The Coronavirus and China-U.S. Relations

One of the unavoidable consequences of political analysis is an out-of-the-blue event that upends apparent trends. For both the United States and China, that event is the coronavirus pandemic, which emerged as both governments were celebrating a trade deal and yet also clashing on other issues. The response to the pandemic in both capitals has been similar, framed by autocratic governing styles and serious mistakes in judgment that have undermined public trust. Sino-U.S. relations have also suffered at a time when a global humanitarian crisis might be one vehicle to revitalize engagement.

Both the Chinese and U.S. governments were initially unwilling to face scientific facts, were late in responding to people’s needs, and tended to blame others. Narrow political considerations dictated their initial blindness to reality and a cover-up of vital information. Neither system is a model of preemptive action in a pandemic.

But there are at least four important differences between Donald Trump’s leadership and Xi Jinping’s. First, whereas Xi recognized the scope of the crisis within a month and took radical steps to lock down the Wuhan area, Trump, during January and February, failed to act on reports from health experts and intelligence officials, including ignoring a pandemic “playbook” put together by Obama’s emergency preparedness team. Trump’s focus has been on the economy—falling production, unemployment, and a stock market crash—and not on public health, as suggested by his comment that coronavirus fatalities were small compared with those caused by the flu and auto accidents. “WE CANNOT LET THE CURE BE WORSE THAN THE PROBLEM ITSELF,” Trump tweeted on March 22—the unacceptable “cure” being shutting the country down to prevent out-of-control infections. By the end of March, infections surpassed 120,000, and Trump’s top two advisers on COVID-19 estimated that there would eventually be between 100,000 and 200,000 deaths.

Second, Trump didn’t use all the tools at his disposal to contain the virus. He took far too long to activate National Guard units and the Army Corps of Engineers. He initially resisted pressure to use his power under the 1950 Defense Production Act to order industries to produce critical equipment, such as ventilators, leaving it to states to work out deals with private industry while also competing with each other. His appointees in the bureaucracies responsible for public health were slow to grasp the enormity of the virus and gird for mass testing.

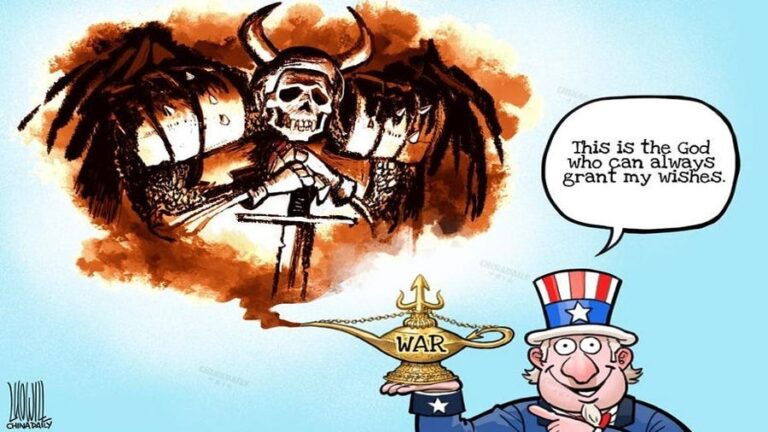

Third, some Chinese media and officials hold the United States responsible for the coronavirus, but not Xi (at least publicly). But Trump, some of his top advisers, and the right-wing media scapegoat China, employing racist language to boot. Trump has wondered aloud why China took “three or four months” to let the United States know about the virus, when in fact China identified the problem late in December 2019 and then shared the genetic code with U.S. scientists. He is among those who insist on calling the virus “Chinese” or “Wuhan”—a characterization that legitimizes growing anti-Chinese resentment around the United States.

Fourth, China has become the leading international donor of supplies and expertise to countries where the COVID-19 infection rate is especially high, including Italy, German, Spain, the United States. Of course, these donations have propaganda value and are meant in part to mask the mistakes at Wuhan. But China has emerged from the virus and is providing foreign aid to fight it, in comparison to the United States, which has shortages of essential equipment and no national strategy for obtaining it. This contrast speaks volumes about how world leadership is changing.

Unfortunately, one other leadership difference is that China is using the COVID-19 crisis to increase surveillance. To better identify carriers of the virus, all Chinese must register by cell phone for an app that separates the healthiest from the most vulnerable. But the data also gives police authorities another tool to locate and monitor individuals. This is occurring as large numbers of Internet police, who belong to a little-known cybersecurity force within the public security bureau, are searching for dissidents. Some prominent human rights advocates who have criticized Xi’s handling of the virus have been jailed, including law professor Xu Zhangrun, book publisher Gui Minhai, legal activist Xu Zhiyong, and real estate mogul Ren Zhiqiang.

The Backward Drift of Relations

Until the onset of COVID-19, the U.S. view of China had been dictated by trade talks. Widespread violations of human rights norms in China—the mass incarceration of Muslims in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, the attempts to crack down on pro-democracy demonstrations in Hong Kong, and the jailing of regime critics—got only mild and inconsistent notice from the Trump administration. When the virus hit Wuhan, Trump was advised by cabinet members and public health experts to ban travelers from China. He hesitated out of concern about a ban’s impact on trade talks and the U.S. economy. The ban went into effect at the end of January 2020, but Trump praised Xi’s handling of the virus on several occasions. He said at that time, for example, that China was “working very hard” to stop it and, throughout February, that China was showing “great discipline” under Xi’s “extremely capable” leadership. These remarks were made at the very time that Trump was ignoring warnings from within the administration of an impending pandemic.

Now the talk in Washington is about economic and technological decoupling with China. But the decoupling is not over human rights issues, which have never interested the Trump administration. Cybersecurity and a pandemic, however, are of great interest, since both affect U.S. industry and trade, and Trump’s chances of reelection. Casting China as a security threat is an easy way to garner support on Capitol Hill these days. A new bipartisan consensus on China has emerged, with some liberals joining with conservatives to argue the need to confront China’s across-the-board efforts to influence American opinion.

COVID-19 has created a unique opportunity for cooperation that is being squandered by xenophobic outbursts. At a time of an international public health crisis, we need more, not less, interaction with China. Cutting back people-to-people and other exchanges, closing down Confucius Institutes, imposing immigration and visa restrictions, limiting technology transfers, reclassifying Chinese media offices in the United States as foreign operations, and putting Chinese nationals and Americans of Chinese heritage who work in U.S. laboratories and universities automatically under suspicion is nothing less than a new Red Scare. Yes, China has engaged in cyber hacking, stolen technical secrets, and spied on sensitive US installations. Yes, in a few cases Confucius Institutes on American campuses have been kept from putting on programs on Taiwan and Tibet. And yes, some American scientists have accepted research positions in China that are more attractive, in money and equipment, than anything available at their home universities. But there is no evidence that these events are part of some Chinese master plan to compromise U.S. national security. They should not become a pretext for making unfounded accusations or threatening universities with loss of federal funds.

Is China really “the central threat of our times,” as Pompeo said in London in January 2020? The Trump administration evidently thinks so. But politically motivated sanctions that hold up China as an enemy foreclose opportunities for cooperation and encourage retaliation, which Beijing has conducted against the United States and other foreign journalists and NGOs since the trade war began. Sanctions and other negative incentives also fail to project the best of American society and democratic values—not to mention doing nothing to alleviate China’s repressive policies. Policy-specific criticism of and competition with China, on the other hand, are certainly in order—for instance, on human rights violations, Asia-Pacific trade and investments, and technology advances such as 5G networks. Also appropriate are actions against unfair Chinese practices, such as harassing journalists, receiving low-interest World Bank loans, and ignoring foreign investors’ intellectual property rights. But “reciprocity” and fairness should not be confused with containment.

But Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s statement last year – that Beijing poses “a new kind of challenge; an authoritarian regime that’s integrated economically into the West in ways that the Soviet Union never was” – ignores the fond wish of U.S. leaders for many years that China embrace globalization. Also forgotten is that competition is supposed to be the American way—until now, when China is outcompeting the United States. Vice President Mike Pence has twice given major speeches on China policy, each time sounding like a cold warrior disappointed in China for failing to liberalize and determined that China’s “provocations” will be answered forcefully. “So far,” said Pence, “it appears the Chinese Communist Party continues to resist a true opening or a convergence with global norms,” by which he clearly meant compliance with U.S. policy preferences. Neither he nor Pompeo had anything to say about how U.S. policies, notably the trade war, have contributed not only to tensions with China but also to developments elsewhere contrary to US interests, such as deteriorating U.S. relations with South Korea and increased Russia-China military cooperation.

Competitive Coexistence

Positive relations with China are of far greater importance to U.S. national interests than are relations with Russia. That doesn’t mean that Washington should neglect opportunities for engaging Moscow. Rather, finding common ground with China is essential to maintaining a peaceful international order on such issues as disease control, terrorism, climate change, the international economy, energy, maritime rules of the road, nuclear and conventional weapons proliferation, and aid to developing countries. These are areas where U.S.-China cooperation is crucial to Asia’s and the world’s well-being. Red scares only make the friction worse. Evan Osnos writes that “uneasy coexistence” is the likely future of US-China relations. In policy terms, U.S. relations with China ought to rest on competitive coexistence.

There are at least two fundamental obstacles to finding common ground. The first is how to bridge the great divide between a newly empowered China and a United States used to being number one. The challenge here comes down to different notions about the international order—what is its essential aspect, who should define it, and how should it be maintained. For the United States, the international order is rules-based, it is defined by the post-World War II institutions that the United States led in creating, and it should be led first and foremost by Washington. China’s role should be that of “responsible stakeholder,” as Robert Zoellick famously said in 2005. For China, on the other hand, the international order is multipolar, demanding creation of a “new kind of great power relationship” in which China’s role is that of a “responsible great power.” These differences over global responsibility and rule-making will persist for some time. Although they need not inhibit finding common ground, they will be a constant source of friction unless directly addressed.

The second challenge in U.S.-China engagement is that both leaderships share a dangerous insecurity. They both operate out of fear. China worries about popular demands for democratic reforms, social protest, an independent media, and economic downturns that create instability. The Trump administration fears democracy, avoids accountability, is contemptuous of the rule of law, and is plagued by corruption and constant internal friction. It faces a population deeply divided over national priorities, culture, race relations, and even the coronavirus, with Democrats far more fearful than Republicans about its effects on health. Both leaderships fear the foreigner, whether that takes the form of reducing immigration or weeding out non-native influences.

Significant portions of both the Chinese and American populations are angry and lacking confidence in their leaders. Political leaderships thus confronted, and convinced of their righteousness, may lash out in a variety of directions. Trade wars, tit-for-tat responses in diplomatic disputes, and military confrontations are all possible. Promoting conspiracy theories and demonizing the other are to be expected. The times call for mutual restraint, recognizing that the latest pandemic, like climate change and mass migrations, can only be effectively dealt with through international collaboration.

By Mel Gurtov

Source: In the Human Interest