Should the US Remain Responsible for European Security?

This is the question Donald Trump brought to the forefront when he started asking why the US was paying the lion’s share for European security and demanding that members of NATO foot the bill, with at least 2 percent of their GNP. It remains pertinent because the present situation can only exist if the US has the capability to project itself in any direction it wants, when it wants, and whenever it does that this assertion becomes increasingly less credible.

Parties on the same side of a global argument do need to help each other, and NATO provides a structure within which to do that. However, the present arrangement creates a power imbalance which does neither side any good, and is more likely to generate disunity in the face of enemies real and imagined than an effective response to threats.

The swamp didn’t like that….

Until now Europe has been double dipping. The US has subsidised its defence bill and Russia has provided cheap energy. However, this has happened mostly by default, and by allowing the individual European states to be a proxy for the real owner of NATO—the United States.

Europe’s over-dependence on the United States for its security has given the US a de facto veto on the direction of European defence. Since the 1990s, the United States has typically, according to the independent views of American Progress, a US think tank, “used its effective veto power to block the defence ambitions of the European Union, thus not allowing Europe to be able to stand alone in its true defence needs.”

But the fact that Ukraine is not going according to America’s plan opens up a new discussion of what should be the role of NATO in the light of legitimate European Security needs, and even what needs can be called legitimate. With the exception of Poland and Romania, few NATO countries are willing to buy in on instructions from abroad, as if NATO was not already facing real structural problems.

Europe is not what it was. Over the past 30 years, since the proffered end of the Cold War, it has changed dramatically, and particularly in its collective and individual mindsets. It has been living in its own bubble and been only too willing to let others decide its fate.

It is clear that US policy towards European security does not currently reflect Europe’s transformation, and has actually jeopardized its energy security and business model, which is based on the production of high-value products subsidised with cheap Russian energy and imported foreign labour.

If you want to know what NATO is in actuality and what are its real ambitions, look at who is paying for it. The principle enshrined in Article 5 of the Treaty commits them to protecting each other against attack, but at times when they are not under threat, this is more of a stick than a carrot.

NATO claims to be striving to secure a lasting peace in Europe, based on common values of democracy, individual liberty and the rule of law. But this is irrelevant when no one is trying to take those away, and its members are not in agreement as to whom is attacking whom, and what is and what is not a defence organisation.

It’s easy for NATO to beat the war drums when its member states know they don’t have to foot the much of the direct bill. However, it is equally easy for the US to foot the bill, claiming that NATO is doing so, as long as the sons and daughters of European voters, not their own, are going out and getting killed.

It is amusing at this time to read the self-serving comments on NATO sites, including its tweets. Jens Stoltenberg in his annual report describes 2022 as having been a pivotal year for security, and how in a more dangerous and contested world, NATO is standing strong and united, providing unprecedented support to Ukraine.

The above link to the referenced report is portrayed as an opinion, and as such does not reflect the official views of NATO or the United States. However, that is moot for now, as NATO has its own internal problems and does not speak with one voice or represent the “REAL” interests of all members, especially when it comes to supporting a non-NATO member unconditionally.

NATO, is it Friend or Foe?

Henry Kissinger, the former US Secretary of State, summed this up well when he said, “It may be dangerous to be America’s enemy, but to be America’s friend is fatal.” Aside from the claims in Stoltenberg’s annual report, it is clear that things are not going well, with all the money spent, NATO stocks depleted and NATO weakened as a result.

NATO and its birds-of-a-feather have spent vast sums in Ukraine to lose the war. The economies of its main supporters, including Germany and the US, have been brought to a standstill and may never recover to former levels.

At the time of the quote Kissinger was referring to Ngo Dinh Diem, the “American-supported” President of South Vietnam, who was assassinated by his own military after the US removed its support. Nguyen Van Thieu, a later President of South Vietnam, was himself abandoned when the US pulled out of Vietnam a few years later. Will history be repeating itself in Ukraine, or does the Ukrainian president, who campaigned for office based on peace and conflict resolution, have an exit strategy?

Back in the US they would say, “with friends like these, who needs enemies?” Germany knows exactly what this means when it comes to the blowing up of Nordstream 2 at the hands of its staunchest and closest ally, the US, with some help from Norway.

The point is that NATO is no longer a collective security organisation, as there are too many separate agendas amongst its own members. For example, Turkey is no longer a fully-fledged supporting member, as it is too pragmatic to get involved in conflicts artificially created for the benefit of the hegemonic power that sees NATO and its some of its members, such as Romania, Turkey and Poland, and potential members, such as Georgia and Ukraine, merely as useful cannon fodder for some greater good.

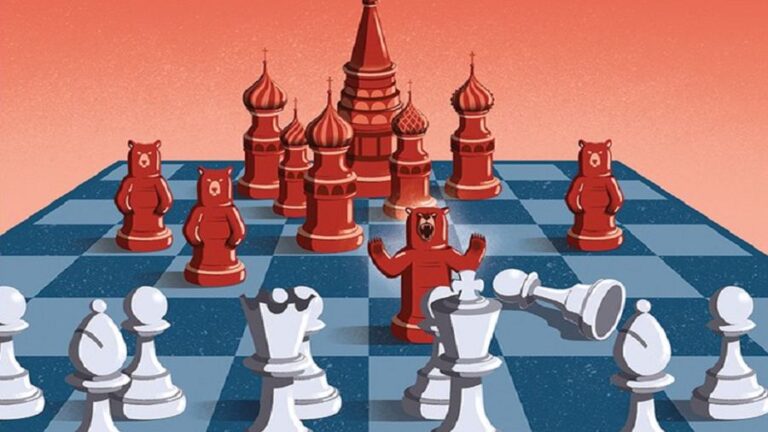

Georgia and Ukraine are case studies of what results from sudden change: it further destabilises an already unstable situation, and prevents the evolution of a security system which would allow real change. Even Poland is skating on thin ice, with few real friends, as the proxies of aggressive US policy in Europe, which is basically “poking the bear.”

Let us not forget the way Poland responded within hours that the missile which landed on the village near its border was “most likely” an errant Ukrainian rocket, as to think otherwise would give the Ukrainians too much credit for an attempted false flag. It came as no surprise that Poland immediately dropped all talk of invoking Article 4, which amounts to nothing more than a request for “consultation.”

Tongue-in-cheek

Any notion that Poland dreams of taking back Western Ukraine is pure imagination. Unlike Russia, which the Poles claim is constantly hankering for lost territory; Poland should have zero interest in recovering impoverished territory in either Ukraine or Belarus.

Whenever you ask Poles whether they would like to get back Grodno or Lviv, they look at you as if you are a mad hatter. They gave up such territory happily in 1945 in return for far more enticing chunks of Germany in the West.

Who would ever want to give up Wroclaw, an amazing and prosperous city, for Grodno, a dump on its border with Belarus? So Poland isn’t going to be persuaded to get more involved than it wishes to, however close it is to Ukraine, by invoking centuries-old territorial disputes.

However, Poles are very conscious of being Poles, and if things go wrong in their own country West Ukraine and Belarus do have special meaning for them because they provide a way out. They may not care about them as former Polish territories, but if Poland is destabilised they might have significance as new ones which will give Poles living space.

Poles know already if something is not done soon, the dominant language in Poland may become Ukrainian. War is encouraging further immigration, for which Poland would want some compensation, as it is one of those countries which claim that free movement of refugees is harming it.

That is the significance of Western Ukraine to Poland – it wants NATO to protect it from invasion by people who were once themselves Polish. They don’t want to make the conflict worse, but will still want something in return for doing nothing, to maintain themselves as a viable state having gone down the road NATO told it to.

Did not the Germans kill about 10 percent of the Polish population, not including its Jews? NATO and the US may indirectly kill and dispossess even more, in the name of common security, in which Poles see themselves as the only ones making the sacrifices.

Joining the Primary Club

US claims that Europe should pay more for its own defence also ring hollow in the ears of prospective members. Some, like Georgia, have tried to bleed itself into NATO, only to find that the negative consequences of doing so outweigh the practical support they receive in return.

Hopefully Georgia does not go down the same path as Ukraine did in 2014. Tbilisi has been in the news over a foreign agent registration law which the Georgian parliament wanted to pass, but the NGOs, NED and CIA would not allow.

Foreign agents come in all shapes and sizes, as most countries also have a presence in many others through diplomacy, business, foreign assistance, programmes etcetera. A law requiring people to register as foreign agents, and therefore purveyors of a particular viewpoint representing a particular interest, should be no threat to anyone who takes the Western position that they deal in truth and their enemies deal in propaganda.

But for now, the Government of Georgia has backed down, under threat of sanctions from the EU and the US for trying to adopt the same laws they have, like all the others they were told were prerequisites of European integration. They can see they are the advance front of further attacks, having been enslaved once by previous US offers of friendship.

Things are quiet in Tbilisi for now, but this is not over, as there are still contingency plans by the US and some of its NATO friends to replace the current government. Ukraine has ended up the way it has because it largely replaced Georgia as the regional CIA dirty tricks capital, so Georgia is the obvious place to run to if it can again be run by compliant crooks pretending to be Western reformers.

Poland should also remember its own history, with the West going to war over it when Germany invaded, and then the allies sacrificing it to the USSR for a decades-long occupation after it had been on the winning side.

It had been predicted that the stick to poke the Russian Bear would be much sharper should the Democrats win the White House, and small countries always see changes in major ones as potential opportunities for geopolitical advancement at the expense of their neighbours. Poland does not want to be that next stick, as it fears that the West, especially the United States, will again sacrifice its close supporter, a full-fledged member of NATO, for the sake of political expediency when faced with the unpleasant alternatives.

Alarms not sounding

The real question is not if the West and the US be jointly responsible for European Security. It is whether Europe is willing to self-reflect and identify its main security risks, and be willing to discuss how to find a way out of a mess created for the benefit of a few, on a level few are willing to accept as possible.

Europeans are keen on the concepts of self-determination, democracy, rule of law and a “rules based” international order. If Europeans were paying for the damaged being inflicted on Ukraine for their sake, they would know the meaning of “if you break it then you pay for it!” But there is also no reason for them to pay for policies which are written in their name, but have little to do with their interests.

As Andrew Korybko so accurately writes, in terms of the demise of American unipolarity, “American officials frame their country’s foreign policy in flowery language alleging that it’s formulated in pursuit of defending “democracy”, “human rights”, and the so-called “rules-based order”, but it’s really driven by the desperate desire to delay its declining unipolar hegemony over international relations.”