The Improvement Of Pakistani-American Ties: Imperatives, Variables, And Consequences

The success of the new coalition authorities’ plan to improve ties with the US is dependent on resolving interconnected domestic-international dilemmas and importantly doing so before the narrow window of opportunity closes ahead of the US’ fall midterm elections.

The recent change of government in Pakistan, which former Prime Minister Imran Khan claimed was a US-orchestrated regime change carried out as punishment for his independent foreign policy but is described by the new coalition authorities as a constitutional and purely domestic process (the assessment of which is shared by The Establishment), has generated heated discussion about the future of Pakistani-American ties. The purpose of this piece is to analyze the imperatives, variables, and consequences of improved relations between these traditional partners within the complex domestic and international contexts in which this might happen.

Generally speaking, Pakistan aspires to practice a balanced foreign policy whereby it develops mutually beneficial ties with all Great Powers without this occurring at the expense of any third party. The intent is to preemptively avert any potentially disproportionate dependence on any given partner, both overall and in terms of specific spheres such as the economy, energy, or military-technical cooperation. Former Prime Minister Khan oversaw the practical implementation of this policy, which was enshrined in Pakistan’s first-ever National Security Policy from January that incorporated insight from all of the country’s stakeholders, including The Establishment.

While this multipolar vision made enormous inroads with respect to Pakistan’s rapid rapprochement with Russia (which in turn opened up opportunities across Moscow’s “sphere of influence” in Central Asia), the reaffirmation of its strategic partnership with China (especially through the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, CPEC, which serves as the Belt & Road Initiative’s flagship project), and the international Muslim Community (Ummah, through former Prime Minister Khan’s global campaign against Islamophobia), it didn’t succeed in incorporating an American and/or European Western element to balance out these non-Western achievements.

That wasn’t through any fault of Pakistan’s own nor of its former Prime Minister, but was entirely due to the Biden Administration neglecting its traditional South Asian partner. The reasons for that arrogant approach are many but most observers consider it to have been driven by the US’ desire to continue mistreating Pakistan as a vassal state in spite of its former Prime Minister’s passionate attempts to equalize their relationship by demanding that his country finally be treated with the respect that it’s always deserved. This took the form of sharp rhetoric against the US’ unipolar policies (most famously his refusal to host US bases in the event that he was asked) and his non-Western diversification policies.

US strategists interpreted both well-intended actions as hostile because of the ideological prism through which they formulate their policies: the discredited supremacist belief in so-called “American Exceptionalism”. Whereas the former Trump Administration sought to place geo-economics at the forefront of US policymaking, ergo his dramatic proposal to scale up bilateral trade by 10-20x, its successor returned to that declining unipolar hegemon’s ideological roots. This outlook was radicalized in the face of America’s chaotic evacuation from Afghanistan in August following the Taliban’s swift capture of the country, which compelled the US to make Pakistan the scapegoat for its defeat.

It also deserves mentioning that US President Joe Biden never called former Prime Minister Khan despite the Pakistani leader actively assisting with America’s evacuation efforts, including that which involved the US’ Western civilian allies there. Speculation also abounded within Pakistani society that their country’s economic and financial problems, largely worsened as they were by the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic and their state’s inclusion on the Financial Action Task Force’s (FATF) “grey list”, were part of a US Hybrid War plot to punish it for its independent foreign policy. These perceptions shaped the run-up and immediate aftermath of its controversial change of government this month.

The removal of former Prime Minister Khan, whether one interprets it as being the result of a US-orchestrated regime change or a constitutional and purely domestic process, creates the opportunity for a rapprochement between these traditional partners. Islamabad has desired such for years but was regularly rebuffed by Washington for the earlier explained reasons. New Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif declared in his inauguration speech that he wants to prioritize this vector of his administration’s foreign policy, which was reciprocated by US officials. His country’s reasons for doing so were already discussed but it remains unclear whether the US will agree to this on Pakistan’s terms of respect and equality.

Therein lies the crux of the problem because it’s extremely unlikely that the US will suddenly reverse its ideologically driven policy towards Pakistan aimed at returning it to vassal status simply because its outspoken former leader was just removed. This logical observation, which is consistent with American policy across the decades towards all partners without exception, suggests that Washington will informally require Islamabad to enact some concessions towards the hitherto implementation of its multipolar balancing act that can only be speculated upon at the moment. One possibility, however, is that it’ll request that Pakistan slows down the pace of its rapid rapprochement with Russia.

The reader should be reminded that the Pakistan Stream Gas Pipeline (PSGP) and February 2021’s agreement to build a Pakistan-Afghanistan-Uzbekistan (PAKAFUZ) railway represent multipolar flagship projects. It’s also important to point out that former Prime Minister Khan practiced a policy of principled neutrality towards Russia’s ongoing special military operation in Ukraine whereby Islamabad refused to vote against Moscow at the UN. Furthermore, his trip to the Russian capital in late February sought to clinch other mutually beneficial deals as well such as those concerning the import of agricultural products in order to mitigate the consequences of the impending global economic crisis.

It’s unrealistic to expect the US to reverse decades of policy towards Global South countries like Pakistan and all of a sudden treat that country with the respect that it deserves as an international equal in the eyes of the UN Charter just because its outspoken former Prime Minister was just removed. Whether it concerns Pakistan’s relations with Russia or whatever else one might speculate, there should be no doubt that Washington will require some concession or another in exchange for repairing their troubled relations. It’s of course up to the new coalition authorities to do whatever they believe is in their country’s best interests in consultation with The Establishment, but their hands are objectively tied.

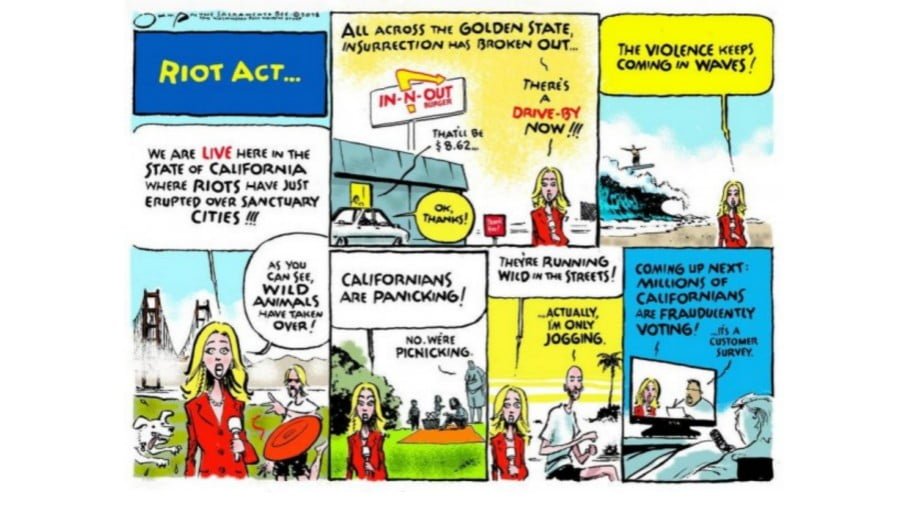

That’s because former Prime Minister Khan’s contentious removal from office unleashed unprecedented socio-political processes that built upon preexisting dissent to suddenly create revolutionary conditions within the country that completely caught its stakeholders by surprise. In this tumultuous and highly fluid domestic political context, the new coalition authorities risk inadvertently provoking nationwide anti-American protests in the event that they visibly compromise on any significant aspect of the prior government’s multipolar and pro-sovereignty policies. Popular opinion among a significant swath of the population is such that they simply wouldn’t accept that happening.

The Biden Administration cannot politically afford to actively cooperate with a country that’s experiencing a surge of anti-American protests ahead of the fall midterm elections since this could be capitalized upon by their Republican opponents to catapult their candidates to power in Congress and thus hamstring the incumbent’s foreign policy across the next 2,5 years in the run-up to the 2024 presidential elections. Considering that Pakistan is slated to hold its next elections in summer 2023 at the latest, it might be the case that the formerly ruling PTI party returns to power – whether in whole or in part – and in turn hamstrings The Establishment’s efforts to repair ties with the US as revenge.

This means that the window for improving bilateral ties is extremely narrow and fraught with immense political risk inside Pakistan itself pending a mutually acceptable resolution of its current crisis between the three primary stakeholders: former Prime Minister Khan’s PTI, the new coalition authorities, and The Establishment. Absent that, the new coalition authorities will struggle to repair ties with the US due to the credible concern that this could further exacerbate the surge of anti-American sentiment that’s sweeping Pakistan in response to the perception among a significant share of the most politically active parts of the population that the new authorities were brought to power by the US.

Should this dilemma be resolved in one way or another, and it remains to be seen how this can be since the two politically competing sides – former Prime Minister Khan’s PTI and The Establishment-supported coalition authorities – currently have polar opposite and seemingly irreconcilable proposals for how to bring this about, then the consequences of the successful implementation of this planned Pakistani-American rapprochement could be enormous and far-reaching. In theory, the Pakistan economy can accelerate its recovery if the Biden Administration dusts off its predecessor’s ambitious geo-economic proposal and meaningfully seeks to implement it through massive investments in that country.

From the perspective of American businesses, Pakistan is the perfect place to invest in since its Chinese-constructed infrastructure (particularly power plants and roads) meets their needs without them having to pay these so-called “entry costs”. Furthermore, the potentially modernized expansion of their existing free trade agreement could turn that country into the regional launching pad for US firms’ engagement with Central & South Asia, the first of which can be achieved by taking advantage of PAKAFUZ’s promised access to that geostrategic landlocked region. This optimistic outcome would be mutually beneficial and also help Pakistan diversify its economy from any potential dependence on China.

American strategists might see another layer of benefit to the success of their planned rapprochement too, particularly in the context of the New Cold War. India’s unwavering commitment to its principled neutrality towards Russia, which is driven by its grand strategic goal of maintaining the balance of influence across Eurasia between those two and China, has created problems in its strategic partnership with the US. America can no longer take that country for granted as its launching pad for expanding its influence across the South Asian region and those adjacent to it. With “Pakistan back in play” after its change of government, the US might return back to its traditional partner out of convenience.

Should that happen, and it of course can’t be known for sure whether or not that outcome will transpire, then it would further solidify the Russian-Indian Strategic Partnership. Not only that, but Pakistan might once again become a bridge between the US and China just like it was in the 1970s, perhaps even working behind the scenes to mediate between them with an aim towards facilitating a potential de-escalation that would work out to everyone’s benefit. That can only happen, however, if Pakistan doesn’t distance itself from China under US pressure as a part of America’s speculative concession demands in exchange for a rapprochement, hence why ties with Russia might suffer instead.

To be clear, it’s in both Russia and Pakistan’s interests to continue building upon the solid basis of their ties that former Prime Minister Khan established, which was reaffirmed by President Putin himself in his congratulatory note to Prime Minister Sharif. Nevertheless, the pro-US school of thought that’s speculated to exist with Pakistan’s Establishment and which might have returned to policymaking prominence following the recent controversial change of government there might sincerely believe that their country’s grand strategic interests are best served by partially compromising on ties with Russia in pursuit of accelerating their hoped-for rapprochement with the US for the explained ends.

Once again, the reader should remember that any visible concessions towards former Prime Minister Khan’s foreign policy – especially with respect to Russia – could provoke massive indignation across society considering the extremely tense domestic political context in which this might happen unless the dilemma between his PTI and The Establishment-backed coalition authorities is resolved in a mutually acceptable way. Furthermore, even the slowing down of Pakistan’s rapid rapprochement with Russia might inadvertently send off the signal to its other partners that the new coalition authorities are indeed at the very least sympathetic to the US in ways that might make others question their independence.

This brings the analysis around to the second dilemma that’s inextricably linked to the domestic one, and that’s the challenge that the new coalition authorities have in disproving the popular perception across the Global South that they were swept into power as part of a US-orchestrated regime change. It’s unimportant in this context what really happened since “perceptions are reality” so to speak and former Prime Minister Khan’s claims resonated across the entire non-West. No matter what the new coalition authorities might say in their defense, the non-Western majority of humanity will look more closely at their actions than their words and react with suspicion if there’s a visible disconnect.

Everyone should hope that Pakistani-American relations can eventually “normalize” to the point where this proud South Asian state is finally treated by the US with the respect that it deserves as that country’s equal in the eyes of international law. Its people can tremendously benefit from large-scale and strategically driven American investments into their economy, as can the country’s multipolar grand strategy in general if this serves to effectively recalibrate its balancing act between Great Powers, especially if it results in Pakistan serving as a bridge between the Chinese and American superpowers in the emerging bi-multipolar world order.

Nevertheless, very serious obstacles still remain in the path of this well-intended plan. The new coalition authorities don’t have the trust of the most politically active segment of the population, which has staged some of Pakistan’s largest-ever rallies against them. The Global South is also suspicious of its foreign policy intentions too considering the contentious circumstances in which they came to power. The success of the new coalition authorities’ plan to improve ties with the US is therefore dependent on resolving this domestic dilemma, its associated international one, and importantly doing so before the narrow window of opportunity closes ahead of the US’ fall midterm elections.

The Republicans’ potential victory could capsize these plans in an instant since that party is considered to be even more pro-Indian than the Democrats. They wouldn’t tolerate the granting of aid or privileged trade relations to a country where US flags might be burned in nationwide anti-American protests inspired by Prime Minister Khan’s interpretation of the events behind his ouster and/or the public’s rage at any perceived concessions towards the US with respect to their pro-sovereignty foreign policy, especially regarding Russia (seeing as how Pakistan’s rapprochement with it was suspected to have triggered the US’ alleged regime change). For that reason, the success of this plan remains uncertain.