After Australian Report It’s Time for Serious US War Crimes Probes

Australia had to reveal heinous crimes its troops committed in Afghanistan, even after it prosecuted a whistleblower and raided a TV station. It’s time for the U.S. to launch serious investigations of its own conduct in war, writes Joe Lauria.

The report of a four-year Australian government investigation into alleged war crimes by the country’s special forces in Afghanistan was published on Thursday, revealing unspeakable atrocities against civilians.

The report details how at least 25 members of Australia’s Special Air Services (SAS) were involved in 39 murders of civilians. The report’s description on page 120 of just one incident suffices to describe the nature of these crimes:

“Special Forces would then cordon off a whole village, taking men and boys to guesthouses, which are typically on the edge of a village. There they would be tied up and tortured by Special Forces, sometimes for days. When the Special Forces left, the men and boys would be found dead: shot in the head or blindfolded and with throats slit.

Cover-ups. A specific incident described to Dr Crompvoets involved an incident where members from the ‘SASR’ were driving along a road and saw two 14-year-old boys whom they decided might be Taliban sympathisers. They stopped, searched the boys and slit their throats. The rest of the Troop then had to ‘clean up the mess’, which involved bagging the bodies and throwing them into a nearby river…”

Learning to Kill

The report on page 29 describes a practice known as “blooding”:

“…the Inquiry has found that there is credible information that junior soldiers were required by their patrol commanders to shoot a prisoner, in order to achieve the soldier’s first kill, in a practice that was known as ‘blooding’. This would happen after the target compound had been secured, and local nationals had been secured as ‘persons under control’. Typically, the patrol commander would take a person under control and the junior member, who would then be directed to kill the person under control. ‘Throwdowns’ would be placed with the body, and a ‘cover story’ was created for the purposes of operational reporting and to deflect scrutiny. This was reinforced with a code of silence.”

Nineteen of the 25 soldiers involved face criminal prosecution. Their unit has been disbanded. As many as 3,000 soldiers will have their medals stripped and special forces in future will wear body cameras.

These are the kinds of crimes that show an unbroken link to colonial barbarity dating back to the 19th Century, when Western soldiers, jacked up to kill their “inferiors” then as now, are unleashed on innocent populations in developing countries.

Prosecution and a Raid

The Australian government was aware of such allegations when an Army lawyer in Afghanistan named Maj. David McBride came forward as a whistleblower. He recounted what he had witnessed up the chain of command and was ignored. He then gave his story and documents to the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. ABC reported the “Afghan Files” in July 2017.

“The documents also provide fresh details of some notorious incidents, including the severing of the hands of dead Taliban fighters by Australian troops,” the ABC reported, much like the photo in the tweet above from the Belgian Congo.

For his efforts, McBride was arrested and is being prosecuted for divulging classified documents (marked Australian Eyes Only). He faces life in prison. For its efforts, the ABC’s offices in Sydney were raided by Australian Federal Police (AFP) and copies of files were taken from newsroom computers.

The raid took place less than two months after the April 2019 London arrest of the Australian Julian Assange, WikiLeaks publisher, who had himself revealed war crimes in Afghanistan and Iraq. An ABC journalist, Dan Oakes, who was facing prosecution for publishing classified information (just like Assange), had his charges dropped on Oct. 15, just a month before the government report confirmed McBride’s story and Oakes’ reporting.

I wrote at the time of the ABC raid:

“While there is no direct connection between Assange’s arrest and indictment for possessing and disseminating classified material and these subsequent police actions, a Western taboo on arresting or prosecuting the press for its work has clearly been weakened. One must ask why Australian police acted on a broadcast produced in 2017 and an article published in April only after Assange’s arrest and prosecution.”

The prosecution of McBride so far continues. It would be an even bigger scandal than his arrest, if his charges aren’t dropped too.

It’s Your Turn U.S.

This could be a watershed moment for Australia, which has been shaken by the government’s report. It might rethink its military policy and perhaps its knee-jerk obedience to an order from the United States to join its wars.

Australia was only in Afghanistan because of the U.S. For his devotion to Washington in sending Australian troops far away to Afghanistan in 2005, former Prime Minister John Howard was rewarded with the Presidential Medal of Freedom by George W. Bush, who started the Afghan War in 2001.

What Australia has now finally done should be a lesson for its Five Eyes senior partner. As it is, the United States has a very sparse record of prosecuting its own war crimes.

While there were at least 10 known war crimes during the U.S. Civil War, (especially Sherman’s scorched earth drive to the sea) only four men, all confederates, were prosecuted after the war ended. During the war against Native Americans, the U.S. government authorized raids, which often led to massacres. Rather than prosecuting, the government rewarded Americans for killing indigenous people.

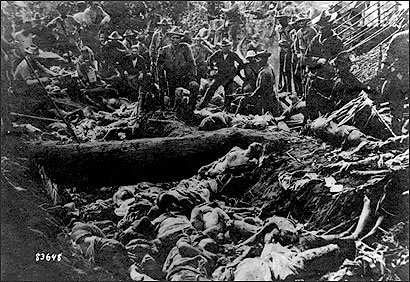

In the U.S. colonial war in the Philippines after the 1898 war against Spain, Brigadier General Jacob H. Smith was court-martialed and forced to retire after he told the commanding officer at Samar: “I want no prisoners. I wish you to kill and burn, the more you kill and burn the better it will please me. I want all persons killed who are capable of bearing arms in actual hostilities against the United States.”

A widespread massacre of civilians followed. Filipino historians say up to 50,000 people were slaughtered. Mark Twain, who opposed the U.S. war in the Philippines, wrote: “In what way was it a battle? It has no resemblance to a battle. We cleaned up our four days’ work and made it complete by butchering these helpless people.” It was not the only U.S. massacre in that war.

The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 followed the Geneva Convention of 1864 as the first international war crimes laws. All sides in the First World War, including the U.S., used poison gas, which was a violation of the Hague Conventions, but no one was prosecuted for it.

According to History.com, “Future president Harry S. Truman was the captain of a U.S. field artillery unit that fired poison gas against the Germans in 1918.” It would not be the last time Truman was involved with unconventional weapons.

His dropping of two atomic bombs on civilians in Japan, opposed by top U.S. generals, is likely the biggest war crime in history. It was celebrated and not punished. There is a long list of documented U.S. and allied war crimes and crimes against humanity in the Second World War but the trials were reserved for defeated German and Japanese war criminals.

A U.S. war crime during the Korean conflict was covered up for nearly 50 years, before the Associated Press revealed it in 1999. U.S. soldiers massacred refugees at No Gun Ri in 1950. No one was ever charged.

In the Vietnam War, massacres of civilians were routine, according to Nick Turse, author of Kill Anything That Moves. But there were few prosecutions of U.S. soldiers. Only 203 U.S. military personnel were charged, 57 were court-martialed and 23 were convicted, not including the most well known case of My Lai.

The My Lai incident was revealed to the public in Nov. 1969 through the reporting of investigative journalist Seymour Hersh. An army veteran whistleblower, Ronald Ridenhour, had first written in early 1969 to the White House, the Pentagon, the State Department and members of Congress revealing credible details about the massacre. It lead to a military investigation.

The probe found that U.S. Army soldiers had killed 504 unarmed people on March 16, 1968 in the village of My Lai, including men, women and children. Some women were gang-raped by the soldiers. The military investigation led to charges against 26 soldiers. Just one, Lieutenant William Calley Jr., a C Company platoon leader, was convicted. He was found guilty of the premeditated murder of 109 villagers. (Given a life sentence, he ultimately served only three and a half years under house arrest.).

But Calley’s conviction was largely covered up by the military until Hersh broke the story. It was Hersh again, more than 30 years later, who would break the story of torture at the U.S.-run prison in Abu Ghraib. When the news media makes a splash with evidence of a U.S. war crime, the government is sometimes forced to act. Such was the case with the prison torture as the public was outraged, especially by the photographs.

U.S. soldiers were acting in a post 9/11 environment in which U.S. leaders openly supported torture and White House lawyers and the then U.S. Attorney General Alberto Gonzales argued that detainees were “unlawful combatants” and not protected as prisoners of war by the Geneva Conventions, a series of war crimes conventions from 1864 to 1949.

U.S. war crimes were becoming normalized legally, and, except for old school reporters like Hersh, not investigated by the news media. It has amounted to a sense of impunity for U.S. leaders to commit whatever crimes they need to commit during war. Few people learn about them. As Harold Pinter said in his 2005 Nobel Prize acceptance speech:

“My contention here is that the US crimes in the same period [the Cold War] have only been superficially recorded, let alone documented, let alone acknowledged, let alone recognised as crimes at all. … the United States’ actions throughout the world made it clear that it had concluded it had carte blanche to do what it liked….It never happened. Nothing ever happened. Even while it was happening it wasn’t happening. It didn’t matter. It was of no interest. The crimes of the United States have been systematic, constant, vicious, remorseless, but very few people have actually talked about them. You have to hand it to America. It has exercised a quite clinical manipulation of power worldwide while masquerading as a force for universal good. It’s a brilliant, even witty, highly successful act of hypnosis.”

The American people did learn about Abu Ghraib, however, and an investigation had to be launched. Then Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld was hauled before the Senate and House Armed Services Committees and said: “These events occurred on my watch…as Secretary of Defense, I am accountable for them and I take full responsibility…..there are other photos — many other photos — that depict incidents of physical violence towards prisoners, acts that can only be described as blatantly sadistic, cruel, and inhuman.”

George W. Bush didn’t apologized, but expressed remorse “for the humiliation suffered” by Iraqi prisoners. But the investigation only convicted seven low level soldiers in the prison. Brig. Gen. Janis Karpinski, who oversaw the prison, was merely demoted to colonel. When President Barack Obama came into office, he refused to investigate U.S. officials for torture, preferring to not “look back.” In that way he added to American impunity.

In Afghanistan, the U.S. convicted one soldier for murder, put another on trial and demoted a third who was acquitted of murder. But President Donald Trump pardoned the first two and restored the rank of the third, perhaps making him an accessory to a crime after the fact. When the International Criminal Court announced in March that it would launch an investigation into alleged U.S. crimes in Afghanistan, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo reacted by threatening ICC officials with sanctions if they came to the United States.

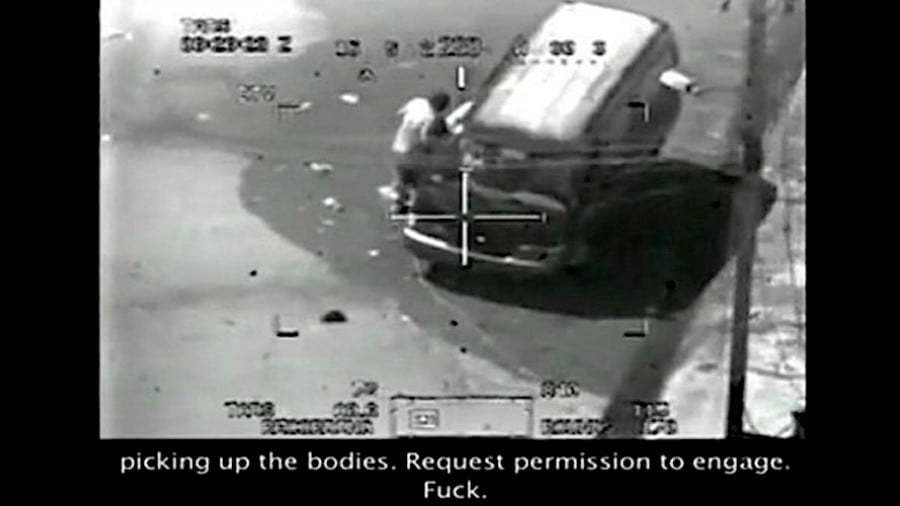

Unlike the reaction to Abu Ghraib, another revelation of prima facia evidence of a U.S. war crime in Iraq has been virtually ignored: WikiLeaks Collateral Murder video.

Despite initial interest when it was released, nothing happened, as Pinter would say. Instead of prosecuting the soldiers involved in the Collateral Murder massacre, the U.S. government has arrested and put on trial Assange, the journalist who exposed it and imprisoned his source, Chelsea Manning.

Having come clean on its own war crimes, Australia should at long last assert its sovereignty and tell the United States to send its citizen home. To not do so would be to make a mockery of its report revealing its own war crimes.