India is Holding Back the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and BRICS

Yesterday, Chinese President Xi Jinping addressed the 13th meeting of Security Council Secretaries of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) in Beijing. During the meeting, President Xi stressed the importance of enhanced cooperation between SCO members in the fight against the “three evil forces” of extremism, separatism and terrorism. As one of the international security bodies which covers the largest geographic space, the SCO holds the potential to be a far more meaningful security organisation than either NATO or CSTO. Founded in 1996 by China, Russia, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. The group has since expanded to include Uzbekistan which joined in 2001 and more recently, south Asian rivals India and Pakistan who both joined in 2017.

But while the presence of both India and Pakistan in a collective security body was an ideal situation from the perspective of turning a decades long cold and sometimes hot war between New Delhi and Islamabad into a win-win cooperative situation, such hopes have thus far been relegated to theory rather than practice.

In spite of tremendous potential to create a pan-Asian security bloc that has the potential to grow further in south east Asia and into Europe, the SCO remains stymied by major internal rifts for which India is responsible. Far from seeking to single India out, New Delhi is the consistent outlier in major policy areas that make a united SCO position very difficult. In this sense, India has singled itself out within the framework of the SCO.

While Russia, China and Pakistan have an increasingly unified position on the need to end the current conflict in Afghanistan through an all-parties peace process which would attempt to unite various ethno-political factions in the country into a single coalition government, India is now the Asia cover for the US policy of sowing long-term division along ethno-political lines in Afghanistan.

Likewise, when it comes to embracing One Belt–One Road as a means to create peace through prosperity, India is also the odd man out in the SCO. Because of these two factors, the SCO has gone from being “the” organisation that was going to end hostility between Pakistan and India, to an organisation where all the other members are now essentially getting a first hand taste of Indian geopolitical obstructionism which de-facto increases sympathy for Pakistan’s position on both Afghanistan and One Belt–One Road.

But the SCO is not unique in experiencing de-facto deadlock over issues which require intense cooperation. The BRICS group of nations which includes Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa has also been weakened by Indian obstructionism. The core of the BRICS has always been Russia and China and it is from this close trading, diplomatic and security partnership that the group of rapidly developing nations of the wider global ‘east and south’ was able to congeal. In spite of political turmoil involving the jailing of staunchly pro-BRICS former Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and the highly controversial impeachment of former President Dilma Rousseff, Brazil remains an important component of the group as Latin America’s largest nation. Brazil’s geographic distance from the ‘Eurasia-African’ core of the BRICS has always been obvious but this has never been considered detrimental to the overall health of the BRICS. Due to China’s major investments throughout Africa, including in South Africa, Pretoria’s presence in the group is necessarily positive as it unites the continent most hungry for fresh injections of multi-polar investment with China, the country best place to deliver such investment.

But when it comes to projects ranging from a BRICS currency basket, to a BRICS-wide free trading area or even a BRICS cryptocurrency, it is again India which due to its desire to engage in a zero-sum rivalry with the far more economically powerful China, that is holding such projects back. While some observers blame Brazil’s new right leaning President Michel Temer for apparent lethargy in the BRICS, it is not Brazil that is playing a constantly obstructionist role in the face of new proposals, this remains India, just as is the case in the SCO. Even under Temer, the worst that can be said about Brazil is that the country is taking a “live and let live” approach to the BRICS, but certainly not an obstructionist role.

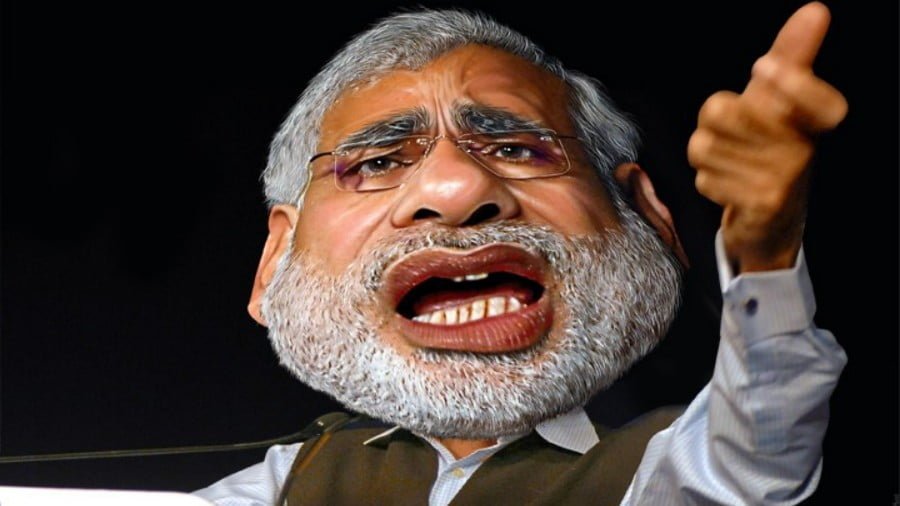

In respect of finding a solution for the problems faced by the BRICS and SCO regarding India’s inability to see eye-to-eye with China and others, the key is not to expel India from either bloc but to expand both organisations so as to emphasise the fact that India is outnumbered among the leading developing nations of Asia, Africa and Latin America. The SCO should expand as rapidly as possible in south east Asia with The Philippines under President Duterte being a prime example of a country that is profoundly increasing its security ties with both China and Russia. There is also no reason why Iran, Belarus and even Turkey cannot be members of the SCO. As the SCO is not a military alliance in the way that NATO is, Turkey would not be under immediate obligations to refrain from participation in the SCO due to its sustained but increasingly peripheral membership of NATO. Later, if countries including Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, Maldives, Sri Lanka, Sudan and Vietnam joined, it could not only provide a wider framework for international security among rapidly developing Asian nations, but it could also demonstrate that between India and Vietnam, Hanoi’s Sinosceptic leaders are nevertheless far more pragmatic than the outright Sinophobic leadership of Indian Premier Modi.

On the economic side of things, the BRICS should expand in order to transform itself into the go-to body for developing nations to receive investment and loans from outside of the western dollar driven financial system. The so-called BRICS+ format has already seen countries from around the world participate as observers in BRICS meetings and/or express a desire to join the group. This includes Mexico, Indonesia, Egypt, Syria, Bangladesh, Turkey, Sudan and Nigeria. There is no reason why due to the already informal nature of many BRICS discussions that these countries should not be able to immediately participate as full members of the group.

The combination of a gradually expanding SCO and a rapid expansion of the more informal BRICS group would not only make both groups more representative and effective for their respective members, but it would also show that India’s games of obstructing anything China thinks is positive, are ultimately out of sync with the rest of the developing world which has acknowledged that in the 21st century, all multipolar roads eventually lead to China – especially in respect of the roads of the wider developing world.

This there is no need to do anything remotely punitive to India. It is simply a matter of showing India which way the multipolar winds are blowing all the while allowing countries that would happily cooperate with fellow BRICS and SCO members to have a seat at the table that India has failed to take advantage of.