. The Birth of Fascist Ideology: From Cultural Rebellion to Political Revolution. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1994.

[6] Ibid, pg. 90.

[7] Ibid pg. 93.

[8] Eatwell, Roger; Anthony Wright (1999). Contemporary Political Ideologies. London: Continuum. pp. 38–39.

[9] Di Scala, Spencer M.; Gentile, Emilio, eds. (2016). Mussolini 1883–1915: Triumph and Transformation of a Revolutionary Socialist. USA: Palgrave Macmillan

[10] For more on this story refer to my paper How To Conquer Tyranny and Avoid Tragedy: A Lesson on Defeating Systems of Empire. https://cynthiachung.substack.com/p/how-to-conquer-tyranny-and-avoid-a9e.

[11] Roosevelt would pass away just two weeks before the first United Nations conference that would establish its function, which allowed for its hijacking by the pro-League of Nations planners. Recall Chapter 2.

[12] Kelly, Daniel. (2002) James Burnham and the Struggle for the World: A Life. ISI Books Wilmington, Delaware, pg. 121.

[13] Kelly, Daniel. (2002) James Burnham and the Struggle for the World: A Life. ISI Books Wilmington, Delaware, pg. 130.

[14] RAND was also working hard for this exact argument, for more on this story you can refer to my series on RAND In Search of Monsters to Destroy: The Manufacturing of a Cold War. https://cynthiachung.substack.com/p/in-search-of-monsters-to-destroy.

[15] Recall Chapters 2 & 3.